KN Magazine: Interviews

Clay Stafford Interviews… Sara Paretsky: “Making A Difference”

Sara Paretsky, trailblazing creator of V.I. Warshawski and founder of Sisters in Crime, talks with Clay Stafford about writing with purpose, amplifying unheard voices, and navigating complex social issues without losing narrative power—or hope.

Sara Paretsky interviewed by Clay Stafford

Don Henley sang about wanting to get “to the heart of the matter.” In this interview, I did. Sara Paretsky is a legend in detective fiction but also a champion for the rights of those who don’t have a voice. I spoke with her and found her as compassionate and passionate as my impressions of her were before we met. What struck me the most before the interview was her concern for others. How people incorporate that concern to make the world truly a better place without the preachiness that sometimes comes from pedantic writing is what I sought to investigate with her.

“Sara, it's not difficult to read your work and see where you might stand on things. Do you think it is necessary or even an obligation for writers to include social issues in their work?”

“I think writers should write what is in them to write. I don't sit down wanting to tackle social issues.”

“They’re there, though, so they just come out?”

“It's just they inform my experience and how I think. And it's not even what I most want to read. I most want to read someone who writes a perfect English sentence with an exciting story. That's what I care about. You read things you're in the mood to read, which changes at different points in your life. When I was about ten, my parents gave me Mark Twain's recollections of Joan of Arc to read. My parents felt that I had too intense a personality and that I was always going to suffer in life unless I dialed it back. They wanted me to see the fate that awaited too fierce girls. They get burned at the stake. So, I read this book, and it did not make me wish to dial back my intensity. It made me wish I could have a vision worth being burned at the stake for. That is just my personality, and that's why these issues keep cropping up in my books.”

“I don't know if it's even true, but one of my favorite Joan of Arc stories is that she went to those in charge and wanted the army to go, and they said, ‘They won't follow you. You're a woman,’ and she said, ‘Well, I won't know because I won't be looking back.’”

“Oh, God! I love it!”

“I think that's incredible. And, of course, they still burned her at the stake. That was a fantastic way of looking at that vision, which sounds like what you were talking about.”

“I’ve got hearing aids, and I keep hoping to get messages. I hope St. Catherine and St. Michael will start telling me what to do.”

“Some people are putting tin foil over their heads to stop the messages from coming in. You're hoping they will arrive.”

“You heard it here first when you want to come see me in the locked ward.”

“You said you wanted to write your first book, if I've got this right, to change the way women are portrayed in detective literature, and the gamut of portrayal at the time ran from sex objects to victims of formidable forces, women who must be judged because of their moral bankruptcy, or those who needed to be rescued by Harrison Ford. Do you feel you achieved that regarding how women are portrayed today?”

“Oh, I think not. What I think changed is that the roles for women became much more diverse, reflecting how society was changing. When Sue Grafton and I started, we were on the crest of a wave of the world looking at women differently. Lillian O'Donnell was in a previous generation of women writers, and she had a woman who was a New York City transit police officer solving crimes. But she was writing at a time when people weren't ready to see women taking on these more public roles. I published my first book the year Chicago let women be regular police officers instead of just matrons at the Women's Lockup and the Juvie Lockup. People don't remember this, but there were not exactly riots, but wives of patrol officers were storming the precincts, demanding that women not be allowed in patrol cars with their husbands because they knew that either they would seduce their husbands, or they weren't strong enough to provide backup for their husbands. We don't remember that struggle because we take it for granted now. But I was publishing my first book when all those items were in the stew. Can women do this? Should women do this? And now, there's still a lot of pushback, but nobody questions whether a woman should be in the operating room, or on the Supreme Court, or doing these kinds of things. So, in that way, I was part of a change, for what I think is a change for good. At the same time, I can't speak to why, but I feel like there's a lot of contemporary crime fiction where people are almost in a one-downmanship struggle to use the most graphic, grotesque violence. I know it's unfair to pick on the dead rather than on the living: The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. I'm, of course, honored that Stieg Larsson considered me an influence on him. Still, every detail of the sexual assault and abuse committed on Lisbeth Salander is described in exquisite detail. Then, when she seeks revenge, all of that is described in exquisite detail. The use of violence has become almost pornographic. But also, you know, V.I. and Kinsey Millhone became detectives out of a sense of possibility, joy, and problem-solving. But there's a tremendous amount of victimization of women, and it's acceptable for them to take an active role in fighting back against being victims. But we're not seeing a lot of women going into this work just because they want to. There is always a reason, and it must be a victim reason, in way too much fiction as I'm reading it, and I find that depressing and disturbing.”

“But when you started writing, and tell me if I'm misquoting you, you said you wanted to change the narrative about women in fiction.”

“Right.”

“I noted you didn't say detective fiction, but you said, ‘I want to change the narrative about women in fiction,’ and some would say you did achieve that.”

