KN Magazine: Interviews

Clay Stafford talks with Paul Karasik on “How to Write a Graphic Novel”

Two-time Eisner Award winner Paul Karasik joins Clay Stafford to discuss how to write a graphic novel—how to think visually, collaborate with artists, and translate emotion into panels. A masterclass in visual storytelling from one of comics’ most insightful minds.

Paul Karasik interviewed by Clay Stafford

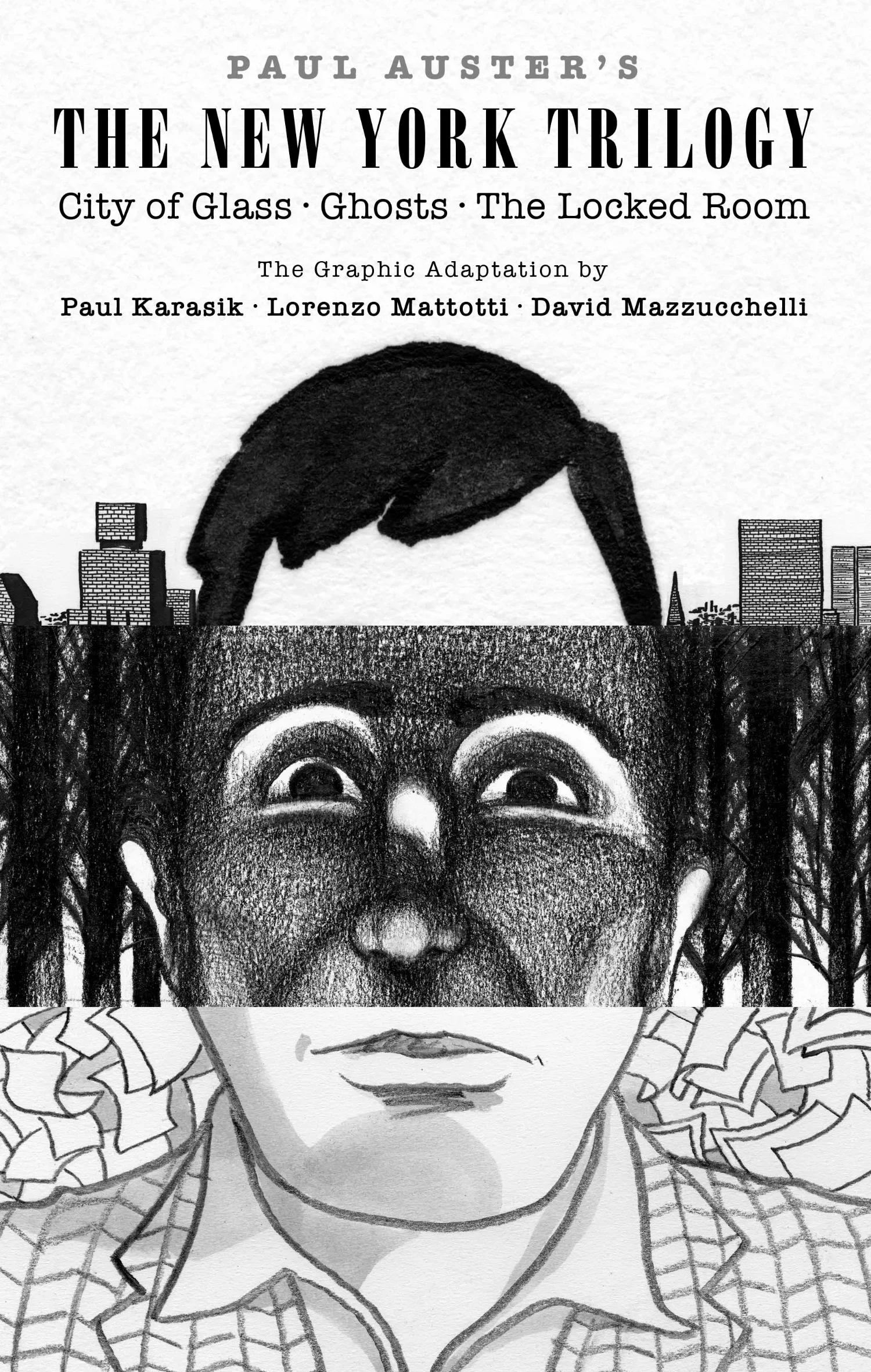

In the world of graphic storytelling, few figures bridge scholarship, craft, and creativity as seamlessly as Paul Karasik. A two-time Eisner Award winner, Karasik’s career has spanned from his early days as Associate Editor at RAW, the influential magazine founded by Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly, to adaptations of literary works that redefined what comics could do. His collaborations include The New York Trilogy, the acclaimed visual deconstruction How to Read Nancy (co-written with Mark Newgarden), and the memoir The Ride Together, written with his sister about growing up alongside their brother with autism.

Karasik is not simply an artist who draws or a writer who scripts. He’s a thinker who dissects how meaning is built through image, rhythm, and restraint. His teaching has influenced a generation of visual storytellers to approach comics as architecture: design, intention, and emotional subtext all working in tandem. In this conversation, I spoke with Paul about how to write a graphic novel: how to think in images, collaborate with artists, structure the visual page, and find the emotional heartbeat that turns panels into story. What follows is a masterclass in how words and pictures meet, and how purpose turns craft into art.

“Paul, let’s say I’ve decided to write a graphic novel, and I don’t know where to start. I’m not trying to sell it or anything; I just want to write it. I’ve heard that you need to think in scenes, not paragraphs. I’m not sure exactly what that means.”

“It’s more like screenwriting. Because it’s a visual medium, you really need to have a clear picture in your head of what everything looks like and how the space is laid out. Draw a little blueprint of what’s happening in any given scene so the characters move consistently through that space. The sofa is always to the left of the dining room table, or whatever. You need to have that visual sense.”

“So, in a way, the writer is the director, and the graphic realization comes from working with an artist, just as the filmic realization comes from working with a cinematographer. Is that a good analogy?”

“Absolutely. That’s a fine analogy. You’re engaging in a collaborative art. You’re working with an artist whom you may not have met yet, so you have to develop a relationship that allows for interpretation. Ideally, you find someone you can continue to work with. Ingmar Bergman is a great director, but Sven Nykvist was his cinematographer. Bergman’s movies always look like Bergman’s movies. You need that same strong sense of what the whole thing will look like and what its emotional core is. What’s the point? There’s the text, and then there’s the subtext. If you’re not addressing the subtext, you might as well be writing ad copy. One of the things I tell my students is that in a graphic novel, you don’t have a lot of space for dialogue. Your first draft can be verbose because you’re figuring out what the character needs to say. But once you know that, it has to be boiled down to ten words or less. You can’t have people going on for three paragraphs, or even three sentences. Two sentences max in a word balloon. There just isn’t that much space, and you don’t need it because the picture is doing the bulk of the work. So, two rules for dialogue: keep it short and keep it to the point. And every time a character speaks, that dialogue has to do two things. It has to reveal something about who that character is, and it has to move the plot forward. Even if a character says, ‘I don’t know,’ it should still be part of the story’s engine.”

“So, the old ‘show, don’t tell’ is really important in a graphic novel.”

“Absolutely. What you show and how you show it matters. Every panel is a composition, and the way it’s read, top to bottom, left to right, is storytelling.”

“When you’re writing it, you’re writing the panel descriptions as well as the dialogue, correct?”

“Every panel.”

“How do you determine, on a page, how many frames or panels you’re using? Does the writer decide that?”

“Here’s another really good reason to go to the bookstore and find a book that feels like it has the same kind of weight or tone as your own vision. Look at it. Does it have three tiers or four? How many panels per tier? How many words per page? Do the counting, and then model your writing after that. Even if your story isn’t the same genre, say, you’re writing something that’s going to be banned instead of a silly macho space fantasy that won’t be, it’s a good exercise.”

“The first and second stories of your New York Trilogy, they’re completely different. The first has smaller panels throughout, and the next has a large panel with a lot of writing underneath.”

“The very first lesson in my Graphic Novel Lab would be that form follows function. You have to understand what your story is about, and then figure out what the form should be. In the first book of The New York Trilogy, the layout is a nine-panel grid. Over the course of the story, the main character, who pretends to be a detective, becomes obsessed, loses his apartment, his past life, and eventually his mind. What that story is really about is the nature of fiction itself. If this coffee cup isn’t called a coffee cup, is it still a coffee cup? At the start, the layout is rigid, every page in that nine-panel grid. By the end, as the character unravels, the gutters between panels widen, the panels stop being drawn with a ruler, and they start to wiggle. As he loses his grip on reality, the comic itself becomes unglued until the panels fall off the page. That’s why it’s designed that way. In the second book, the layout looks more like an illustrated text, an image on top, words beneath. It’s still a detective story, but this one is really about reading fiction. The detective has never read anything in his life. When he tries to read Walden, he can’t. He only knows how to read for facts. So when we reach that moment in the book, the layout itself changes. The pages turn into comics panels, forcing the reader to experience a different kind of reading. Then we switch back again. The format shifts to underscore the subtext: you can read passively, or we can make you read actively.”

“There’s not a lot of space. You’ve got action, a little dialogue, and you have to keep internal monologue to a limit, don’t you?”

“Not necessarily. Thought balloons and narrative blocks can serve as exposition when needed, but everything should support the story. You need to know your story, your plot, and your subtext before designing your comic. It may sound intimidating, but once you learn to think like a cartoonist, it becomes natural. That’s what I teach: a way of thinking.”

“Let’s talk about setting.”

“The setting and environment are essential. In the first book of The New York Trilogy, New York City is as much a character as the protagonist. In the second book, less so. By the third, the story hardly mentions New York at all, yet you still know where you are. So, yes, establish the world early. Don’t make the reader guess whether they’re in a space capsule or a time capsule. Do them a favor.”

“As a writer who writes for directors, I’m always careful not to cross that creative line. For the writer sitting at the desk putting this together, what’s the line they shouldn’t cross when working with a graphic artist?”

“Every collaboration is different. Think again of Bergman and Nykvist. At first, there was probably a lot of back-and-forth. But once a relationship is built, each trusts the other’s instincts. For the books I’ve worked on, I’ve done the sketches and scripts myself because I can draw. Both artists I’ve worked with collaborated closely to bring those sketches to life and then did the finished art. The best relationships are built on mutual respect. You find an artist whose style fits your vision, and you trust each other.”

“You’ve mentioned that your projects often find you, rather than the other way around. As a parting thought, can you talk about that passion? What turns a project from work-for-hire into something driven by obsession?”

“I have a peculiar career because I don’t do just one thing. I adapted Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy, co-wrote How to Read Nancy with Mark Newgarden, and wrote a memoir with my sister about growing up with our brother, who had autism, The Ride Together. None of these were projects I consciously chose. They demanded to be made. When I try to invent something just to invent it, I can tell when it’s hollow. The real ones insist on being created. It’s instinctual. I don’t have a choice. It’s compulsion, obsession. That’s how I’m built. Don’t start a graphic novel thinking you’ll sell it immediately, and don’t do it just because you liked Spider-Man as a kid. Do it because you can’t possibly do anything else. It’s what you were meant to do.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of the Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference, Killer Nashville Magazine, and the Killer Nashville University streaming service. Subscribe to his newsletter at https://claystafford.com/.

Two-time Eisner Award winner Paul Karasik began his career as the Associate Editor of Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly’s RAW magazine. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The New Yorker.

https://www.paulkarasikcomics.com/

Author photo credit: Ray Ewing

“A Casual Conversation with Susan Isaacs”

In this informal and delightful follow-up conversation with bestselling author Susan Isaacs, we chat about writing description, plotting mysteries, working with ADHD, and how building a fictional series can feel like creating a second family. A refreshing reminder of why writers write—and why conversations like this matter.

Susan Isaacs interviewed by Clay Stafford

I had a wonderful opportunity to just chat with bestselling author and mystery legend, Susan Isaacs, as a follow-up to my interview with her for my monthly Writer’s Digest column. It was a wonderful conversation. I needed a break from writing. She needed a break from writing. Like a fly on the wall (and with Susan’s permission), I thought I’d share the highlights of our conversation here with you.

“Susan, I just finished Bad, Bad, Seymore Brown. I loved it. And I now have singer Jim Croce’s earworm in my head.”

“Me, too.” She laughed.

“I love your descriptions in your prose. Right on the mark. Not too much, not too little.”

“Description can be hard.”

“But you do it so well. Any tips?”

“Well, I’ll tell you what I do. Two things. First, I see it in my head. I’m looking at the draft, and I say, ‘Hey, you know, there’s nothing here.’”

I laugh. “So, what do you do?”

“Well in Bad, Bad, Seymore Brown, the character with the problem is a college professor, a really nice woman, who teaches film, and her area of specialization is big Hollywood Studio films. When she was five, her parents were murdered. It was an arson murder, and she was lucky enough to jump out of the window of the house and save herself. So, Corie, who’s my detective, a former FBI agent, is called on, but not through herself, but through her dad, who’s a retired NYPD detective. He was a detective twenty years earlier, interviewing this little girl, April is her name, and they kept up a kind of birthday-card-Christmas-card relationship.”

“And the plot is great.”

“Thanks, but in terms of description, there was nothing there. But there were so many things to work with. So, after I get that structure, I see it in my head, and I begin to type it in.”

“The description?”

“Plot, then description.”

“And you mentioned another thing you do?”

“Research. And you don’t always have to physically go somewhere to do it. I had a great time with this novel. For example, it was during COVID, and nobody was holding a gun to my head and saying ‘Write’ so I had the leisure time to look at real estate in New Brunswick online, and I found the house with pictures that I knew April should live in, and that’s simply it. And I used that house because now April is being threatened, someone is trying to kill her twenty years after her parent’s death. Though the local cops are convinced it had nothing to do with her parents’ murder, but that’s why Corie’s dad and Corie get pulled into it.”

“So basically, when you do description, you get the structure, the bones of your plot, and then you go back and both imagine and research, at your leisure, the details that really set your writing off. What’s the hardest thing for you as a writer?”

“You know, I think there are all sorts of things that are hard for writers. For me, it’s plot. I’ll spend much more time on plot, you know, working it out, both from the detective’s point-of-view and the killer’s point-of-view, just so it seems whole, and it seems that what I write could have happened. For me, I don’t want somebody clapping their palm to their forehead and saying, ‘Oh, please!’ So that’s the hard thing for me.”

“You’ve talked with me about how focused you get when you’re writing.”

“Oh, yes. When you’re writing, you’re really concentrating. We were having work done on the house once and they were trying to do something in the basement, I forget what it was. But there was this jackhammer going, and I was upstairs working. It was when my kids were really young and, you know, I had only a limited amount of time to write every day, and so I was writing and I didn’t even hear the jackhammer until, I don’t know, the dog put her nose or snout on my knee and I stopped writing for a moment and said, ‘What is that?’ and then I heard it.”

“But it took your dog to bring you out of your zone. Not the jackhammer.”

“You get really involved.”

“Sort of transcending into another universe.”

“The story pulls you in. The weird thing is that I have ADD, ADHD, whatever they call it. I know that now, but I didn’t know that then, back when the jackhammer was in the basement. In fact, I didn’t know there was a name for it. I just thought, ‘This is how I am.’ You know, I go from one thing to the next. But people with ADHD can’t use that as an excuse not to write because you hyper-focus.”

“That’s interesting.”

“You don’t hear the jackhammers.”

“So things just flow.”

“Well, it’s always better in your head than on the page,” she says, “as far as writing goes.”

“I’d love to see your stories in your head, then, because your writing is great. As far as plotting, the book moves along at a fast clip. I noticed, distinctly, that your writing style is high with active verbs. Is that intentional or is that something that just comes naturally from you?”

“I think for me it just happens. It’s part of the plotting.”

“Well, it certainly moves the story forward.”

“Yes, I can see it would. But, no, I don’t think ‘let me think of an active verb’. You know,” she laughs, “I don’t think it ever occurred to me to even think of an active verb.”

“That’s funny. We’re all made so differently. I find it fascinating that, after all you’ve published, your Corie Geller novel is going to be part of the first series you’ve ever written. Everything else has been standalones.”

“Yes. I’m already writing the next book. Look, for forty-five years, I did mysteries. I did sagas. I did espionage novels. I did, you know, just regular books about people’s lives. But I never wrote a series because I was afraid I after writing one successful mystery, that I would be stuck, and I’d be writing, you know, my character and compromising positions with, Judith Singer goes Hawaiian in the 25th sequel. I didn’t want that. I wanted to try things out. So now that I’ve long been in my career this long, I thought I would really like to do a series because I want a family, another family.”

“Another family?”

“I mean, I have a great family. I have a husband who’s still practicing law. I have children, I have grandchildren, but I’m ready for another family.”

“And this series is going to be it?”

“It’s not just a one-book deal. I wanted more. So, I made Corie as rich and as complicated and as believable as she could be. It’s one thing to have a housewife detective. It’s another to have someone who lives in the suburbs, but who’s a pro. And she’s helped by her father, who was in the NYPD, who has a different kind of experience.”

“And that gives you a lot to work with. And, in an interesting way, at this stage of your life, another family to explore and live with.” I look at the clock. “Well, I guess we both need to get back to work.”

“This has been great. When you work alone all day, it’s nice to be able to just mouth off to someone.”

We both laughed and we hung up. It was a break in the day. But a good break. I think Susan fed her ADHD a bit with the distraction, but for me, I learned a few things in just the passing conversation. Writers are wonderful. If you haven’t done it today, don’t text, don’t email, but pick up the phone and call a writer friend you know. I hung up the phone with Susan, invigorated, ready to get back to work. As she said, it’s nice to be able to just mouth off to someone. As I would say, it’s nice to talk to someone and remember that, as writers, we are not alone, and we all have so much to learn.

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer and filmmaker and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. https://claystafford.com/

Susan Isaacs is the author of fourteen novels, including Bad, Bad Seymour Brown, Takes One to Know One, As Husbands Go, Long Time No See, Any Place I Hang My Hat, and Compromising Positions. A recipient of the Writers for Writers Award and the John Steinbeck Award, Isaacs is a former chairman of the board of Poets & Writers, and a past president of Mystery Writers of America. Her fiction has been translated into thirty languages. She lives on Long Island with her husband. https://www.susanisaacs.com/

Author Amulya Malladi on “Research: Doing It, Loving It, Using It, and Leaving It Out”

In this informal and delightful follow-up conversation with bestselling author Susan Isaacs, we chat about writing description, plotting mysteries, working with ADHD, and how building a fictional series can feel like creating a second family. A refreshing reminder of why writers write—and why conversations like this matter.

Amulya Malladi interviewed by Clay Stafford

“I’m talking today with international bestselling author Amulya Malladi about her latest book A Death in Denmark. What I think is fascinating is your sense of endurance. This book—research and writing—took you ten years to write.”

She laughs. “You know, it was COVID. We all didn’t have anything better to do. I was working for a Life Sciences Company, a diagnostic company, so I was very busy. But you know, outside of reading papers about COVID, this was the outlet. And so that’s sort of how long it took to get the book done. I had the idea for a long time. I needed a pandemic to convince me that I could write a mystery.”

“Which is interesting because you’d never written a mystery before. Having never worked in that genre, I’m sure there was a learning curve there for you.”

“A lot of research.”

“You love reading mysteries, so you already had a background in the structure of that, but what you’ve written in A Death in Denmark is a highly focused historical work. It’s the attention and knowledge of detail that really made the book jump for me. Unless you’re a history major with emphasis on the Holocaust and carrying all of that information around in your head, you’re going to have to find factual information somewhere. How did you do that?”

“Studies.”

“Studies?”

“You’ll need a lot of the studies that are available. Luckily, my husband’s doing a Ph.D. He has a student I.D., so I could download a lot of studies with it. Otherwise, I’d be paying for it. Also, I work in diagnostic companies. I read a lot of clinical studies. So these are all peer-reviewed papers that are based on historic research, and they are published, so that is a great source, a reference.”

“But what if you don’t have that access?”

“You can go to your library and get access to it as well. If you’re looking for that kind of historic research, this is the place to go.”

“Not the Internet? Or books, maybe?”

“Clinical studies and peer-reviewed papers, peer-reviewed clinical studies, they’re laborious.”

“And we’re talking, for this book, information directly related to the historical accuracy of the Holocaust and Denmark’s involvement in that history?”

“You have to read through a lot to get to it. And it’s not fiction. They’re just throwing the data out there. But it’s a good source, especially for writers because we need to know about two-hundred-percent to write five-percent.”

“The old Hemingway iceberg reference.”

“To feel comfortable writing that five, you need to know so much more. I could write actually a whole other book about everything that I learned at that time. And that is a good place to go. So I recommend going and doing, not just looking at, you know, Wikipedia, and all that good stuff, but actually going and looking at those papers.”

“Documents from that time period and documents covering that time period and the involvement of the various individuals and groups.”

“When you read a paper, you see like fifteen other sources for those papers, and then you can go into those sources and learn more.”

I laugh this time. “For me, research is like a series of rabbit holes that I find myself falling into. How do you know when to stop?”

“The way I was doing it is I research as I write, and I do it constantly. You know, simple things I’m writing, and I’m like, ‘Oh, he has to turn on this street. What street was that again? I can’t remember.’ I have Maps open constantly, and I know Copenhagen, the city, very well. But, you know, I’ll forget the street names. That sometimes takes work. I’m just writing the second book and I wanted Gabriel Præst, my main character and an ex-Copenhagen cop, to go into this café and it turned into a three-hour research session.”

“Okay. Sounds like a rabbit hole to me.”

“You’ve got to pull yourself out of that hole, because, literally, that was one paragraph, and I just spent three hours going into it. And now I know way too much about this café that I didn’t need to know about. Again, to write that five-percent, I needed to know two-hundred percent. I am curious. I like to know this. So suddenly, now I have that café on my list because we’re going to Copenhagen in a few weeks, and I’m like, ‘Oh, we need to go check that out.’”

“So you’re actually doing onsite research, as well?”

“Yes. I use it all. I think as you write you will see, ‘Okay, now I got all the information that I need.’

“And then you write. Research done?”

“No. I was editing and again I was like, ‘Is this really correct? Did I get this information correct? Let me go check again.’”

“Which is why, I guess, your writing rings so true.”

“I think it is healthy for writers to do that, especially if you’re going to write historical fiction or any kind of fiction that requires research. Here’s the important thing. I think with research, you have to kind of find the source always. You know? It’s tempting to just end up in Wikipedia because it’s easy. You get there. But you know, Wikipedia has done a pretty decent job of asking for sources, and I always go into the source. You know you can keep going in and find the truth. I read Exodus while I lived in India. One million years ago, I was a teenager, and I don’t know if you’ve read Leon Uris’s Exodus, but there’s this famous story in that book about the Danish King. When the Germans came, they said, ‘Oh, they’re going to ask the Jews to wear the Star of David,’ and the story goes, based on Exodus, that the king rode the streets with the Star of David. I thought that was an amazing story. That was my first introduction to Denmark, like hundreds of years before I met my husband, and that story stayed with me. And then I find out it’s not a true story. You know? You know, Marie Antoinette never said ‘Let them eat cake.’ And so it was like, ‘Oh.’”

“Washington did not chop down the cherry tree.”

“No, and the apple didn’t fall. I mean, it’s simple things we do that with, right? With Casablanca, it’s like you said, you know, ‘Play it again, Sam.’ And she never said that. She said, ‘Play it.’ And you realize these become part of the story.”

“Secondary sources then, if I get what you’re saying, are suspect.”

“Research helps you figure out, ‘Okay, that never happened.’”

“When you say that you’re writing, and you’re incorporating the research into your writing sometimes you can’t, you’re not in a spot where the research goes into it. So, how do you organize your research that you’re not immediately using?”

“I don’t do that. I’m sure there are people who do that well. I’m sure there are people who are more disciplined than I am. I’m barely able to block my life. I mean, it’s hard enough, so you know if I do some research, I know there are people who take notes. I have notes, but those are the basics. ‘Oh, this guy’s name is this, his wife is this, he’s this old, please don’t say he’s from this street, he’s living on this street…’ Some basics I’ll have, so I can go back and look. But a lot of the times I’m like, ‘What was this guy’s husband doing again?’ I have to go find it. I won’t read the notes in all honesty, even if I make them. So for me, it’s important to go in and look at that point.”

“And this is why you write and research at the same time.”

“And this is why maybe it’s not the best way to do the research. It takes longer, like I said, you spend three hours doing something that is not important, but hey, that was kind of fun for me. I was curious to remember about Dan Turéll’s books, because I hadn’t read them for a while.”

“Some writers don’t like research. You like research. And for historicals, there’s really no way around it, is there?”

“I take my time and I think I really like the research. I have fun doing it.”

“Does it hurt to leave some of the research out?”

“Oh, my God, yes. My editor said, ‘You know, Amulya, we need the World War II stuff more.’ I’m like, ‘Oh, really? Watch me.’ So I spend all this time and I basically wrote the book that my character, the dead politician, writes.”

“This is an integral part of the story, for those who haven’t read the book.”

“I wrote a large part of that book that she is supposed to have written and put it in this book. I put in footnotes.”

“Footnotes?”

“My editor calls me and she’s like, ‘I don’t think we can have footnotes and fiction.’ I’m like, ‘Really?’ And she goes, ‘You know, you can make a list of all of this and put it in the back of the book. We’ll be happy to do that. But you can’t have footnotes.’ I felt so bad taking it out because this was really good stuff. You know, these were important stories.”

“So it does hurt to leave these things out.”

“I did all kinds of research. I read the secret reports, the daily reports that the Germans wrote, because you can find pictures of that. I kind of went in and did all of that to kind of make this as authentic as possible, and then she said, ‘Could you please, like make it part of the book, and not as…’ She’s like ‘People are going to lose interest.’ So yeah, it does hurt. It really didn’t make me happy to do that.”

“You reference real companies, use real restaurants, use real clothing, use real drinks. You use real foods. Do you have some sort of legal counsel that has looked over this to make sure nobody is going to sue you for anything you write? Or how do you protect yourself in your research?”

“When I’m being not-so-nice about something, I am careful. I have not heard anything from legal. Maybe I should ask tomorrow. I think Robert B. Parker said this in an interview once: ‘If I’m going to say something bad about a restaurant, I make the name up.’”

“Circling back, you do onsite research, as well.”

“Oh, yeah. I’ve been to Berlin several times, so I know the streets of Berlin. I know this process. I know what they feel like. It’s easier to write about places you’ve been to, but the details you will forget. Even though I know Copenhagen very well, I still forget the details. ‘What is that place called again? What was that restaurant I used to go to?’ And then I have to go look in Maps, and find, ‘Ah, that’s what it’s called here. How do they spell this again?’ But I think, yes, from a research perspective, if you are wanting to set a whole set of books somewhere, and if you have a chance to go there, go. Unless you’re setting a book in Afghanistan, or you know, Iraq, then don’t go. Because I did set a book partly in Afghanistan and I remember I talked to a friend of mine. She’s a journalist for AP and she said, ‘Oh, you should come to Kabul.’ And I’m like, ‘No, I don’t think so, just tell me what you know so I can learn from that and write it.’ She’s like, ‘You’ll have a great time on it.’ And I said, ‘I will not have a great time. No, not doing that.’ But I think, yes…”

“When it comes to perceived safety, you’re like me, an armchair researcher. Right?”

“Give me a book. Give me a clinical study. Give me a peer-reviewed paper, I’ll be good.”

“What advice do you have for new writers?”

“Edit. Edit all the time. I’ve met writers, especially when they are new, they say things like, ‘Oh, my God! If I edit too much, it takes the essence away. I always say, ‘No, it just takes the garbage away.’ Edit. Edit, until you are so sick of that book. Because, trust me, when the book is finished and you read it, you’ll want to edit it again because you missed a few things. I tell everybody, ‘Edit, edit, edit. And don’t fall in love with anything you write while you’re writing it because you may have to delete it.’ You know, you may write one-hundred pages and realize, I went on the wrong track and now I have to go delete it.”

“And take out the footnotes.”

“Yeah, and take out the footnotes.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, literary theorist, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. https://claystafford.com/

Clay’s book links: https://linktr.ee/claystafford

Amulya Malladi is the bestselling author of eight novels. Her books have been translated into several languages. She won a screenwriting award for her work on Ø (Island), a Danish series that aired on Amazon Prime Global and Studio Canal+. https://www.amulyamalladi.com/

Amulya’s book link: https://linktr.ee/amulyamalladi

Submit Your Writing to KN Magazine

Want to have your writing included in Killer Nashville Magazine?

Fill out our submission form and upload your writing here: