KN Magazine: Interviews

Clay Stafford talks with Paul Karasik on “How to Write a Graphic Novel”

Two-time Eisner Award winner Paul Karasik joins Clay Stafford to discuss how to write a graphic novel—how to think visually, collaborate with artists, and translate emotion into panels. A masterclass in visual storytelling from one of comics’ most insightful minds.

Paul Karasik interviewed by Clay Stafford

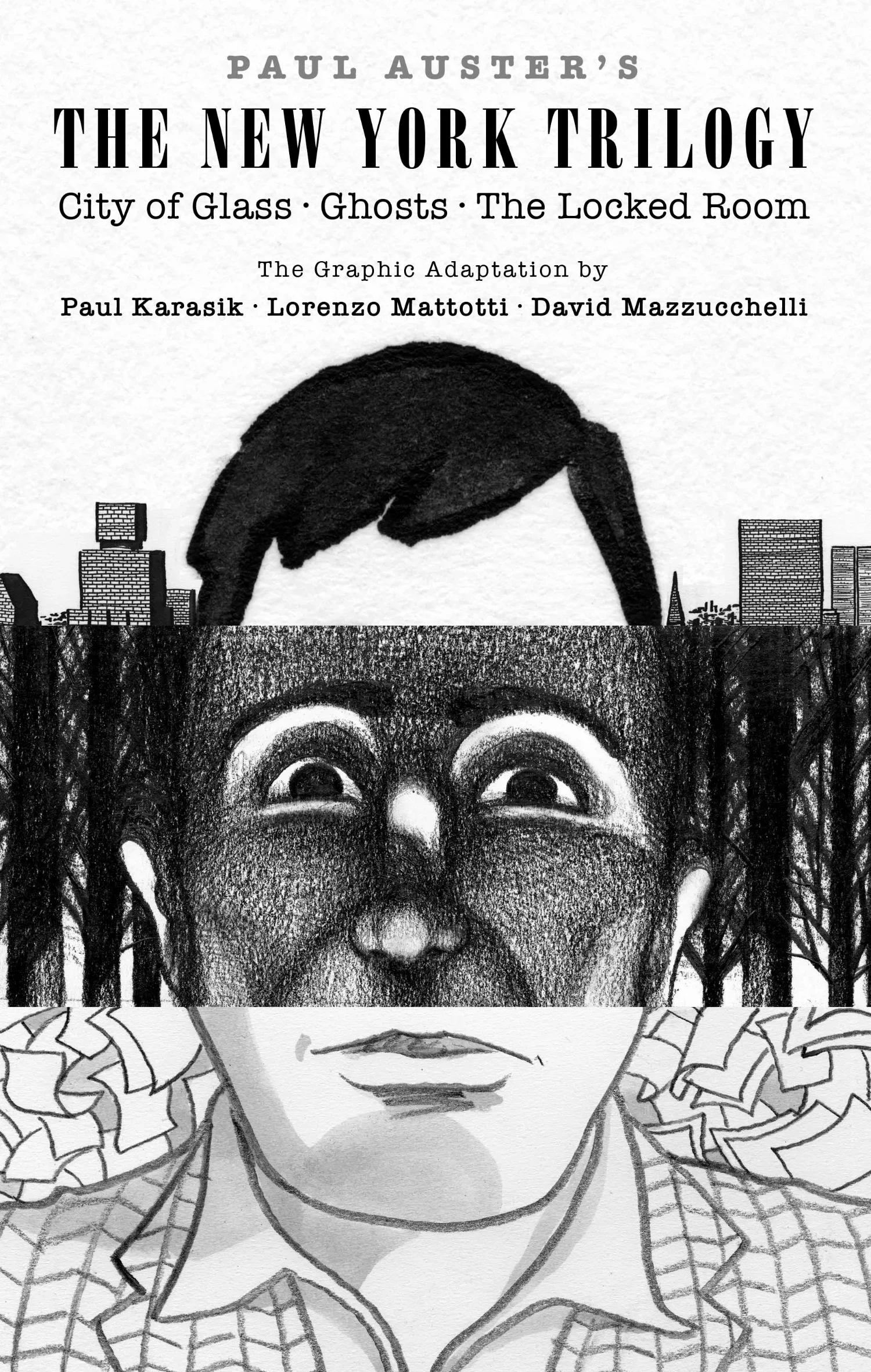

In the world of graphic storytelling, few figures bridge scholarship, craft, and creativity as seamlessly as Paul Karasik. A two-time Eisner Award winner, Karasik’s career has spanned from his early days as Associate Editor at RAW, the influential magazine founded by Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly, to adaptations of literary works that redefined what comics could do. His collaborations include The New York Trilogy, the acclaimed visual deconstruction How to Read Nancy (co-written with Mark Newgarden), and the memoir The Ride Together, written with his sister about growing up alongside their brother with autism.

Karasik is not simply an artist who draws or a writer who scripts. He’s a thinker who dissects how meaning is built through image, rhythm, and restraint. His teaching has influenced a generation of visual storytellers to approach comics as architecture: design, intention, and emotional subtext all working in tandem. In this conversation, I spoke with Paul about how to write a graphic novel: how to think in images, collaborate with artists, structure the visual page, and find the emotional heartbeat that turns panels into story. What follows is a masterclass in how words and pictures meet, and how purpose turns craft into art.

“Paul, let’s say I’ve decided to write a graphic novel, and I don’t know where to start. I’m not trying to sell it or anything; I just want to write it. I’ve heard that you need to think in scenes, not paragraphs. I’m not sure exactly what that means.”

“It’s more like screenwriting. Because it’s a visual medium, you really need to have a clear picture in your head of what everything looks like and how the space is laid out. Draw a little blueprint of what’s happening in any given scene so the characters move consistently through that space. The sofa is always to the left of the dining room table, or whatever. You need to have that visual sense.”

“So, in a way, the writer is the director, and the graphic realization comes from working with an artist, just as the filmic realization comes from working with a cinematographer. Is that a good analogy?”

“Absolutely. That’s a fine analogy. You’re engaging in a collaborative art. You’re working with an artist whom you may not have met yet, so you have to develop a relationship that allows for interpretation. Ideally, you find someone you can continue to work with. Ingmar Bergman is a great director, but Sven Nykvist was his cinematographer. Bergman’s movies always look like Bergman’s movies. You need that same strong sense of what the whole thing will look like and what its emotional core is. What’s the point? There’s the text, and then there’s the subtext. If you’re not addressing the subtext, you might as well be writing ad copy. One of the things I tell my students is that in a graphic novel, you don’t have a lot of space for dialogue. Your first draft can be verbose because you’re figuring out what the character needs to say. But once you know that, it has to be boiled down to ten words or less. You can’t have people going on for three paragraphs, or even three sentences. Two sentences max in a word balloon. There just isn’t that much space, and you don’t need it because the picture is doing the bulk of the work. So, two rules for dialogue: keep it short and keep it to the point. And every time a character speaks, that dialogue has to do two things. It has to reveal something about who that character is, and it has to move the plot forward. Even if a character says, ‘I don’t know,’ it should still be part of the story’s engine.”

“So, the old ‘show, don’t tell’ is really important in a graphic novel.”

“Absolutely. What you show and how you show it matters. Every panel is a composition, and the way it’s read, top to bottom, left to right, is storytelling.”

“When you’re writing it, you’re writing the panel descriptions as well as the dialogue, correct?”

“Every panel.”

“How do you determine, on a page, how many frames or panels you’re using? Does the writer decide that?”

“Here’s another really good reason to go to the bookstore and find a book that feels like it has the same kind of weight or tone as your own vision. Look at it. Does it have three tiers or four? How many panels per tier? How many words per page? Do the counting, and then model your writing after that. Even if your story isn’t the same genre, say, you’re writing something that’s going to be banned instead of a silly macho space fantasy that won’t be, it’s a good exercise.”

“The first and second stories of your New York Trilogy, they’re completely different. The first has smaller panels throughout, and the next has a large panel with a lot of writing underneath.”

“The very first lesson in my Graphic Novel Lab would be that form follows function. You have to understand what your story is about, and then figure out what the form should be. In the first book of The New York Trilogy, the layout is a nine-panel grid. Over the course of the story, the main character, who pretends to be a detective, becomes obsessed, loses his apartment, his past life, and eventually his mind. What that story is really about is the nature of fiction itself. If this coffee cup isn’t called a coffee cup, is it still a coffee cup? At the start, the layout is rigid, every page in that nine-panel grid. By the end, as the character unravels, the gutters between panels widen, the panels stop being drawn with a ruler, and they start to wiggle. As he loses his grip on reality, the comic itself becomes unglued until the panels fall off the page. That’s why it’s designed that way. In the second book, the layout looks more like an illustrated text, an image on top, words beneath. It’s still a detective story, but this one is really about reading fiction. The detective has never read anything in his life. When he tries to read Walden, he can’t. He only knows how to read for facts. So when we reach that moment in the book, the layout itself changes. The pages turn into comics panels, forcing the reader to experience a different kind of reading. Then we switch back again. The format shifts to underscore the subtext: you can read passively, or we can make you read actively.”

“There’s not a lot of space. You’ve got action, a little dialogue, and you have to keep internal monologue to a limit, don’t you?”

“Not necessarily. Thought balloons and narrative blocks can serve as exposition when needed, but everything should support the story. You need to know your story, your plot, and your subtext before designing your comic. It may sound intimidating, but once you learn to think like a cartoonist, it becomes natural. That’s what I teach: a way of thinking.”

“Let’s talk about setting.”

“The setting and environment are essential. In the first book of The New York Trilogy, New York City is as much a character as the protagonist. In the second book, less so. By the third, the story hardly mentions New York at all, yet you still know where you are. So, yes, establish the world early. Don’t make the reader guess whether they’re in a space capsule or a time capsule. Do them a favor.”

“As a writer who writes for directors, I’m always careful not to cross that creative line. For the writer sitting at the desk putting this together, what’s the line they shouldn’t cross when working with a graphic artist?”

“Every collaboration is different. Think again of Bergman and Nykvist. At first, there was probably a lot of back-and-forth. But once a relationship is built, each trusts the other’s instincts. For the books I’ve worked on, I’ve done the sketches and scripts myself because I can draw. Both artists I’ve worked with collaborated closely to bring those sketches to life and then did the finished art. The best relationships are built on mutual respect. You find an artist whose style fits your vision, and you trust each other.”

“You’ve mentioned that your projects often find you, rather than the other way around. As a parting thought, can you talk about that passion? What turns a project from work-for-hire into something driven by obsession?”

“I have a peculiar career because I don’t do just one thing. I adapted Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy, co-wrote How to Read Nancy with Mark Newgarden, and wrote a memoir with my sister about growing up with our brother, who had autism, The Ride Together. None of these were projects I consciously chose. They demanded to be made. When I try to invent something just to invent it, I can tell when it’s hollow. The real ones insist on being created. It’s instinctual. I don’t have a choice. It’s compulsion, obsession. That’s how I’m built. Don’t start a graphic novel thinking you’ll sell it immediately, and don’t do it just because you liked Spider-Man as a kid. Do it because you can’t possibly do anything else. It’s what you were meant to do.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of the Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference, Killer Nashville Magazine, and the Killer Nashville University streaming service. Subscribe to his newsletter at https://claystafford.com/.

Two-time Eisner Award winner Paul Karasik began his career as the Associate Editor of Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly’s RAW magazine. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The New Yorker.

https://www.paulkarasikcomics.com/

Author photo credit: Ray Ewing

Clay Stafford talks with James Comey on “What Makes Stories Linger”

Clay Stafford interviews James Comey on writing stories that linger. Comey discusses character, truth in fiction, and why vivid scenes and authentic voices make stories unforgettable.

James Comey interviewed by Clay Stafford

James Comey is a figure the world thinks it knows. Former FBI Director, lawyer, public servant. His name has been bound to history’s headlines. Yet away from the noise of politics, which is a world of fiction itself, Comey has quietly stepped into another role: novelist. His fiction, drawn from a lifetime inside courtrooms, investigations, and the corridors of power, isn’t about retelling the past but about exploring human dramas at its center. In his books, readers encounter prosecutors and investigators who feel like old friends with scenes that linger long after the page is turned. In this conversation, I speak with Comey not about politics, but about the art of writing. What makes stories endure? What gives characters their staying power? Why truth, even in fiction, may be the most compelling force of all. “James, let’s talk about writing stories that linger. My wife always asks me when I’m reading a book, ‘How’s this one?’ And I’ll say, ‘This one, when I lie down to go to sleep, I’m still thinking about the people in it, why they’re doing what they’re doing. I can get in their heads. It sticks with me.’ That’s why I wanted to ask you about writing stories that linger. When you’re writing, do you ever think about how a story might stay with readers after they finish? Or do you focus on the moment, and if it lingers, it lingers?”

“I think it’s the latter. I’m not intentionally trying to make a story linger. But in a way, I am. I’m drawing from my own experiences. The coolest things I've been a part of. The hardest. Back then, I’d wake up thinking about a witness, a case, a judge. They were challenging, fascinating, rewarding. I try to bring readers into that world, show them those characters. Most are composites, but they’re based on real people I found interesting. If I can tell a story that feels as vivid as what I experienced, then it’ll stick with readers the way it stuck with me. I don’t set out with that as a conscious goal, but now that you’ve asked, maybe it’s always been close to the surface.”

“As a reader, what’s the difference between a story you forget the moment you put the book down, and one that haunts you for days, weeks, even years?”

“First, it’s good writing that lets me enter the story. Bad writing, sentences that are too long, language that’s overly complex, or fancy words block my way. It’s like being in a theater behind a tall person who blocks the view. I don’t want my writing to be like that tall person. I want a clear view of the stage. Then, I like the action on that stage to make you forget you’re in a theater. You feel like you’re there, like a non-playing character onstage, caught up in the conflict. The way to do that is to make the characters real, memorable, the kind of people you’d want to sit next to and just listen. If I can give you a clear view, make you forget the theater, and make the conflict compelling, that’s the recipe for a story that sticks.”

“Just curious—not for this—how tall are you?”

“I’m 6'8".”

“Holy cow. I’m 6'3", and I’m still looking up to James Comey.”

“Normal-sized person.”

“Unless I’m blocking everyone else in the theater. I bet you were intimidating in a courtroom.”

“Yes. Except with my wife. Early in my career, I was practicing a jury address in our small living room. Patrice watched me pacing back and forth and said, ‘That’s great, but why are you moving around like that?’ I said, ‘That’s what lawyers do.’ She said, ‘You look like a giraffe in heat. You’re tall enough to frighten people. Don’t move, and step back from the jury.’ From then on, in every trial, I stood still. Because she was right, movement would distract. People might start thinking about my size, my clothes, my feet, instead of listening. I didn’t want those distractions.”

“When you’re crafting a scene or character, is there a technique you use to make them stick in the reader’s mind?”

“I try to lavishly picture the scene before writing. How would it play out in real life? I build a mental map, then write. Afterward, I reread and ask: Does this feel real? Can readers see it? If yes, it may stick. I want people drawn into the conversation. If my characters speak with unnecessary flourishes, use words readers can’t grasp, or talk in perfect, complete sentences, it pulls you out. I’ve now written three novels, and I think I’m better at slowing down before writing, taking walks, imagining: Benny’s talking to Nora, where are they? What does it feel like? That patience makes it real.”

“Is there a specific character or scene readers told you they couldn’t shake?”

“Yes. In all three books, people have mentioned scenes that have stayed with them because they sparked strong emotions or were simply unique. That’s what I want: for the scene to feel like it happened yesterday, real in your mind because of how I wrote it.”

“Did that feedback ever surprise you? Or did you smugly say, ‘Yep, that’s exactly what I intended’?”

“No smugness. That kind of feedback usually comes first from my five kids: ‘Dad, you screwed this up,’ or ‘This scene is chef’s kiss.’ They’ll send emojis. When readers later say something similar, I’ve usually already heard it from the kids. What makes me happiest is when readers say starting FDR Drive feels like being back with old friends, Benny and Nora returning. That’s exactly what I want.”

“Speaking of old friends, when you’re creating unforgettable characters, do you have any habits that help make them feel real?”

“For me, it’s easier. One key character, Benny Dugan, is based on my dear friend Ken McCabe, the greatest investigator I ever knew, who died in 2006. I try to honor him through Benny. Ken wore no socks, carried a revolver on his ankle, spoke with a Brooklyn accent, and was enormous. He called me Mr. Smooth; I called him Mr. Rough. He’d offer to ‘throw someone a beating,’ and I’d say, ‘No, Ken, please don’t.’ He once drove me to LaGuardia, siren blaring, shouting at people. By the time we arrived, I was sweating, but he just said, ‘Say hello home,’ as if nothing had happened. Painful as it is that he’s gone, writing about him gives me an advantage. I also base Nora Carlton partly on my daughter, a prosecutor in Manhattan, and blend in traits from my other kids. Early on, I struggled writing a protagonist until I realized it had to be a woman. That unlocked everything. Writing became a labor of love, being true to the composites of the people I care about. Characters come alive because they’re grounded in real people I know and love.”

“We talked about ambiguity, threads left open versus tied up. Is there a sweet spot?”

“I don’t know. I rely on Patrice. She’s ‘every reader.’ She’ll tell me, ‘End this thread,’ or ‘Leave this one open.’ Almost always, she’s right. I’m married to a test reader, and that’s how I figure it out.”

“Your novels explore the justice system in depth. How do you keep the narrative gripping without drowning readers in detail?”

“By worrying about it constantly. I know the system inside and out, but readers don’t want to hear all that. I always ask myself: Am I giving too much? For example, in my current espionage book, I went deep into paint analysis. Patrice read it and said, ‘Drown some of these puppies. Way too much paint.’ Tom Clancy was brilliant, but often went too far into submarines and torpedo tubes. I don’t want to overwhelm like that. My guardrails are constant self-check and Patrice’s honest feedback.”

“Have you always wanted to be a writer?”

“No. I loved writing. I thought I might be a journalist. I never imagined novels. I always wrote, though: speeches, emails to the FBI workforce. Writing was part of me. My agent once pitched me to co-write a novel with James Patterson. I said no, I wanted to write myself. My nonfiction editor later encouraged me to try fiction, saying it gives me the freedom to show readers the worlds I know. I resisted, but once I started, I was hooked. It’s harder than nonfiction. You’re not just checking facts; you’re building a world. But I like complicated things. And I don’t need to invent car chases or helicopter jumps to make it exciting. Reality is exciting if told truthfully.”

“And maybe that truth is what makes a story linger.”

“I hope so. That’s my goal, to draw people in and have the story stay with them. And no, I won’t be writing sex scenes. My kids made me promise. But believe it or not, there’s not much sex in counterterrorism or espionage.”

“But there is dancing.”

“Yes, there is.”

“And that’s just vertical.” As the conversation wound down, what lingered was not just the stature of James Comey, the public figure, but the voice of a writer intent on making his characters real, his stories truthful, and his readers compelled to stay a little longer in the world he’d created. For Comey, fiction is not an escape from his past, but a means of reshaping it, transforming experience into narrative and memory into meaning. Perhaps that is the mark of every story that endures: it refuses to be forgotten, echoing long after the book is closed.

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of the Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference, Killer Nashville Magazine, and the Killer Nashville University streaming service. Subscribe to his newsletter at https://claystafford.com/.

James Comey has been a prosecutor, defense lawyer, general counsel, teacher, writer, and leader. He most recently served in government as Director of the FBI. He has written two bestselling nonfiction books, A Higher Loyalty and Saving Justice, as well as three novels in his Nora Carleton crime fiction series.

Clay Stafford talks with David Handler on “Character, Conscience, and Crime”

In this wide-ranging and thoughtful interview, Edgar Award-winning author David Handler joins Clay Stafford to discuss the craft of crime fiction, the role of character and conscience, and how to address social issues in fiction without sounding preachy. Full of wit, wisdom, and heart, Handler reminds us that the best crime stories are human stories.

David Handler interviewed by Clay Stafford

For Killer Nashville Magazine, I had the pleasure of chatting with David Handler—storyteller, observer, craftsman—to talk about the rhythm of crime fiction, the quiet power of character, and how to say something meaningful without ever preaching. What follows is honest, generous, and full of the kind of wisdom that only comes from doing the work. “David, let’s talk about thematic elements, which are so vital to your work. I grew up in a small town, so your latest book, The Man Who Swore He’d Never Go Home, really resonated with me. It felt different. Your novels often explore issues such as race, privilege, class, and pollution, weaving them seamlessly into the narrative. They never feel like lectures. How do you recommend other writers include meaningful issues in their work without sounding preachy?”

“For me, it starts with writing a lot of drafts. I usually let myself go ahead and write the lecture—get it all out. Then I step back and ask, ‘What do I really need here? What’s boring or extraneous? What moves the story?’ If something slows the momentum, I cut it.”

“So, the line is really about whether it’s boring?”

“That’s one test. But ‘extraneous’ is just as important. I always think like a reader. If my interest dips, something’s wrong. I’m the type who can read one page in a bookstore and know whether I’ll like the book. A lot depends on voice. If it reads like a Netflix screenplay in disguise, I’m out. I’m a fussy reader, which makes me a fussy writer. Pacing is crucial. Especially in crime fiction, you can’t give readers too much time to think, or the illusion might crumble. You have to keep them moving.”

“Like Hitchcock’s famous ‘icebox questions’.”

“Exactly. Hitchcock described those as questions people ask later, like when they’re getting a glass of milk from the fridge at midnight: ‘Wait, why was there a machine gun on that crop duster?’ It didn’t matter in the moment because he kept the story moving. You don’t want to push it too far, but forward momentum matters.”

“Lately, I’ve noticed more books focusing heavily on social issues, sometimes at the expense of story. It could just be what I’m reading, but it feels more common.”

“There was definitely a movement in the crime community a few years ago that leaned that way.”

“What you do differently, though, is include social issues without directing them. Your characters live within the issues. You’re not editorializing; you’re reporting, like a good journalist.”

“That journalism background helps. Whether I was writing criticism, doing profiles, screenplays, or columns, it’s all added up. But honestly, I rely a lot on instinct. After years of hard work, you develop a gut feeling for what belongs on the page.”

“And your tone helps. Some writers come to the page with anger. You bring a sardonic wit.”

“I do, but I don’t consider my books ‘comic mysteries,’ even though some critics label them that way.”

“I wouldn’t call them that either.”

“They have humor—Hoagy’s voice includes sharp observations, and the dialogue can be funny—but I think of them as serious novels. Early in the series, I pushed the humor harder. I was younger, trying to prove I could be funny. But then I took a twenty-year hiatus between the first eight books and the next set. Coming back, I was older, more relaxed. Now I let the voice come naturally. If it feels forced, I cut it. It’s like the difference between a twenty-two-year-old NBA player and a thirty-year-old one. The younger guy’s trying to impress, jump higher, run faster. The older player sees the game better, sets up the team, and plays the long game.”

“There’s a fairness to how you write. One character might view their world as totally normal, while another sees it as broken. You show both perspectives without judgment. That feels like your journalism again.”

“It probably is. I try to keep an open mind. I learn from my characters. One of the central themes in my work, and maybe my outlook on life, is that no one is who they seem to be. We think we know people, but we don’t. You might have friends who seem happy, then suddenly divorce. No one knows the truth of a relationship except the two people in it. I try to dig beneath the image someone presents and find out who they really are. People have layers. Vanity. Flaws. Strengths. And they’re more complicated than we realize. The older I get, the more I see how surprising they can be. I’ve had experiences in show business that would make your jaw drop, people you thought were friends turning on you. But I’ve also seen incredible kindness. For me, it always comes back to the people. The murder is an outgrowth of character and relationship.”

“That’s a powerful point. Social issues do reflect our environment. What advice do you have for writers who want to include them without being heavy-handed?”

“You can always tell when it’s heavy-handed or when a writer did a lot of research and refuses to cut any of it.”

“They throw it all in.”

“Subtlety matters. A little goes a long way. The issue should be organic to the story. Otherwise, it’s a distraction.”

“That’s what I felt reading your work. Pollution, dying towns, underfunded systems. They’re not soapboxes. They’re realities the characters live inside. You’re not explaining the cause of the decay; you’re showing what it’s like to live with it.”

“That’s the goal. Take the brass mill in the new book. One of the characters rarely talks about his father’s past, but the mill was a toxic place. Brass contains lead. The workers got sick. The groundwater was poisoned. It was non-union. Then it all collapsed when cheaper imports arrived from countries without environmental regulations. I’m not giving a ten-page lecture on it, but I want readers to feel it.”

“And we do—because your characters live it. Any advice for new writers?”

“Years ago, when I was doing celebrity profiles, I interviewed one of my childhood idols, Ray Bradbury. I was about twenty-six. I told him I wanted to be a novelist but didn’t know what kind of books to write. I had too many ideas and no direction. He said, ‘Sure you do.’ I asked, ‘I do?’ And he said, ‘Yeah. Write what you love to read.’ I got into the hotel elevator afterward, and I felt like I’d just spoken with the Dalai Lama. ‘Write what you love to read.’ It’s simple, but it changed me. Don’t think about the marketplace. Don’t chase trends. Just write the stories that move you.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference, The Balanced Writer, and Killer Nashville Magazine. Subscribe to his newsletter at https://claystafford.com/.

David Handler is the Edgar Award-winning author of several bestselling mystery series. He began his career as a New York City reporter. In 1988, he published The Man Who Died Laughing, the first of his long-running series starring ghostwriter Stuart Hoag and his faithful basset hound Lulu.

Clay Stafford talks with Eric LaRocca on “Writing Transgressive Literature Without Apology”

In this candid conversation, horror author Eric LaRocca explores the power and purpose of transgressive literature, discussing how pushing boundaries creates emotional truth and empathy in unsettling storytelling. From influences like Clive Barker to navigating backlash, LaRocca shares his uncompromising vision and why provoking readers is central to his craft.

Eric LaRocca interviewed by Clay Stafford

In this bold, unfiltered conversation, horror author Eric LaRocca tells me about the purpose of transgressive fiction, the emotional truths behind unsettling storytelling, and the liberating power of pushing past boundaries. With a career built on polarizing reactions and visceral storytelling, LaRocca shares how discomfort, provocation, and empathy coexist in his work—and why that tension is exactly where his voice belongs. “Eric, I found your book quite immersive.”

“Thank you. That means a lot. I appreciate it.”

“I don't know that it was comforting—it didn’t exactly leave me feeling safe—but it was certainly immersive. Which, I think, was exactly your intention.”

“Yeah, definitely. I'm not interested in comforting readers.”

“And that's where I want to start—writing that challenges rather than soothes. I want to talk about the pleasures and perils of bold, transgressive literature. Most people don’t push boundaries like you do, and I think it’s worth exploring what happens when writers dare to go there.”

“I think so too. One of my favorite transgressive writers, Samuel R. Delany—who’s usually known for science fiction—once said something that really stuck with me. He wrote a book called Hogg, one of the most transgressive things I’ve ever read. In an interview, he said the point of transgressive literature is to move forward the barometer of what’s acceptable—what’s palatable—and I agree. Each time something outrageous is published, it shifts the line. It tests comfort levels. What was once brutal or grotesque becomes more accepted. That’s what I try to do with my work—move the line.”

“What drew you personally to this side of storytelling? What’s the creative reward in pushing those boundaries?”

“I've always been drawn to the dark, the macabre, the unsettling. Even as a kid, my parents noticed I leaned toward the grotesque. I grew up in a small, isolated Connecticut town and spent a lot of time at the library—reading Roald Dahl’s children’s stories first, then his adult work. Hitchcock. Agatha Christie. Poe. Hawthorne. Gothic fiction became a big influence. There’s catharsis in it—especially Gothic literature. It’s emotional, taboo, unconventional. And transgressive fiction builds on that—it’s a burst of energy, a pageantry of the grotesque.”

“You mentioned transgressive fiction as catharsis. Was there a writer who opened that door for you?”

“Clive Barker. In high school, his work showed me what fiction could really do. He was a gateway. From there, I discovered Poppy Z. Brite, Kathe Koja, Dennis Cooper—who’s one of my favorites. His book Frisk is unsettling in a way that stays with you. Bret Easton Ellis, too. That’s how I fell into this netherworld of depravity.”

“Which brings us to something you said earlier—people can be uncomfortable seeing characters doing horrible things. There’s often pushback.”

“Right. There’s this idea that character representation needs to be clean, sanitized. And I get that there’s a spectrum, but I’m interested in the grotesque end. That’s where I live creatively. For a long time, we didn’t see unsanitized horror. It’s coming back, though, and I think it’s wonderful. There’s space now for graphic, messy, problematic characters—and I want to keep exploring that.”

“When you’re writing something deeply unsettling, how do you know whether it’s necessary or if it’s just shock value?”

“Sometimes it is shock value. I think of Harlan Ellison—his story I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream is one of my favorites. He got criticized for being shocking, and he said, ‘Yes, that’s the point.’ It’s supposed to disturb you. I feel the same. I want to provoke people—not harm them—but shake them up. That’s what books can do.”

“Unless someone gets hit in the head with one.”

“Right. But seriously, books have power. Especially transgressive ones. They change perspective. Broaden minds. I don’t want people finishing my book and thinking, ‘That was fine. Three stars.’ I want one star—'This is vile, I hated it’—or five stars—'This is vile, I loved it.’ No middle ground. I want intense reactions.”

“But how do you stay true to that artistic vision when you know it might alienate readers—or publishers?”

“I used to care. A lot. I wanted people to like me. But I’ve grown out of that. Most readers will never truly know me. I’m just a name on a book cover to them. And as for publishers—sure, there’s sometimes compromise. When I worked with Blackstone, there were things in the manuscript they wanted removed—too graphic. I wasn’t thrilled, but I understood. Publishing is a team effort. You have to protect your vision, but sometimes, a little compromise helps the book reach more people.”

“Did cutting those scenes hurt?”

“Yeah. It wasn’t easy. But I made peace with it. I could’ve refused, but then maybe the book doesn’t get out there the same way. You pick your battles.”

“Ever had a moment where you asked yourself, ‘Am I going too far?’”

“Not really. I might check in with my friends—'Will this upset people?’—but ultimately, I want to provoke. That’s my nature.”

“And when you refuse to play it safe, what’s the emotional reward for you?”

“Hearing from readers—especially young readers—who say, ‘Thank you for showing this.’ That’s the reward. Seeing themselves reflected, unsanitized, gives them permission to write their truth. That’s what Clive Barker and Dennis Cooper did for me. To be that for someone else is everything.”

“But the downside is that distribution becomes a hurdle. Big publishers don’t always embrace transgressive work.”

“Exactly. It’s niche, and publishers can be risk-averse. I was lucky—Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke went viral. Tiny indie press, but the book blew up. You can’t predict what hits. But transgressive fiction can struggle to find a wide audience.”

“Have you faced blowback?”

“Definitely. Especially online. People get upset. But that’s part of the job. You can’t write this kind of work and expect universal praise.”

“Have those moments ever made you second-guess your creative direction?”

“In quiet moments, sure. I’ll ask, ‘Did I cross a line?’ But it always comes back to: Do I want to write bold, honest work? Or do I want to write what sells? And there’s no wrong answer. Sometimes you need to pay the bills. I’m experimenting more now. I’ve got a book coming out with Saga Press—it’s still horror, still me, but more restrained. It’s okay to explore your range.”

“For writers who want to take risks, but are scared of backlash—what would you say?”

“Have a strong support system. Loved ones you can lean on. That’s everything. If transgressive writing is in your heart, it can be life-changing—but it’s not for everyone. You need grounding.”

“And when you’re writing these brutal characters, do you still feel compassion for them?”

“Absolutely. That’s something I’ve heard from readers—that there’s empathy in my work. Even when it’s violent and ugly. I try to understand my characters, even when they’re doing terrible things. That empathy needs to be there—or else it’s just gore. At Dark, I Become Loathsome is a brutal book, but I cared deeply for Ashley. He’s obsessed with horrible things, but I felt for him. That feeling matters.”

“I felt it too. Even amid the darkness, there was this little candle of hope. You never snuffed it out entirely.”

“Thank you. That means a lot.”

“What do you hope readers carry with them when they close the book?”

“A deeper understanding of humanity. Of themselves. The people I write about—they exist. And we’re losing compassion. We’re losing grace. I want readers to reflect. Think about grief, trauma, sexuality. I don’t write with a moral message in mind—but maybe, as Delany said, the line moves a little. Maybe compassion enters the chat. That’s the hope.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference, The Balanced Writer, and Killer Nashville Magazine. Subscribe to his newsletter at https://claystafford.com/.

Eric LaRocca (he/they) is a 3x Bram Stoker Award finalist and Splatterpunk Award winner. He was named by Esquire as one of the “Writers Shaping Horror’s Next Golden Age” and praised by Locus as “one of strongest and most unique voices in contemporary horror fiction.” He currently resides in Boston, Massachusetts, with his partner.

Clay Stafford talks with Joyce Carol Oates “On Being Her Own Person”

In this conversation, Joyce Carol Oates reflects on her new collection Flint Kill Creek, the evolving political relevance of her historical novel Butcher, and her enduring drive to experiment across genres. With insight into her writing process, teaching philosophy, and thoughts on literary career-building, Oates offers rare wisdom for writers navigating both inspiration and discipline.

Joyce Carol Oates interviewed by Clay Stafford

I first met Joyce Carol Oates when she was the John Seigenthaler Legends Award winner at the Killer Nashville International Writer’s Conference. She is a prolific writer, a modern-day legend, and a professor at NYU and Princeton, where her fortunate students learn from one of the best living writers today. When her new collection of short stories came out, Flint Kill Creek, I reached out to her to see if we could chat about the new book, writing in general, and how to prepare oneself for a career as a writer. My goal, because she is both a prolific writer and a teacher, was to see if there was some Holy Grail that writers could discover to create a successful career. Fortunately, we may have stumbled upon it. “Joyce, someone such as you who's written over a hundred books, how do you consistently generate these fresh ideas and maintain this creative energy you've got going?”

“Well, it would not interest me to write the same book again, so I wouldn't be interested in that at all.”

“I wonder if some of it also has to do with all the reading you do. It's generating new ideas coming in all the time.”

“I suppose so. That's just the way our minds are different. I guess there are some writers who tend to write the same book. Some people have fixations about things. I don't know how to assess my own self, but I'm mostly interested in how to present the story in terms of structure. Like Flint Kill Creek, the story is really based very much on the physical reality of a creek: how, in a time of heavy rainfall, it rises and becomes this rushing stream. Other times, it's sort of peaceful and beautiful, and you walk along it, yet it's possible to underestimate the power of some natural phenomenon like a creek. It's an analog with human passion. You think that things are placid and in control, but something triggers it, and suddenly there is this violent upheaval of emotion. The story is really about a young man who is so frightened of falling in love or losing control, he has to have a kind of adversarial relationship with young women. He's really afraid to fall in love because it's like losing control. So, through a series of incidents, something happens so that he doesn't have to fall in love, that the person he might love disappears from the story. But to me, the story had to be written by that creek. I like to walk myself along the towpath here in the Princeton area, the Delaware and Raritan Canal. When I was a little girl, I played a lot in Tonawanda Creek, I mean literally played along with my friends. We would go down into the creek area and wade in the water, and then it was a little faster out in the middle, so it was kind of playful, but actually a little dangerous. Then, after rainfall, the creek would get very high and sometimes really high. So it's rushing along, and it's almost unrecognizable. I like to write about the real world, and describe it, and then put people into that world.”

“You've been writing for some time. How do you keep your writing so relevant and engaging to people at all times?”

“I don't know how I would answer that. I guess I'm just living in my own time. My most recent novel is called Butcher, and I wrote it a couple of years ago, and yet now it's so timely because women's reproductive rights have been really under attack and have been pushed back in many states, and it seems that women don't have the rights that we had only a decade ago, and things are kind of going backwards. So, my novel Butcher is set in the 19th century, and a lot of the ideas about women and women's bodies almost seem to be making like a nightmare comeback today. I was just in Milan. I was interviewed a lot about Butcher, and earlier in the year I was in Paris, and I was interviewed about Butcher, because the translations are coming out, and the interviewers were making that connection. They said, ‘Well, your novel is very timely. Was this deliberate?’ And I'm not sure if it was exactly deliberate, because I couldn't foretell the future, but it has this kind of painful timeliness now.”

“How do you balance your writing with all this marketing? Public appearances? Zoom meetings with me? How do you get all of it done? How does Joyce Carol Oates get all of it done?”

“Oh, I have a lot of quiet time. It's nice to talk to you, but as I said, I was reading like at 7 o'clock in the morning, I was completely immersed in a novel, then I was working on my own things, and then talking with you from three to four, that's a pleasure. It's like a little interlude. I don't travel that much. I just mentioned Milan and Paris because I was there. But most of the time I'm really home. I don't any longer have a husband. My husband passed away, so the house is very quiet. I have two kitties, and my life is kind of easy. Really, it's a lonely life, but in some ways it's easy.”

“Do you ever think at all—at the level you're at—about any kind of expanded readership or anything? Or do you just write and throw it out there?”

“I wouldn't really be thinking about that. That's a little late in my career. I mean, I try to write a bestseller.”

“And you have.”

“My next novel, which is coming out in June, is a whodunnit.”

“What's the title?”

“Fox, a person is named Fox. That's the first novel I've ever written that has that kind of plot. A body's found, there’s an investigation, we have back flash and backstory, people are interviewed. You follow about six or seven people, and one of them is actually the murderer, and you find out at the end who the murderer is. The last chapter reveals it. It's sort of like a classic structure of a whodunnit, and I've never done that before. I didn't do it for any particular reason. I think it was because I hadn't done it before, so I could experiment, and it was so much fun.”

“That's one of the things readers love about your work, is you experiment a lot.”

“That was a lot of fun, because I do read mysteries, and yet I never wrote an actual mystery before.”

“Authors sometimes get the advice—which you're totally the exception to—of pick one thing, stay with it, don’t veer from that because you can't build a brand if you don't stick with that one thing. Yet you write plays, nonfiction, poetry, short stories, novels, and you write in all sorts of genres. What advice or response do you give to that? Because I get that ‘stick with one thing’ all the time from media experts at Killer Nashville. You're the exception. You don't do that.”

“No, but I'm just my own person. I think if you want to have a serious career, like as a mystery detective writer, you probably should establish one character and develop that character. One detective, let's say, set in a certain region of America so that there's a good deal of local color. I think that's a good pattern to choose one person as a detective, investigator, or coroner and sort of stay with that person. I think most people, as it turns out, just don't have that much energy. They're not going to write in fifteen different modes. They're going to write in one. So that's sort of tried and true. I mean, you know Ellery Queen and Earl Stanley Gardner and Michael Connolly. Michael Connolly, with Hieronymus Bosch novels, is very successful, and they're excellent novels. He's a very good writer. He's made a wonderful career out of staying pretty close to home.”

“Is there any parting advice you would give to writers who are reading here?”

“I think the most practical advice, maybe, is to take a writing course with somebody whom you respect. That way you get some instant feedback on your writing, and I see it all the time. The students are so grateful for ideas. I have a young woman at Rutgers, she got criticism from the class, and she came back with a revision that was stunning to me. I just read it yesterday. Her revision is so good, I think my jaw dropped. She got ideas from five or six different people, including me. I gave her a lot of ideas. She just completely revised something and added pages and pages, and I was really amazed. I mean, what can I say? That wouldn't have happened without that workshop. She knows that. You have to be able to revise. You have to be able to sit there and listen to what people are saying, and take some notes, and then go home and actually work. She is a journalism major as well as something else. So I think she's got a real career sense. She’s gonna work. Other people may be waiting for inspiration or something special, but she's got the work ethic. And that's important.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference and the online streaming creative learning platform The Balanced Writer. Subscribe to his weekly writing tips at https://claystafford.com/

Joyce Carol Oates has published nearly 100 books, including 58 novels, many plays, novellas, volumes of short stories, poetry, and non-fiction. Her novels Black Water, What I Lived For, and Blonde were finalists for the Pulitzer Prize; she won the National Book Award for her novel them. https://celestialtimepiece.com/

Clay Stafford talks with Callan Wink “On Succeeding as a Part-Time Writer”

Callan Wink talks about the winding journey to publishing Beartooth, the balance of writing part-time while guiding anglers in Montana, and why it's okay to put a manuscript in the drawer—just not forever.

Callan Wink interviewed by Clay Stafford

In spring, summer, and fall, Callan Wink can be found guiding flyfish anglers in Montana. In the winter, he surfs in Costa Rica. Callan’s new book, Beartooth, is out, and I wanted to talk to him about his success as a part-time writer. I caught up with Callan in Costa Rica (he’s already made the migration) after a morning of surfing and before a walk on the beach. “Callan, let’s talk about the writing and editing process, specifically about Beartooth. I heard it’s had a circuitous route. Can you tell us about your process and the trajectory of this particular book?”

“I've probably had the premise in my head for a long time, over ten years, and I wrote it as a short story when I was writing more short stories. It was an okay short story, but it was thin. I felt like there was more, so I never tried publishing it. Then I wrote this long, 400-page, boring novel. It had a great first fifty-sixty pages, I thought. It was one of my first attempts at writing a novel. It didn't go well, so I put it away for a long time and wrote my other two books in the meantime—another novel and that collection of short stories. Then, I came back to it a couple of years ago. I wanted to write a collection of novellas. I still thought the first fifty-sixty pages were really good, so I just went back to this one and brutally cut out everything boring, which was a lot of it.”

“Which is a good move.”

“It was pretty good. It was eighty-ninety pages, and I had a couple of other novellas. My agent and I tried to sell that as a collection of three novellas, and we had interest, but the publishers, in the end, said a collection of novellas is a hard sell, but they were all like, ‘We like this one, Beartooth. Can you make it longer?’ I'm like, shit. It was longer at one point. But anyway, then I went back. I also rewrote and developed other things. I do think it made it better. It's still a short novel, but I feel like the stage it's at now is the best of all those iterations. If I learned anything from this one, it was if you have a good premise, don't give up on it, which I'm prone to do. I like to keep moving on to other things, and if something doesn't work out quickly and easily, I'm like, it's not meant to be. But good premises are a little harder to come by, I'm realizing as I get older. If you have a good one, it behooves you to keep working on it.”

“I find your writing life fascinating. For those struggling with family and work, how do you balance writing with your other responsibilities as a part-time writer?”

“I have a lot of respect for people who are producing when they have families and full-time jobs and things like that. I’m a single person. My summer, spring, and fall job is very physically and emotionally taxing at times. It's long days, and I'm tired and don't write. But I do feel like when you have constraints on time, it does make you a little more likely to buckle down when you do have time. I don't work at it all year, but when I do, I try to be disciplined and get my 1,000 words in every day in the winter and at least feel like I'm generating some stuff. I don't know if it's the best way, quite honestly. I feel like working on it all year is probably better for writing novels. But I do feel like it's probably going to mean that I'm going to be producing shorter novels because it's a little easier to get one in the bag in a few months or a rough, rough draft, as opposed to some epic, sprawling thing where you’ve got to be in it for years every day.”

“What strategies do you use to stay motivated and maintain that momentum during writing on your schedule?”

“That's a good question. I don't love the process of writing that much, quite honestly. Sometimes it's fun. You feel like you're getting somewhere, and things are flowing. I still really enjoy that feeling, but those times are overshadowed by vast periods of What am I doing? None of this is going well. But it's just always what I've done. It's like a compulsion. It's not something I will probably stop doing anytime soon. I was doing it without thinking that this was what I would do for my job. It was always like, I'm a fishing guide and write stuff. I used to write poetry. It wasn't very good, but I did that at a young age, and I guess I've always been writing, so I feel weird not to be at least thinking about it. Even if I'm not writing every day, I usually think about it most days. So yeah, for whatever reason, it's this compulsion I have. I don't necessarily feel like I need to be motivated too much other than to start feeling guilty if I haven't been working on something. It’s ingrained at this point. I don't see it changing anytime soon. Setting a small goal in terms of productivity is a good thing. I've always tried to do one thousand words daily, and I don't hit it every day, but I can most days. Sometimes it takes me a couple of hours, and sometimes it's like most of the day. But if I can get that, I can go about the rest of my day. I can go to the bar, surfing, or whatever.”

“Do you outline? Or do you sit down and start writing?”

“I do feel like maybe the outline for novels is a good way to do it. When I've tried to do it in the past, it feels like when you're doing the outline, you're like, Okay, this is great. I'm setting up this framework, and this is all gonna go a lot easier. But then it always seems to lack some organic characteristics that when I write happens. I don't outline much, but honestly, it might be easier if I did. It hasn't worked for me at this point. I usually try to write and have a point I want to get to in the next maybe ten pages. And I get to that point. And then, I think about what I want to do in the next ten pages. So, there is not a lot of outlining going on.”

“When you were writing Beartooth, were there any unusual challenges or anything you found challenging in developing the characters? And how did you overcome those?”

“I guess the challenge is the relationship between the two brothers, which evolved over time in the rewriting. It was all challenging, to tell you the truth. Several early readers said we want this mother character to be more developed. From the beginning, I had a pretty good idea about the two brothers and how I wanted them to be and act in the story. I knew she would be this absent figure, but when she returned, trying to create her more as a fully fleshed-out character was one of the more challenging things in the book for me. I can write a thirty-something-year-old man pretty well. Writing a sixty-year-old woman is a little bit more of a stretch. It's something I had to lean into a little bit more.”

“What part of the novel writing process is the most enjoyable?”

“There are fun moments, and finishing that first draft is sort of fun. You feel like you've done something. This is only my second novel, but weirdly, it’s like every one gets more challenging because you know how much work you have ahead. My first one, I had no idea. I thought I was pretty much there when I finished that first draft. No, not even close. There's so much work. Knowing how much work is coming up and going into it can be a little oppressive. Now, I think a lot of my challenge is to not think about that and try to recapture the going forward with it that I did in my first novel, where I didn't have any expectations. Weirdly, trying to write more like I did when I was first starting is something I have to try to do more now.”

“Do you think education sometimes messes with your mind? You know, you love writing, and then you go to school, and sometimes there are rules and things that start coming in your head.”

“For sure. The writing education I've had was significant in that I had rooms full of readers who had to read my stuff and give me feedback, so getting feedback as a writer is, I think, super crucial and challenging to do, often when you're outside of a writing program, for a lot of writers, unless you have this group of readers that you feel like are invested in your work and things like that. That can be a rare thing. When you have that, you feel like you are getting the feedback you need. But when you're on your own, you're just kind of on your own. I've taught writing a couple of times, and I enjoyed it for the most part. But I noticed that when I was trying to write, sometimes things I said in class to my students would come into my head. It was weird. I didn't like it, quite honestly, because there were things I was telling my students, and I was trying to apply them to my writing, which was weirdly counterproductive.”

“Putting yourself in a box.”

“A little bit. I was judging what I was writing based on something I was trying to tell my students in class that day, which wasn't helpful. I'm always impressed by people who are good writing teachers and also produce a lot of stuff. I don't have that ability.”

“Sometimes two different hats.”

“A little bit. I’ve got a lot of respect for writing teachers who are also good writers and working a lot because it's taxing.”

“For a novel with no deadline, no due date, how do you know when you're in that phase where it's like, ‘Okay, the draft is great. I need to start editing to get it ready to submit.’ At what point do you know you're at that point? Other than ‘I'm sick of it, and I'm ready.’”

“Yeah, well, there's that.”

“No, don't! Don't go to that one.”

“Generally, if I'm at the point where I'm just dinking around with commas and stuff, I'm like, ‘All right, it's time to get some other eyes on it.’ Once I'm either at the very sentence-level stuff or where I can't seem to access it anymore in a way that makes any substantial changes, then I at least need to put it away for a long time or send it to somebody.”

“If you're sending it to somebody, how do you handle the feedback from your beta readers or critique partners?”

“At least for me, I'm lucky, and I don't have a large pool of people I send stuff to. My agent, luckily, is great at reading stuff. I don't just send him whatever first draft junk I wrote. I try to respect his time because he's a busy guy. But, if I've been working on something and I think there's some merit, he'll give me good notes–just like a letter, and usually, it's pretty insightful. And then I try to go back into it with that. I think one thing that I've realized in doing this now is that there's a lot of benefit for me in putting something away for a significant amount of time because then you go back to it with fresh eyes. There are things that you can't see when you're so immersed in it. Putting something away is big for me.”

“But that disheartening feeling, too, when you come back two years later and go, ‘This was so good. I can't wait to read it,’ and then you're like, ‘This is so bad. I can’t believe I wrote it.’”

“I'm like eroded. I have probably three fully different novel drafts that I will never publish. They may have been things I needed to write to get out of my system for other things to come in, but if I were to look at the number of pages I've written on a scale compared to the ones I've published, that would be sad. I don't like to think about that.”

“How do you determine which parts of your novel need the most significant revision? You were talking about how the mom needed to be expanded. What clues do you have about that without third-party influence?”

“One thing I've noticed in my stuff is sometimes I get caught up in how to get from point A to Point B. I know I want to get to Point B at some point, and then there are all these steps. I get hung up in there. It gets boring while I'm just trying to get the characters from here to there, and that's something that can be hard to see if you haven't put it away for a while. But for whatever reason, coming back after a significant amount of time away from it, I'm more able to see the gaps or areas where you can cut and get to the more interesting stuff. Knowing when to end a scene and move on to something interesting is something that comes in editing. I've become more aware of it now; it is just moving along.”

“So, how do you solve that? Is it pretty much good, boring, and good stuff, and then we just put some transition or something in there and remove the boring? How does that work?”

“I think what I've noticed in my first drafts is maybe I don't give the reader enough credit or something because I'm still trying to figure it out in my own head where I need it to be very clear and sort of step by step to from point A to point B. Going back in, I'm like, ‘Oh, a reader is going to infer. We don't need all of that. We can get right into the next thing.’ I realized it early in short story writing, which is very scene-dependent. The gaps in between add to the effect of the story. Knowing when to transition is a big part of writing a short story, at least how I've done it, which translates into a novel. I try not to look at the sort of blank spots as much as a negative thing. I mean, you still need to have continuity and for readers to be able to follow along, but having blank spots in various areas when you're advancing is not the end of the world, and often is better, quite honestly.”

“You referenced inference. That's sometimes good because it invites the reader to think and contemplate where you're going, what just happened, or what did happen.”

“Definitely. A reader's imagination can do much better writing than I can. So, allowing the reader to use their imagination is crucial.”

“What advice would you give aspiring novelists about building a sustainable career while working at it part-time?”

“That's a good one, you know.”

“You're doing what you want to do, right?”

“Totally. I love it.”

“Your summertime gig, and you do not want to give that up?”

“I'm very fortunate. I'm not making a ton of money, but my lifestyle is a ten on a scale of one to ten. I have a good program, and I guess everyone's different. I think some people like going the academic route. For me, just having another job that is not writing is crucial. Many writers I've admired have taught as their job, but many also had other careers. Many writers have had just some job that was completely different than writing. And for me, that's important, and I would recommend that. And maybe not even go to school to write, to tell you the truth. Read a lot, and then study biology or something. It's kind of what I probably should have done.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. Subscribe to his newsletter at https://claystafford.com/

Callan Wink has been awarded fellowships by the National Endowment for the Arts and Stanford University, where he was a Wallace Stegner Fellow. His stories and essays have been published in the New Yorker, Granta, Playboy, Men’s Journal, and The Best American Short Stories. He is the author of a novel, August, and a collection of short stories, Dog Run Moon. He lives in Livingston, Montana, where he is a fly-fishing guide on the Yellowstone River. https://www.spiegelandgrau.com/beartooth

Clay Stafford talks with Heather Graham on “The Business of Writing”

Heather Graham joins Clay Stafford for a candid conversation about the business side of writing—from handling finances and choosing representation to navigating social media and protecting rights. With wit and wisdom, Heather shares lessons learned across her prolific career and offers invaluable advice to emerging writers.

Heather Graham interviewed by Clay Stafford

Author Heather Graham is incredible in many ways: her prolific and stellar writing style and habits, her support and encouragement of other authors, and her inspiration and support of many beyond the writing field. I know of few authors who view writing and attention to their readers, as does Heather Graham. It was a pleasure catching up with Heather when she was in New York City during one of her busy tour schedules. Since she is so prolific, I thought I’d ask her about business, a subject that many writers view through a fog. “So, Heather, let’s jump right in and ask, what’s the biggest financial mistake you see new writers making early in their careers, and how can they avoid that?”

“I am horrible with finances, so I don't know if I'm the one to ask.”

I laugh aloud. “Okay, with that build-up, you crack me up. Can you speak from experience, then?”

“People come at writing from so many different venues. Some are keeping day jobs and writing on the side. They have their day job, so they don't have to worry about finances too much. And, of course, publishing is ever-changing. But always ensure you have your next project ready to go, and then don't be as bad with money as I am. I don't know what to say because you never know. Do you want to go traditional? Are you going to get a multi-book contract? Are they buying a one-off project? Are you collaborating with Amazon? It depends so much on what you're doing. One of the main things you must learn—that I'm still working on—is that when you're on contract, you'll get so much and then so much later on publication. And then the problem is, of course, it's never guaranteed income. You have to learn to watch the future more than anything else.”

“There are writers I speak with who have things they want to write, but frankly, we know that some of those are not commercial. How do you balance your creative freedom with what the market wants?”

“That's one thing I tell people to be careful about. If you are putting up on Amazon, you can be fast. You can catch the trend. But if you're writing for one of the traditional publishers or a small press, it's usually going to be a year before your work comes out. You want to be careful about writing to trends because that trend could be gone by the time something comes out. My thought is, if it's something you love, do it. Otherwise, be careful. You always have to write what you love. What makes you happy, too, because your excitement comes out on the page.”

“What are some of the common pitfalls that you might see that writers don't think about and should have been aware of, even with representation—things that could lead to mistakes?”

“First of all, you need to do your homework. Doing your research for beginning writers is one of the most important things you can do. Find out what agents enjoy what you're doing. Find out what houses are buying what you're doing. I think that's one of the best things. Somebody just spoke at World Fantasy who is an editor, but her husband is an agent. He has out there that he does not handle young adult, and he'll get a million young adult things anyway. The most important thing, I think, is to be savvy about what's going on. I didn't know any agents or editors when I started, but I can't recommend groups and conventions enough because you meet others. You're always going to hear more stories. You're going to hear what's happened. You're going to be introduced to editors and agents, and you're going to hear from friends, ‘Oh, my gosh, yes, that's exactly what they're looking for.’ Because I have covered my bases, I belong to HWA, MWA, International Thrillers, and RWA, and I have never met such a nice group of people. It's like nine-hundred-and-ninety-nine out of a thousand are great, and everybody shares. The good majority are supportive.”

“Because time is finite and money is finite, for a beginning author, where should authors focus their promotional and marketing strategies? And where should they not because they should be writing instead of doing that?”

“I'll tell you something I'm not very good at, but I have learned that TikTok and BookTok are some of the biggest ways you can do things now. Social media is free. When you're on a budget, using social media is great. I have been traditionally published for a long time, and they have publicity departments and marketing departments. More so today, even in the traditional houses, they want you to do a lot of your own promotions. I think for many of us, it is hard because the concentration is more on what I'm writing. It's a good thing to try to get out there and learn. And I am still working on this: learning how to be good on social media.”

“And technology changes.”

“Yes. Constantly.”

“New opportunities open up.”

“Yeah, that's just it. You have to be ready for change.”

“What are some red flags to look out for when you're getting an agent or signing a contract with a publisher?”

“Again, I've been lucky. I didn't start out with an agent and really had no idea what I was doing, but I sold a short horror story to Twilight Zone, and then Dell opened a category line, and I sold to Dell. But they were contemporary, and I had always wanted to write historical novels, and I had a couple in a drawer. I always remember when I sold because I stopped working with my third child and had my first contract with my fourth child. There’s just that year and a half, or whatever was in there, but when I had the historicals, and nobody wanted to see them, there was a woman in the romance community who had a magazine called Romantic Times, and she came to Florida with one of her early magazines. It had an ad that said Liza Dawson at Pinnacle Books was looking for historical novels, and I'm like, ‘Let me try. Let me try, please.’ They did buy the historical, but at the time, everybody was very proprietary about names, so Shannon Drake came into it. I was doing historicals under Shannon Drake, but the vampire series wound up coming under that name, too. It just depends on what you're doing. There are two lines of thought. One is that you need to brand yourself. You need to be mystery, paranormal mystery, sci-fi. You need to brand yourself as something. That’s one idea that can be very good, but I also loved reading everything. There are many, many different things that I have always wanted to write. I have been lucky; I have done it. Whether it was a smart thing or not, I don't know. I can very gratefully say that I have kept a career, and I have been able to do a lot of the things I've wanted to do.”

“When the boilerplate comes, it says they want all rights for everything. What rights should a writer retain?”

“When this whole thing happened where I was selling to a second company, that's when I got an agent. And again, we're looking at the same thing. Study what the agents are handling, what they're doing, and who they have. When we’ve done negotiations, I've usually been asked to leave because I am not a good negotiator. You need to listen to your agent and the agent's advice. Now the agent, a lot of the time is going to know, ‘No, no, no, we have to keep the film rights. They never do anything with them,’ or ‘No, let them have them because they just might use it.’ An agent is going to know these things better because they do it on a daily basis. And then the other thing is, your agent gets you paid. Instead of you having to use your editorial time talking to somebody saying like, ‘Could you please send that check?’ the agent will do that for you.”

“Let's go back a minute. You talked about social media. What kind of mistakes do you see writers making on social media? I can think of a few, but what are your thoughts?”

“I'll tell you what gets me, and this is purely as a reader, and I will be a reader till the day I die. I love books. I want people to read, too. As a reader, though, when I'm on social media, don't, don't, don't put out there, ‘Oh, you've got to read…’ or ‘This is the best book ever,’ because to me that means no. It's going to be my decision as a reader whether it's the best book ever. Just say, ‘I hope you'll enjoy this,’ or ‘This is about…’ or ‘I'm very excited about…’ or whatever. You don't want to say, ‘Gee! This may be pure crap, but buy it anyway.’ You can tell people what something is about, why you're excited about it, and you hope they'll enjoy it. But this is more my opinion as a reader than as a writer. Don't tell me, ‘It's the best thing ever. You're going to love it.’ Let me make that decision.”

“You talked about conferences and networking. What are some common mistakes that writers make when it comes to their professional development? Where are they lacking? What do you see value in?”

“Again, I think conferences and conventions are some of the most important things you can do. It helps if you want to volunteer and help get people going. That way, you meet more people, and you can interact more with those running the conferences, who have probably been around for a while and have some good advice. One of the worst things you can do is spend a lot of time whining or complaining about things that can't be helped. Things do happen sometimes. Books don't arrive, or the seller didn't come through. Don't make life miserable for other people. I'm not saying you shouldn't fix something if you can, but sometimes things can't be fixed, and then you have to let it go. And there are different types of conventions. You have Thriller Writers, Bouchercon, Killer Nashville. You have the Bram Stoker Awards, which are relatively big. We have something down in Florida called Sleuthfest. I love Sleuthfest, and it's very easy. It's good to get involved. It's an investment in your future. I know I was looking for money to pay the Chinese restaurant when I first started out, so sometimes you just don't have it when you're beginning your career. And that's why you try to do the things that are closest to you. Just become involved with a group that maybe meets at a library. Anything like that. There are online groups these days. The very best perk we get out of it is our communities.”

“What advice would you give people? Maybe, ‘I wish I had known this when I started out…’”

“I wish I had known what an amazing community the writing community was and to get involved, and therefore, I would have learned so many things I didn't know. I have two lines of advice. One, sit down and do it. Be dedicated to yourself. Be dedicated to your craft. And then, get involved. Find like-minded people because they will be wonderfully helpful and encouraging.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. https://claystafford.com/

Heather Graham is the NYT and USA Today bestselling author of over two hundred novels, including suspense, paranormal, historical, and mainstream Christmas fare. She is also the CEO of Slush Pile Productions, a recording company and production house for various charity events. Look her up at https://www.theoriginalheathergraham.com/.

Clay Stafford talks with Abbott Kahler “Advice for Writing True Crime”

Bestselling author Abbott Kahler joins Clay Stafford to discuss the intense research and writing process behind her new true crime book Eden Undone, sharing practical advice for writers of nonfiction and fiction alike—including the role of Scrivener, outlining, and writing techniques that bring history to life.

Abbott Kahler interviewed by Clay Stafford

I love nonfiction and fiction, and I had an opportunity to read Abbott Kahler’s new upcoming book, Eden Undone: A True Story of Sex, Murder, and Utopia, at the Dawn of World War II. Great title, of course; pulls everyone in. The amount of research Abbott put into this nonfiction book intrigued me, so I had to speak with her from her home in New York about how she put it all together. “So, Abbott, you've got all this research coming in. How do you make it useful and organize it rather than just putting it in a big Word document full of notes? I love research, probably too much, and my notes become a glorious mess that I must always go back and untangle. What's your organizational process? Anything you can share with me to make my process go smoother and more time-efficient?”

“I'm a big believer in outlining. I think it's essential. I use a tool called Scrivener that helps outline.”

“I’ve got it. I use it. But I’m not sure I use it well.”

“It allows you to move sections around, and it's searchable to find sources there. If there's a quote you want to remember, you can make sure it's in there, and you can find it just by searching. I think the outline for this book was 130,000 words…”

“The outline was 130,000 words?”

“Much longer than the finished book. The finished book is about 85,000 words, so I over-outline. I think it helps get a sense of narrative. I do a chronological outline, and I can see where I might want to move information and where I might want to describe someone differently. I think outlining extensively lets you see the story, making it much less daunting. Here you are with all this information, but if you have it formatted and organized, it will be much easier to tackle it piece by piece. You know, bird by bird, as Anne Lamott says. I highly recommend outlining for anybody who will tackle a big nonfiction project.”

“Well, even in fiction, there can also be a great amount of research depending upon the topic, setting, or even the personalities or careers of characters. Compare and contrast the writing of a nonfiction book versus that of a novel because you’ve done both.”

“Writing fiction was a surprise to me. I thought it was going to be easy. I thought, ‘Look at all this freedom I have. I can make my characters say and do whatever they want. If I want somebody to murder someone, goddammit, I am going to let them murder someone.’ You can't do that in nonfiction. That freedom was a lot of fun, and it was exhilarating, but it was also terrifying. I was always second-guessing my plot points. Does this twist work? Should there be another twist here? Is it too obvious? Do I have too many red herrings? Do I not have enough red herrings? And in nonfiction, you don't have those issues. What issue you have in nonfiction is that I am dumping information.”

“Of course, writers do that maybe too much sometimes in fiction, too.”

“One of the things I talk about with fellow nonfiction writers is how you can integrate backstory and history. You always have to give context. How do you integrate that context and still keep the momentum going forward, still keep the narrative moving, and still keep people invested in your story when you have to explain who Darwin was and what he did, you have to explain who William Beebe was and what he did, you have to explain what the Galapagos are, and what the history of the Galapagos is before you get into what happened there with these crazy characters. It’s different approaches and different skill sets.”

“I can see parallels, though, in both fiction and nonfiction here. Which do you like best?”

“It’s fun to go back and forth, and I think writing fiction teaches me a lot about nonfiction. You know, what you can get away with in nonfiction while still sticking to nonfiction. It allows you to be a little bit more inventive with your process in a way that's a lot of fun.”

“Interesting. Returning to Scrivener, do you start in Scrivener right from the beginning and start putting your notes in there?”

“I'll open Scrivener, and I'll start organizing by source. Say, I have Friedrich Ritter, a character in the book, and here's everything I know about Friedrich Ritter. I'll have a Friedrich Ritter file. Then I'll have a Baroness file and a Dore Strauch file, just getting into the characters in these separate ways. Their files are always accessible, and I can refer to them easily when I want to. ‘Oh, wait a minute. What did Dore say at that time? Oh, here it's in my Scrivener file on Dore.’ I draft in Word. I'm just an old-school person who uses Word to draft. I don't like Google Docs. I don't like drafting in Scrivener. I like Word because it lets you see the page count and feel like you're gaining momentum because the file is growing. It's a satisfaction that I think I—and probably many other people—need to see as they go through a big project like that.”

“I started with a typewriter, so for me, it seems to make sense.”

“I get you. I started with the word processor, which I don't even know if they make anymore. But you know, word processors were the rage back in college.”

“The narrative of a nonfiction book, then, is pretty much the same as that of a fiction book, in that you've got a traditional beginning, middle, and an end with all the conflicts, arcs, etc., that you find in fiction manuscript, correct?”