“I think that does me more honor than I deserve. I was one of the voices that helped make that happen, and I think we did.”

“This is a difficult question and something I always tell my children. I was like, ‘Okay, to argue a point, you must be able to argue both sides equally well. And then you know the issues.’”

“Great advice. I wonder if I could do that?”

“It's worked well for the kids. But this is a difficult question for those with strong opinions. At this moment, we humans seem to be a bit divided. How do you feel about authors taking social stands on issues with the opposite allegiance to where you or I might stand?”

“I think they should be boiled and oiled and have their carcass– No.”

“I don't think that's true. I don't think you believe that at all.”

“I don’t believe it. I'm wading into controversial waters here, but I'm a Jew. Since October seventh, I feel like my brain has been split, not just in half, but maybe in six or seven pieces because I'm totally against the violence against Palestinians in Gaza. I'm totally against the relief and joy that some Americans expressed watching live streaming of Israeli women being raped and mutilated. I'm totally for some things and totally against some things, and there are like maybe eight different ways you could segment yourself on Israel, Hamas, Palestine, Gaza, West Bank Settlers, and U.S. policy. That's an issue where everyone has a strong opinion, except for someone like me, who is fragmented in the middle. And so, I'm listening to all of these, and I think writers who want to hold forth on this are bolder and braver than I am, but it also is an opportunity for me to get exposed to many different viewpoints. And in that sense, yeah. Great, everyone who feels they know enough to speak about it, or even if they don't know enough, is speaking about it. I know that I would not be a person who could write an empathic, believable story about someone who was opposed to women's access to reproductive health. But if that's where your head is, you should write it, and maybe you can create a sympathetic character that would help me understand why you have those views that are so repugnant to me.”

“Regardless of the perspective of one, literature is a powerful sword, as we know, and people read things and, maybe like your parents were talking about with your Joan of Arc, it's going to subdue you a bit. But no, it made you blossom. And so, you never know which way literature will lead you to look at something and then go, ‘Wait, let me think about this a little more.’ I think differing opinions do tend to do that.”

“Yes, and if you have one monolithic opinion, you are doomed. You need to hear many voices of a story. It's only tangentially connected to this, but Enrico Fermi, the giant physicist of the 20th century, was the person who brought my husband to the University of Chicago. My husband was quite a bit older than me, and he died five years ago, and I still miss him every day. But that's beside the point. When Fermi was dying, he died of esophageal cancer around 1955. A young intern came into his hospital room and tried to talk to him cheerfully about his prospects and the future. And Fermi said, ‘I'm dying, and what you need to learn as a young doctor is how to talk to people about the fact that they're dying.’ This is all in this doctor's memoir. This doctor published this six or seven years ago, at the end of his career, and he had asked Fermi how he could have such a stoical outlook. Fermi was reading Tolstoy's short stories, “The Death of Ivan Ilyich” and other stories, and Fermi said, ‘You go home and read “The Death of Ivan Ilyich,” and you will learn how to talk to your patients about death and dying.’ The doctor said, ‘Yes, I went and did that, and it was the most important part of my medical education.’”

“Literature is powerful. So why did you lead the charge – and I think I know this, but I'm asking – why did you lead the charge to create Sisters in Crime. How did that come about?”

“In March of 1986, Hunter College convened what I think was the first-ever conference on women in the mystery field: writers, readers, publishers, editors. I had published two books, and they asked me to speak, which was exciting. I was on panels with people I'd been reading for a long time, including Dorothy Salisbury Davis, who became a close friend. Because I lacked impulse control, I made some strong statements. These generated a lot of discussion, and I started hearing from other women around the country. Sue Grafton and I were fat, dumb, and happy. We published our books. We got a lot of great reviews. We didn't understand the industry, or I didn't. Maybe Sue did. She was smarter than me in many ways. But women who were being asked questions like, ‘What do you do when your kitty cat gets on your keyboard,’ or ‘Isn't it nice that you have a hobby so that you're not bothering your husband when he comes home from a hard day's work?’ You know, just lots of ugly stuff. The great civil rights lawyer, Flo Kennedy, said, ‘Don't agonize, organize.’ So, at the Bouchercon in Baltimore in October of 1986, I sent letters to everyone I had heard from and the women I knew, twenty-six people, to see if women wanted to get together to form an advocacy organization. I said, ‘If you do, we’ll work; if you don't, we'll shut up and stop crying about it.’ Everybody was on board with it, and our first project was our book review monitoring project because Sue and I were getting all these reviews. Most women were not getting reviewed at all. Sue and I were getting reviewed because we were doing something that was being perceived as male. We had privatized. We were doing something in that Raymond Chandler, Ross Macdonald, John MacDonald tradition. And so, we connected with male readers and reviewers. But women who are doing things outside that: cops, so-called cozies, domestic crime. They were not getting reviewed. Our first project was to get numbers on that. Because if you're not getting reviewed, libraries will not buy you. And they were, in those days, the biggest buyer of midlist books. And bookstores don't know you exist. So, with the help of Jim Wang at the Jude Review, we got a list of 1,100 crime thriller mystery books published in 1986 and then worked hard. We looked at two hundred newspapers and magazines and looked at the reviews, and we found that a book by a man was seven times more likely to be reviewed than a book by a woman. We figured, ‘God. Maybe men write twice as well as we do, but not seven times as well.’ So, we started just going to bookstores and libraries. Sharon McCrumb, Carolyn Hart, and Linda Grant, I think it was, put together books in print by women writers. We didn't want to go headlong against the industry because we needed the industry. We wanted to educate people. Sisters grew out of that and has been essential as a place of support. Of course, some men belong, and it's been a template. Writers of Color—I don't have the exact name right—are advocating, so you're starting to see many more mysteries by writers of color than you would have seen ten years ago. This advocacy makes a difference, and it makes a difference not by being confrontational but by being educational and showing publishers, booksellers, and so on that there's a market for these characters. People want to read about them. We were going back to your previous question about regional characters. Now, we're down at the grassroots of where stories come from. And we see that a story speaks to people regardless of race, creed, or place of national origin. Some days, I feel so much despair I can hardly get out of bed, but when I think of the possibility that readers and writers have of exploring so many different voices and places, it's like, yeah, this is a brave new world.”

“What advice do you have for writers of today?”

“If you're writing for the market, you may hit it lucky, but the market is such a fickle place that by the time you finish your book, it will be interested in something else. You write what's in you to say and do it the best way you can. One thing I don't have that I wish I had in my own life is that I don't have a reading group, and I don't have a first reader now that my husband is gone. I have not found the right person, or maybe I haven't even looked. But you need a sounding board, even if it's just one person. Your head is an echo chamber, so get feedback but also stay true to your voice and vision. Balance the two. It's like you were saying, can you have a sympathetic voice opposite your position? You may love your prose so much that you don't want to alter one word. There's one important writer you're not allowed to edit today, and I'm like, ‘Oh, sweetheart, I'd read you more often if you'd let someone cut about 30% of that deathless prose.’”

“You've been called ‘the definition of perfection’ by the Washington Post.”

“Yeah, right.”

“And ‘a legend’ by people such as Harlan Coben, and for your work ‘the best on the beat’ by the Chicago Tribune and others, and the list goes on and on and on. How does that make you feel? How does it feel to be labeled as ‘perfection’?”

“That's an impossible bar to reach and go over.”

“But you have that reputation.”

“Yeah, well, you know…”

“And you've bumbled well into it, right? Let me ask you this. Other people think of you as a legend for numerous reasons. Whether it's Sisters in Crime, your advocacy in your personal life, your writing, or the influence your writing has had, what would Sarah Paretsky like to be remembered for?”

“I'd like to be remembered for telling stories that cheered people up.”

“That's a wonderful thing.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. https://claystafford.com/

Sara Paretsky revolutionized the mystery world with her gritty detective V.I. Warshawski in Indemnity Only, followed by twenty V.I. novels, her memoir, two stand-alone novels, and short stories. She created Sisters in Crime, earning Ms. Magazine’s Woman of the Year. She received the British Crime Writers’ Cartier Diamond Dagger and Gold Dagger. https://saraparetsky.com/

Clay Stafford talks with Author Tom Mead on “Writing Locked Room Mysteries”

Clay Stafford sits down with locked-room mystery author Tom Mead to discuss the intricacies of writing seemingly impossible crimes, the influence of stage magic and the Golden Age of detective fiction, and how modern readers can engage with this classic and complex genre.

Tom Mead interviewed by Clay Stafford

I stumbled upon Tom Mead’s latest locked-room mystery from my friend Otto Penzler and immediately loved it. I knew I had to talk to Tom about it, as it was probably one of the best I’ve read in a long while. Tom and I got together electronically, me from Tennessee, U.S., and him from Derbyshire, U.K. The modern age of technology is not just fantastic for meetings such as this, but it also fosters a sense of global community, allowing us to get to know others face-to-face across continents. I was curious to know how, in the modern age, technology has affected what is known as the locked room mystery simply because these types of mysteries are fascinating intellectual puzzles, and modern forensics are straightforward (and often more quickly derived) facts. This interview ran long. Part of it has previously appeared in my monthly Writer’s Digest column, but the full interview, about four times the length of the Writer’s Digest version, constitutes our entire conversation. I learned so much from Tom that I felt other mystery writers might gain the same things I did by hearing Tom’s conversation in full. “Tom, for those unfamiliar with a locked room mystery, can you explain that to us?”

“Yes, absolutely. The term refers to a sub-genre of the classic puzzle mystery, or the whodunnit, emphasizing a seemingly impossible crime. So, in other words, a crime that physically could not have taken place. Hence, the imagery of the locked room. Locked room mysteries are a rarefied sub-genre because, by their nature, they are complex and convoluted creations. They’re structured like a puzzle, but there’s also an emphasis on the atmosphere and a kind of eeriness about them because there’s the appearance of something supernatural having taken place. But, of course, the solution is always rational and earthly. The locked room mystery became popular during the Golden Age of detective fiction between the World Wars. Many great authors tackled the genre, but my favorite is John Dickson Carr, the acknowledged master of the locked room mystery. I started writing locked rooms as a kind of tribute to him, and I look at them as a kind of literary magic trick, if you like. It’s all about misdirection and creating the appearance of the impossible.”

“Well, you had me trying to beat you at this mystery, and I have to say I did not.”

“Well, that’s good. That’s part of the fun, of course. A great thing about Golden Age detective fiction—something that appeals to me as a reader—is this idea of the intellectual game and the challenge to the reader. Ellery Queen was particularly good at that sort of thing and would often include a literal challenge to the reader, wherein the author would sort of step in, address the reader directly, and say, “All the clues are there. They’ve been hidden throughout the text for you to spot. Can you solve the mystery before the detective?” And so, I thought it would be fun to incorporate a literal challenge to the reader into my Spector mysteries. So again, it’s all part of the tribute to the Golden Age, but also having a bit of fun with the reader, and just playing up that puzzle aspect of the mystery.”

“Well, my wife said, ‘How is it?’ because I read a lot of books, and I said, ‘This is very good, but I am not sure how he’s going to pull this off,’ and I’m not giving anything away, because we’ve got a picture on the cover here, how did this person get in this boat? And that was the one that kept throwing me. And you don’t reveal until the very end, almost, how that happened. And so, I’m going, ‘Is he going to play fair? Is he going to answer how this boat shows up in here?’ So anyway, you did well in wrapping everything up.”

“Thank you very much. And yes, thank you for saying that about the boat puzzle. That was the one that I had the most fun with. It’s the most elaborate. In that respect, it’s a tribute to the Japanese locked room mystery or traditional Japanese mystery because there’s been a recent glut of translations of classic Japanese mysteries. I’ve had great fun delving into them. They are remarkably complex, even by the standards of Golden Age detective fiction, and some of the clever devices, techniques, tricks, and gimmicks that writers like Seishi Yokomizo have come up with are great and help to stimulate my imagination as a writer as well as a reader. I think that’s also partially a tribute to the Japanese mystery tradition.”

“You’ve been citing different cultures and countries. Locked room is global in every type of culture.”

“Yeah, I mean, the appeal of mystery fiction generally is universal, I think, and there have been numerous anthologies and collections of stories from all over the world that deal with this idea of the impossible crime. But there’s a concentration within Japan. The Japanese traditional mystery is known as Honkaku, which is a term that means Orthodox Mystery. So, in other words, a mystery with a fair puzzle that plays by the rules. And these days, there’s been a kind of resurgence in Honkaku mysteries, known as Shin Honkaku, or the New Orthodox. The popularity in Japan is massive, and several of these books are being translated into English. As someone who loves puzzle mysteries, I’ve enjoyed delving into the past and reading the classic Golden Age authors. My favorites are Agatha Christie, John Dickson Carr, Ellery Queen, Frederic Brown, Helen McCloy, names like that, and people from the ‘30s to about the ‘50s. Also, alongside those authors, I’ve been reading classic Japanese and contemporary Japanese mysteries, which play by the same rule book where the focus is on a puzzle. It’s on identifying whodunnit, but also howdunnit. How could this impossible thing have occurred? As a writer, I think it’s all grist to the mill. I like to seek out these more diverse, perhaps unorthodox, or obscure, titles, and it’s a real joy to me as a reader and a writer.”

“You’re going to roll your eyes at this, but how in the world does one write a locked-room mystery? I don’t think I have the intelligence for it. Where do you start? Is it the ending, and you go backward? How does it work?”

“Now, that is a great question. To me, there’s no specific technique that I’ve hit upon. I’ve tried various approaches. But the idea is that you want every problem and every solution to be different. I should go about it differently each time. But I am a big fan of stage magic that I will come across in reading the book, hopefully, because my detective character—who’s very much a Golden Age pastiche of an amateur sleuth—is an old vaudevillian. I suppose he’s a retired conjurer from the London stage who has now turned his knack for unraveling impossible puzzles into the world of crime and detection. I grew up fascinated by stage magic, and I read a lot about magicians, how tricks are done, and the principles behind stage magic. So how, for instance, does a certain type of magic trick work on the brain, the part of the brain that is misdirected by a certain sleight of hand, and how does that sleight of hand work? I’ve read a few nonfiction works on that subject, and to be honest, the principles are very similar to mystery writing. I often liken writing mysteries to performing a magic show because, in both instances, you’ve got a performer guiding an audience's attention in a certain direction. In both instances, the trick's workings are in plain sight the whole time. But it’s about how you conceal them and ensure the audience doesn’t perceive them. In terms of plotting and writing, I suppose my general approach is the same as a magician’s. I will usually look at the effect that I want to achieve. It may be the case of coming up with an impossibility or a scenario that I think would be effective for the plot structure that I’ve got. Then, in some cases, it’s a question of working backward: how that trick can be pulled off via earthly practical means. This is an old stage illusionist’s principle of creating a gimmick that will achieve this effect. Then, at the other end of the scale, sometimes I will stumble across something, whether it be a trick or an illusion, an optical illusion, a misheard quotation, or a line of dialogue from something. It will stimulate something that I will then decide to try and develop into an impossibility. I’ve approached it from different angles, I suppose. Sometimes, I start with the trick itself, and I think about how I can incorporate that into my plot, and other times, I will have an unanswered question that I’ll need to devise my answer to.”

“Is there a specific type of sleuth that works well with locked room mysteries?”

“I suppose locked room mysteries are heightened by their nature. They’re non-naturalistic. They’re surreal. And there’s an emphasis on atmosphere. And I’ve already mentioned a sense of the eerie, the uncanny. I think the detective needs to be suitably larger than life, flamboyant, you might say, and theatrical, and these are the elements that I’ve distilled into my detective character, Joseph Spector. I think the amateur sleuth is a classic trope of the Golden Age. And a decidedly unrealistic, non-naturalistic one. I think the detective needs to reflect on the puzzle that you’ve set. With an elaborate and ornately contrived locked room mystery, you need a detective capable of these great flights of fancy and an air of performance about them. John Dickson Carr’s great detective was Gideon Fell, a boisterous kind of Falstaffian figure based on the author G.K. Chesterton. Then his other great detective was Sir Henry Merrivale, who was, if anything, even more flamboyant than Fell with a distinctive white suit and a penchant for practical jokes and the like. So, it is an almost cartoonish figure, but a figure that suited the puzzle framework that Carr created. A match made in heaven, I suppose.”

“Do certain types of plots lend themselves to locked room mysteries?”

“Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I generally talk about the Golden Age mystery. The Golden Age usually refers to the decades between the World Wars, such as the ‘20s and ‘30s, when writers like Agatha Christie rose to prominence, and I’ve also talked about Ellery Queen. So, novels featuring a closed circle of suspects are often set in high society. So again, it’s quite a lofty scenario, not necessarily one that would be relatable to the average reader. Often with a country house setting like the one in Cabaret Macabre. The most important components would be the cast of suspects, the so-called closed circle of suspects. In other words, a set cast of characters whose identities are known from the outset so that you know that the murderer is lurking somewhere among that cast of characters. The setting is typically isolated. In Cabaret Macabre, it’s the House March Banks, which is a highly conventional English country seat. But if you think of Agatha Christie, for instance, you have the Orient Express, you have that kind of idea of a cast of characters in that single location, or Death on the Nile, of course, you have them on that river cruise. I think those kinds of scenarios are particularly appealing for creating locked room mysteries. My second book, The Murder Wheel, was set mainly in the backstage corridors of a fictional London theatre. For a locked room mystery, it’s fun to have it set within the constraints of a specific location for an impossibility. I think these are the kinds of ingredients that I like to employ.”

“When you’re talking about your study of conjuring, you tend to be the type who likes to look behind the scenes. How do you explain the popularity of locked-room mysteries? Is it the puzzle? Is it like the people who love crossword puzzles or someone trying to figure that out? You’ve got that specific demographic.”

“I think it is. Exactly as you say. The appeal lies within the puzzle first and foremost, but the Golden Age has an irresistible charm. I started trying to write Golden Age style, pastiche whodunnits as an exercise in escapism at the height of the Covid lockdowns here in the U.K. in 2020 and into 2021. So that was when I wrote Death in the Conjurer in draft, again, purely to keep myself entertained and amused by playing with the tropes and the conventions of the Golden Age mystery. However, regarding the puzzle and the locked room, I think the great writers of locked room mysteries had a great insight into human nature and human psychology, allowing them to play with the readers’ perceptions and expectations. As a reader, I appreciate an author who doesn’t dumb down the plot and who doesn’t simplify the plot. I like a very labyrinthine plot, which encourages you to play along and sets you an intellectual challenge. These are the things that I enjoy as a reader. I think, generally speaking, when I’m talking to people who are reading my books, and when I’m generally talking about locked rooms, it’s that sense of the writer having fun with you, the reader, and addressing ‘you, the reader’ directly and engaging you in this kind of elaborate performance.”

“Okay, let me ask you this. And no modesty here, okay? Why do more writers not write these? I have my suspicion, and I think I disclosed it at the beginning of this interview.”

“Locked room mysteries are, by their nature, complex undertakings. It would be best if you had a passion for the genre as a reader as well as a writer because it would be easy to set out and try and create a locked room mystery by numbers, but it wouldn’t have the same impact as a locked room that was constructed by somebody who knows the genre in and out. I think I’ve been very fortunate in that I’ve had access to so many of the great titles from the past, and like I say, this influx of Japanese titles, translations of the French novels of Paul Halter—who’s another living legend of the locked room mystery. He’s a terrific writer and incredibly prolific. Speaking for myself, I’ve been able to read and distill all of that, generate my ideas from that, and combine it with the world of magic, which also fascinates me. But as to why more people don’t write the legitimate, locked room mystery style, I think other genres are perhaps less sophisticated in their construction and more commercially appealing—things like the conventional cozy mystery. Not to disparage the cozy mystery genre, but many titles are out there. There is a sheer glut of cozy mystery titles out there, and there are many recycled ideas out there. From a commercial perspective, selling a cozy mystery is easier because people know what to expect. They know how it will play out, whereas you are deliberately defying the genre's conventions with a mystery of the locked room. You are taking the established principles of the mystery, and you’re deliberately subverting them. And you’re making the work as unpredictable as possible because that’s the nature of it. I suppose that it’s more of a risk. It’s more of a balancing act because it can be a real disaster when it goes wrong. In a badly written locked room mystery, there’s much more to lose, whereas with cozy mysteries, there are many familiar elements for readers to latch onto. And there are so many long-running series out there that it’s perhaps easier to sell commercially. But again, not to disparage the cozy mystery because there are many cozy mysteries that incorporate locked room mystery elements. From a commercial point of view, I think the word cozy is a much easier sell than the locked room.”

“You’ve got to admit that writing and reading a locked room mystery take much more work because it’s not like you’re going to sit back in your leather chair and read this pleasurably. It’s like, okay, game on. Let’s go.”

“Exactly. I suppose it is perhaps more demanding, and therefore, the readers it will attract are those who love puzzles and trying to stay one step ahead of the detective or the author. The kinds of people who, like me, are fascinated by how tricks are done, who are, I suppose, as fascinated by that as they are by the tricks themselves. I mentioned a balancing act with locked room mysteries. It would be best if you had the reveal of the howdunnit to have a sense of satisfaction. You don’t want it to feel anti-climactic compared to the atmosphere and mystery you’ve constructed throughout the work. I suppose that’s what I mean when I say there’s more of a risk involved because you are essentially relying on this one gimmick to hold together the whole structure of the piece. You have to have faith that it will pay off, which is why I like to try different approaches within the same framework. I like to incorporate multiple puzzles, try to come up with puzzles that will complement each other and fit together rather like a kind of jigsaw, and try different types of illusions as well. You mentioned the boat illusion in Cabaret Macabre. There are conventional locked room mystery tricks, but then there are also identity tricks and things like that. There are tricks to do with alibis and what have you. I like to try to combine different types of things to maximize the satisfaction for the reader when all these tricks are unraveled. That’s the idea behind it.”

“As Spector would say, you’re building a house of cards.”

“Exactly.”

“For better or worse, it may turn out very well, or it may just completely collapse upon itself. You talked about the Golden Age quite a bit. Are locked-room mysteries era-dependent? Is it possible to write a locked-room mystery in today’s time with today’s forensic technology and law enforcement prowess?”

“Yeah, that’s a great question. I don’t think they’re dependent at all. There are many great examples of the locked room mystery throughout the latter half of the twentieth century, such as the post-Golden Age. But again, you must be more innovative and inventive to pull it off because information is so much easier today. With the Golden Age—which is what I love—you can rely on eyewitness accounts of events and things like that. These days, you’ve got CCTV. You’ve got an individual’s digital footprint to consider, and there are so many ways that the truth can be traced. In contrast, in the era that I write about, you were relying, I suppose, more on individual perception of an event or of an individual’s appearance—that kind of thing. To me, it’s closer to the principles of stage magic in that respect because when you’re in the audience at a magic show, you must rely on your own eyes and your perception of what’s happening around you. So that’s why I focus on that era. I’ve read many great works set far in the future, also some set in ancient Egypt or medieval times. Adam Roberts is an author who’s written some fascinating science fiction locked-room mysteries. They are fair playroom mysteries but set within this futuristic world he created. They’re quite a remarkable achievement, I would say. Likewise, I recently finished reading a Paul Doherty title. Paul Doherty writes historical mysteries, and he’s got a fantastic series set in the reign of King Richard II here in England. I think the principles are the same across the board, but I think if I’ve learned anything, it’s that the most fun and entertaining titles are the ones that are not afraid to break the rules or reinvent the rules of the genre.”

“As a wonderful writer of locked-room mysteries, what advice do you have for readers who wish to follow in your footsteps?”

“From my own experience, it was something that I did purely for my entertainment, and at the time I started writing, I was my audience, so I wasn’t writing for anybody else. If people want to write locked room mysteries, the same advice goes across the board. It’s to write the type of novel you enjoy reading, write the genre you like, write the period that most appeals to you, and create characters you enjoy reading and writing about. Those are the guiding principles that I’ve learned to live by. I think if people are looking to write murder mysteries, the best thing is to read a lot of murder mysteries, to focus on the type of mystery they love, to look at what makes it work, and to try and adapt those principles themselves.”

“Do what you love.”

“Precisely. It’s as simple as that.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference.

https://claystafford.com/

Tom Mead is a UK-based crime fiction author, including the Joseph Spector mystery series and numerous short stories. His debut novel, Death and the Conjuror, was selected as one of the top ten best mysteries of the year by Publishers Weekly. He lives in Derbyshire.

https://tommeadauthor.com/

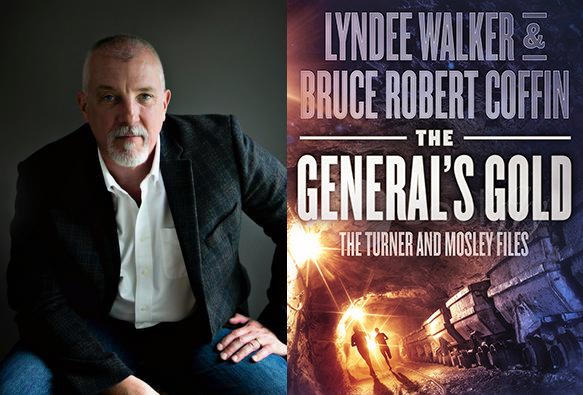

“Bruce Robert Coffin: Using Your Life to Write a Police Procedural”

Bruce Robert Coffin, retired detective turned bestselling author, shares how real police work shapes compelling fiction. From emotional authenticity to procedural accuracy, Coffin reveals what it really takes to write a great police procedural—and how any writer can get it right.

Bruce Robert Coffin interviewed by Clay Stafford

Bruce Robert Coffin has been coming to Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference every year since its early days, so it’s only fitting that we feature this incredibly talented writer as our cover story. To give a little backstory, Bruce wanted to be a writer, but after going to college and not necessarily receiving the encouragement or success he had hoped for, he chose a career in law enforcement. Little did he realize he was laying the foundation for the outstanding writing career that was to follow. I had a chance to speak with Bruce from his home in Maine. “Bruce, when you were a police officer, a detective, did you even think about writing again, or did you miss writing as you went through your regular job?”

“There’s nothing fun about writing in police work or detective work. Everything is bare bones. There’s not much room for adjectives or that type of stuff. It’s just the facts, ma’am. That’s what they expect out of you. So, everything is boilerplate. It’s very boring. You’re taking statements all the time. You’re writing. If there was one similar thing, and it certainly didn’t occur to me that there would ever be a time that I would write fiction again, but it did teach me to write cohesively. Everything that we did had to make sense. You know, you do one thing before you do the next. Building timelines for putting a case together, doing interviews with witnesses, and then figuring out how they all fit together, and making a cohesive story or narrative out of that to explain to a judge, a jury, or a prosecutor. As far as story building was concerned, I think that might have been something I was learning at that point because that’s exactly how a real case gets made. I wasn’t thinking about it in terms of writing later, but I think it’s something that helped me because I think my brain works that way now. I know how cases will work, I know how cases are solved, and I know why cases stall out. I think all those things really allow me to better describe what real police work is like in my fictional novels.”

“When you retired from detective work and started writing again, how much of the police work transferred over, and how much was fiction from your head?”

“I made a deal with myself when I started that I wouldn’t write anything based on a real case. I had had enough of true crime. I had seen what the real-life cases had done to people: the survivors, the victims, the families, and I didn’t want to do anything that would cause people pain by fictionalizing something that had been part of their lives. I made a deal with myself that I would write as realistically as possible, but I would never base any books on an actual case I had worked on. And I’ve so far, knock on wood, been able to stand by that. I think the only exception would be if it were something that had a reason. Maybe the family came to me and asked me to do that or something like that. There had to be a reason for it, though. And so, when I started writing, I could draw from a well of a million experiences, things that we tamp down deep inside, and you don’t think about how that affects who I am and how I see the world. And I think in my mind, I imagined I would be making up stuff, and that would be it. There’s nothing but my imagination. There would be nothing personal about what I was writing, and it would just be fun. And like everything you delve into that you don’t actually know, I had no idea I would be diving into the real stuff, like dipping the ladle into that emotional well and pulling out chunks of things from my past. There were scenes that I wrote that emotionally moved me as I was writing them. And it’s because what I’m writing is based on something that happened in real life. And I’m crafting it to fit into the narrative of the story I’m writing. But the goal of me doing that is really to evoke emotion from the reader, which I think is the most important thing any of us can do. You want the reader to feel something. You want them to be lost in your story. And I really didn’t think that was going to happen. But it’s amazing what I dredged up and continued to dredge up as I write these fictional police procedural stories.”

“Some of the writers I talk with view writing as therapy. Did you find it cathartic coming from your previous life?”

“I did. I think that was another shock. I didn’t think any catharsis was involved in what I was doing. But like I say, when you start delving back into things that you thought you had either forgotten about or thought were long past, it really allowed me to deal with things. It allowed me to deal with things I wasn’t happy about when I left the job. The things that I wish I could unsee or un-experience. As a writer, I was able to pull from those. I think you and I have talked about this in the past. I honestly think the best writing comes from adversity. Anything difficult that the writers have gone through in life translates well to the page. And I think that’s one of those things where, if you can insert those moments into your characters’ lives, your reader can’t help but identify with them. So, I just had the luxury of having the life we all have, the ups and downs, the highs and lows, the death and the love, and all those things we have to experience. But added to that, I had thirty years of a crazy front-row seat to the world as a law enforcement officer. So, using all of that, I think, has made my stories much more realistic and maybe more entertaining because it gives the reader a glimpse inside what that world is really like.”

“So, you have this front-row seat. And then we readers read that, and we want to write that. But we haven’t had that experience. Is it even possible for us to get to that point that we could write something like that?”

“It is. And I tell people that all the time. I say you have to channel your experiences differently, I think. Like I said, we all have experiences, things that are heart-wrenching, or things that are horrifying, or whatever it is in our lives. They just don’t happen with as great a frequency as they would happen for a police officer. And we all know what it’s like to be frustrated working for a business, being part of a dysfunctional family, or whatever it is. Everybody has something. And so, I tell people to use that. Use that in your stories and try to imagine. You know, you can learn the procedure. You might not have those real-world experiences, but you can learn the procedure, especially from reading other writers who do it well. But use your own experiences. Insert that in there. You know, one of the things that I think is the easiest for people to think about is how hard it is to try and hold down a job. Like, you go to work, and you may see the most horrific murder happen, and you’re dealing with the angst that the family or witness is suffering, and you’re carrying that with you. Then you come home and try to deal with a real-world where other people don’t see that stuff. Like your spouse is worried that the dishwasher is leaking water under the kitchen floor, and that’s the worst thing that’s happened all day, right? That the house is stressed out because of that. And it’s hard to come home. It’s almost like you have to lead a split personality. It’s hard to come home and show the empathy that your spouse needs for that particular tragedy when you’re carrying all those other tragedies from the day. And you won’t share those with them because you don’t want that darkness in your house. I tell people to try to envision what that would be like and then pull from their own life the adversity they’ve experienced or seen and use that to make the story and the characters real. You can steal the procedure from good books. Get to know your local law enforcement officer, somebody who’s actually squared away and will share that information with you. Don’t get it from television necessarily. Some of TV writing is laziness. Some of it’s because they have a very short time constraint to try and get the story told. So, they take huge liberties with reality. But if you can take that stuff and try to put yourself in the shoes of the detective and use your own experiences, you can bring a detective to life.”

“You think anybody can do it?”

“I do. I do think that you have to pull from the right parts of your life. And again, as I say, if you spend enough time with somebody who’s done the job and get them to tell you, it’s not just what we do. It’s how we feel. And the feeling, I think, is what’s missing from those stories many times. If you want to tell a real gritty police detective story, you have to have feeling in that. That’s the one thing we all pretend we don’t have. You know, we keep the stone face. We go to work, do our thing, and pretend to be the counselor or the person doing the interrogation. But at the end of the day, we’re still just human beings. And we’re absorbing all these things like everybody else does. So yeah, you have to see that. Get to hear that from somebody for real, and you’ll know what will make your detective tick.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. https://claystafford.com/

Bruce Robert Coffin is an award-winning novelist and short story writer. A retired detective sergeant, Bruce is the author of the Detective Byron Mysteries, co-author of the Turner and Mosley Files with LynDee Walker, and author of the forthcoming Detective Justice Mysteries. His short fiction has appeared in a dozen anthologies, including Best American Mystery Stories, 2016. http://www.brucerobertcoffin.com/

Submit Your Writing to KN Magazine

Want to have your writing included in Killer Nashville Magazine?

Fill out our submission form and upload your writing here: