KN Magazine: Interviews

Clay Stafford talks with Thomas Perry “On Crafting Unforgettable Characters”

Bestselling author Thomas Perry shares insights with Clay Stafford on writing emotionally layered, fiercely self-reliant characters—like Jane Whitefield—while avoiding info dumps, writing sharp dialogue, and building unforgettable protagonists that feel real from the first page.

Thomas Perry interviewed by Clay Stafford

I was curious to talk with bestselling author Thomas Perry to explore the inner architecture of his characters—smart, flawed, fiercely independent—and how writers can create protagonists like his who feel as real as the people we know. I got the opportunity to speak with him from Southern California. “Thomas, let’s talk about characters. All is a strong word, as my wife always tells my children, but all your protagonists are strongly self-reliant and emotionally layered. How do you write those so honestly without them appearing forced or contrived?”

“There are certain things for each character. For example, Jane Whitefield is a character that I’ve written in nine novels, and she was probably most in danger of being a superhero.”

“She knows an awful lot.”

“She does. Part of the fun is that she knows things that we know how she knows, how she learned them, who told her or showed her, or what experience caused it. When I first started writing, I wrote one, and then at Random House, my editor was Joe Fox, and he called me up—as editors sometimes do—and they say, ‘Working on anything?’ and you say, ‘No, I don’t like to eat anymore. It’s okay.’ No, I said, ‘You know, I’m working on this Jane Whitefield character again. I finished with that first story, but I’m not finished with that character. I feel like I know more about her, having written her, thought about it, and read a lot of background information, anthropological books, and so on. I’m doing it, and it’s going well so far.’ And he said, ‘Okay, well, talk to you later.’ And then about fifteen minutes later, he called and said, ‘How’d you like to make it five?’ And I said, ‘I don’t want to do a series.’ And then he mentioned a number and I said, ‘Sure, I’ll do it.’ High principle. After I’d written five of them, I wrote many other books that were standalone novels because I had been thinking of them over the five years I was writing those other books. At a certain point, I started getting letters from people and then emails. I finally got one that said, ‘You haven’t written a Jane Whitefield book in a couple of years. Are you dead, or have you retired?’”

“What did you reply?”

“No, the best reply is no reply. They think you’re dead.”

“How do you develop these character backstories and make your protagonists intriguing and deeply grounded without boring? How do you avoid that info dump we often want to put into our stories?”

“That’s where you must learn to cross out. Do I need this? Is this information that everybody must have to understand, or to move the story along? Get rid of it. It’s great to write it. You understand it, and it helps you with everything else about that character you’re writing, but you don’t have to lay it all out on the table and make everybody read it. As Elmore Leonard said famously, ‘Cross out the things that people are gonna skip over.’ I think that’s probably still true.”

“I love the way that you introduce characters. On the first pages of any book, your characters come fully formed. They’re not developing. How do you introduce them like that? Is there a trick that instantly signals they’re competent and deep, without over-explaining? It seems like we turned our private camera into their living room, and they are real people right there from the start.”

“I’m glad they seem that way. I don’t know. I like to start by acquiring the reader’s attention, trying to get the reader to pay attention to what I’m doing. There are a lot of ways of doing that. One of them is to slowly build up over a couple of pages to see what’s about to happen, and then you see them in action. That’s ideal. But the craziest beginning I think I ever wrote was—I can’t remember which book it was; it’s probably Pursuit, so you may remember—very first thing, ‘He looked down on the thirteenth body.’ He’s a cop. He’s the expert, and he’s going through this crime scene. At that point, you realize that the action has started, and you must sort of scramble to catch up and find out what’s happening as he finds out. He doesn’t know yet, either. He knows he has his skills and this experience, but we don’t. We’ll try to hitchhike with him to find out what this is.”

“Your characters—whether it’s Jane Whitefield, or in recent Pro Bono—have a kind of intelligence and resourcefulness, where I wish I were that intelligent and resourceful. Your books are full of moments where characters outthink or outmaneuver dangerous situations and have the believable skills to do that. How do you show that without creating a caricature of sorts?”

“It’s fine-tuning. It has to do with whether I have gone too far. Is this sublime or ridiculous? You must be your worst critic because harsher ones will be along shortly.”

“Does that tie into the character’s philosophy or code of ethics? You put it in there, but you don’t preach it. You know enough to make it work.”

“It’s all about characters. Who is this person? One of the ways we find out who this person is, is what the furniture of their mind is. What’s their feeling about life and human beings? You must know who he is to have a character you want to follow through a book. Not all at once, ever. It’s always as you go, you come to know them better. You see them in action, the things that they worry about or think about, how they treat others, and so on.”

“You reference the furniture of life. Your protagonists rarely wait for someone else to move the couch. They do not want to wait for someone else to solve their problems. How do you ensure that growth and change come from within the characters rather than external forces?”

“I sometimes feel it’s necessary to have a situation where, for one reason or another—sometimes complicated and sometimes simple—if this character doesn’t step up, nobody will. He’s the only one with experience and knowledge about something or another, or he’s a person who does things that don’t involve the law. Like Jane Whitefield, everything she does is illegal. Everything. Since I started writing about her, it became more illegal, and they hired hundreds of thousands of people to make sure it doesn’t happen. Jane must change and trim back what she does, which is an interesting thing to play with, and introduce a character who is on the run and figure out how that person will survive if someone’s after them wanting to kill him.”

“You’re talking about Jane, and she’s one of my favorites regarding dialogue. You write dialogue very well. How do you use dialogue to reflect the characters’ self-reliance and hint at their backstory without making it that info dump?”

“Small doses. They’re the doses relevant at that moment. It’s something she knows, and we know how she knows, which is a helper. That makes it less crazy. Also, she must invent things on the spot. It’s like providing evidence. You’re trying to present a character you know can do these things and that others will accept can do these things.”

“Your protagonists aren’t superheroes. They make mistakes, they carry burdens, and they have flaws. How do you include those flaws that enhance rather than undermine a character’s strength and credibility? Because the flaws certainly add reality to things, yet you don’t want to do something disparaging to the character.”

“The flaws in Jane Whitefield, for instance, have often to do with the difficulty of what she does and still being somebody’s wife in Amherst, New York. You can’t be going off and having these fantastic adventures and expect your husband to wait for you and say that’s fine. There’s the constant where she’s trying to handle that, trying not to lie to him, but she can’t tell him many things that are going on, because if you tell somebody something, there’s a chance they’ll let it slip. If you don’t tell somebody something, there’s no chance. She has left home several times and is returning a few weeks later.”

“In your extensive experience, what separates a character that readers admire from one they never forget, like Jane?”

“Dumb luck. You know, we try. We do our best. Sometimes it works.”

“Dumb luck? Do you really think so?”

“I think you learn more as you go along. It’s a tough thing to do. Part of it is sincerity. I admire her. Therefore, there are probably subtle clues in there somehow that she’s someone to admire, because I don’t say anything bad about her—just stuff that’s a problem because of what she does. It’s odd to be doing, but it has a background in the Northeastern Indians’ history. It was a situation where people were brought into the group and adopted, particularly by the Haudenosaunee. The Iroquois were big adopters, partly because they were fighting a lot. They lost a lot of people. In the 1630s, a Dutch explorer came into western New York and noticed in an Oneida village that people from thirty-two other groups lived there. It’s a lot of people.”

“In some part of our schizophrenic brain, do you view a strong, memorable character like Jane as real?”

“Real to me. Yeah. I miss her when I haven’t written about her for a while. I miss that attitude, that self-reliance, and at the same time, that great concern for other group members.”

“She would be pleased to hear you say that. Is there any advice we haven’t discussed on building characters that would help writers build their own memorable and self-reliant characters?”

“If you’ve ever read it before, don’t do it. That includes things like occasionally, there’ll be an homage to somebody or other, and I think it’s a waste of time because the other person did it better—the one who wrote it first.”

“In all things, be original.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference, The Balanced Writer, and Killer Nashville Magazine. Subscribe to his newsletter at https://claystafford.com/.

Thomas Perry is the bestselling author of over twenty novels, including Pro Bono, Hero, Murder Book, the critically acclaimed Jane Whitefield series, The Old Man, and The Butcher’s Boy, which won the Edgar Award. He lives in Southern California.

Clay Stafford talks with Andrews & Wilson “On Collaborating”

Bestselling thriller authors Brian Andrews and Jeffrey Wilson—known collectively as Andrews & Wilson—discuss their journey from solo careers to a powerhouse writing team. In this candid conversation, they reveal their creative process, how they manage co-authoring, and advice for writers considering collaboration.

Brian Andrews and Jeffrey Wilson interviewed by Clay Stafford

I was excited to sit down and talk with Brian Andrews and Jeffrey Wilson, the acclaimed co-authors of the #1 international bestselling author team of Andrews & Wilson, who are unparalleled in action thrillers. I wasn’t disappointed. Their mastery of the genre, evident in their numerous bestsellers, makes them the perfect tour guides for those of us who aspire to craft compelling action scenes, but also their collaboration style is something to be envied. Moreover, their approachability and wealth of knowledge make them a team you can comfortably learn from without feeling intimidated.

Clay: “Brian and Jeffrey, you’re a writing team, but before you became that, can you tell us a little about your solo careers before your very successful collaboration?”

Brian: “I have a psychology degree from Vanderbilt.”

Clay: “Very helpful for a writer.”

Brian: “Very. I was always interested in the mind and how people think. I think that helps inform my interest in character and human dynamics. Then, I made a hard pivot when I went into the military, became a nuclear engineer, and was a submarine officer. That informed me of my interest in mechanical things and engineering and how things work. Living on a submarine is obviously like the ultimate Skinner Box. It's a human experiment. You shove a hundred people into this machine that has a nuclear reactor and can carry nuclear weapons, and you put it underwater where you're driving around, and you can't see where you're going; everybody's trapped inside, breathing recycled air, and eating three-month-old food. That's the perfect platform for me to think about microcosms. And every story is a microcosm. I lived in the microcosm of a submarine.”

Clay: “And that makes me think you're living the dream, the way you described that one.”

Brian: “Living the dream. Now they let me out, which is great. And make sure you put in the interview somewhere that there's a great irony that a submarine officer who was reading Hunt for Red October on a submarine chasing Russians around has an opportunity, twenty-plus years later, to write on the 40th anniversary of Hunt for Red October, a submarine novel about a submarine chasing Russians around. So that's a cool full-circle element. When you're out there serving, you're away from your family, you're away from your friends, you're bonding with the other servicemen and women in your community. One way you bond is to share stories, tell stories, and talk about what matters to you and what you're afraid of. It's how we digest and connect with people through storytelling and listening to stories. I think that military service helped weave this into my DNA. That storytelling is an important part of our community, and getting stories out there about the men and women they're serving, what they're going through, and what it feels like is important for the rest of the nation. The people who are not serving and maybe aren't familiar with military service or the sacrifices men and women make to keep the nation safe. What inspired me to want to be a storyteller is how story time was part of the community I lived in.”

Clay: “How about you, Jeff? Your solo career before you got into this partnership?”

Jeffrey: “Mine is the complete one-eighty-degree opposite of Brian's. Brian came into storytelling after all his experiences. And I had all these experiences because I'm still that nine-year-old with a rifle or the fire hat or whatever. My bio reads like someone who never grew up, which might be partly true.”

Clay: “We'll ask your wife.”

Jeffrey: “Right. No, I know better than that. Writing is the one great constant in my life. When I've done all these other things, being a pilot, being in the teams, being a doctor, and a firefighter, and all the things I've done, I always wrote. I started writing when I was probably my daughter's age, which is eight. I would write fan fiction for my favorite shows and published my first short story when I was 13 or 14. I've literally always had storytelling as part of my life. At times in my life, it was my catharsis; at times in my life, it was my creative outlet, and at times in my life, it was a passion that I wanted to turn into a career, which I've been blessed to do now. It's kind of the opposite of Brian. The writing was always there, and then I lived all these other lives that slowly informed that craft and helped me develop it differently. When Brian and I met, I believe he had two novels out. I had two out and a third about to come out. We were both writing individually, and this partnership grew out of friendship rather than necessity. We were writing, and we connected at ThrillerFest in New York. Because of my social paralysis, I'm uncomfortable in big groups of people, and my wife laughs about it because I do well. I think I look okay socially, but I don't like it. I was sitting in the hotel room looking through all the pictures of the people I might meet at this opening meeting during our debut author year when Brian and I were both debut authors. I was finding all the military people. I was like, ‘Okay, I can talk to those guys. We'll have something in common.’ Brian happened to be one of them, and I was burning the pictures into my head so I would recognize them at the cocktail party. And sure enough, I saw Brian there and said, ‘Hi.’ He was alone because he was a submariner, so he was crying in his beer, and I felt sorry for him. The partnership part of it came much, much later. But the history was there for both of us. I think that made it work.”

Clay: “How did the collaboration start?”

Jeffrey: “He stalked me like a little girl. It was weird.”

Brian: “Now remember he just explained how he stalked me.”

Jeffrey: “I think I said I felt sorry for you.”

Brian: “I think you stalked me. I believe what you just described is the definition of stalking. No, I think he charmed me.”

Clay: “This sounds like me telling how my wife and I met and got together, and mine is all lies.”

Jeffrey: “It's very uncomfortable, isn't it?

Clay: “But between all the stalking and the give-and-take and the ‘I don't want to see you anymore,’ how did it eventually work out?”

Brian: “All kidding aside, we met at ThrillerFest at the cocktail party and became fast friends. Our family values are similar. We have the same sort of world outlook, and we're both driven and intellectually curious people. We joke about Jeff’s bio all the time. Also, I have a variety of experiences, and we're both intellectually curious people who are interested in this world that we live in and in storytelling. If you put all those things together, it does make sense that we would become friends. Every year, we look forward to catching up at ThrillerFest, and I think during our third year there, I was thinking about my next project, and the idea just popped into my head. I said, ‘You know, we should do a SEALS and Subs book because combining those two communities in the story would be cool.’ And he's like, ‘That does sound interesting. I don't know how that would work, you know. I don't understand. You know, writing is a very individual thing. How could we possibly make this work?’ and I didn't have a perfect answer. I said, ‘Well, we could just try dividing the chapters and see what would happen.’ I think Jeff was like, you know, in his mind, he's thinking, ‘I don't see this happening.’ So, he was like, ‘I'll help. It sounds like a cool idea. I'll be your subject matter expert. I'll help you with whatever you need from naval special warfare, that sort of thing.’ The same advice he was giving earlier. He said, ‘I'll offer to be that resource for you. And I said, ‘Okay,’ and then I said, ‘Well, why don't you look at this chapter? And maybe you could help write it.’ Then he started getting into it because he's a storyteller and couldn't help himself.”

Jeffrey: “He manipulated me with his psychology degree. The story's true ending is that I did go into it thinking I have no idea how I've been writing my whole life. I don't know how two people write together. You do the nouns; I do the verbs? What are you even talking about? And I did want to help him because he was a good friend. The story became increasingly developed because we were brainstorming, which turned into a really good story. He asked me two more times after the first time, ‘Why don't we take a crack at writing it together?’ I said, ‘No, no. Again, I don't know how we would do it.’ This was a great book, and I was jealous. He said, ‘Look, let's do this. Let's write five chapters. We'll divide them up. You write some. I'll write some. We'll talk about it. We'll try it out, and if it's working, we'll keep going. If it's not working, you can have the story because I don't think I can write it without you.’ And I was like, ‘Sweet. I gotta have this story to be my story.’ And so, we sat down, started writing the chapters, and as I recall, we just kept going. We never even brought it up again. It worked so well that it didn't even occur to us to have the conversation again. I think Tier One, the first book we wrote together, was done in four and a half months. We crushed it. Outside of interviews, we've never talked about it again. It's a given that this is how we do it. It's efficient. It's so much more fun. I'm sure if your writing partnership isn't what ours is, it would be horrible if you weren't getting along. We never argue about anything. It's enjoyable. I get to do the job I love with my best friend. There's no downside to it, and we're incredibly efficient. As you know, we release three or four books a year. So, we turn a book in about every fourteen or fifteen weeks. We couldn't do it alone. But it's just so enjoyable. And there's no writer's block. You get on the phone like, ‘I'm not sure what to do.’ You get on the phone, and five minutes later, the idea is better than anything you would have come up with individually. It's been a real joy. At first, I didn't see how it could work, and now I can't even imagine doing it any other way.”

Clay: “You guys live in different cities, too.”

Jeffrey: “Thank God, because we are good friends. We’d get nothing done.”

Brian: “We'd watch Jim Gaffigan and drink Bourbon every day, and we'd have no books.”

Clay: “So that's a good thing. How do you plan your stories? Because you've got two brains here trying to work independently but together. How do you plan the stories out?”

Brian: “Do we have two brains, Jeff?”

Jeffrey: “I think we used to. He's making a joke, Clay, because, for the last couple of years, we've realized that we've hybridized into a single organism to the extent where I'll have a brilliant idea like, ‘Oh, my gosh! I know how to solve that problem we were talking about this morning,’ and I'll get on the phone with him. I'll say, ‘Hey, I want to tell you something,’ and he’ll go, ‘Hold on!’ and he'll tell me exactly what I'm about to say. It's bizarre.”

Clay: “Twin telepathy, right?”

Brian: “Yes.”

Jeffrey: “It’s weird, man. It's a real thing. But anyway, Brian, what were you going to say?”

There’s a pause.

Clay: “Jeff, with twin telepathy, you should know.” I laugh.

Brian: “That’s what I was going to say.” I laugh again. “It's a funny joke, but I feel like there is some of that now that we've written so many books together, where it's like two dozen novels we've penned together that we start to anticipate. And you know, we have a method, but I think, as far as an individual, we're not plotters, and we don't outline the entire novel as some people do. We're in the pantser category. But we do have structure to our approach. We write in the three-act structure. Our books are written from multiple points of view in third person. So, we sort of approach this as, like any good group project, which is at the beginning of every novel, we sit down and talk about the story's themes and objectives. In broad strokes, where do we think we want to end up? And then we start division of labor. Because we write multiple point-of-view novels, we can each take different characters and write a single point-of-view per chapter. We divide the chapters between us, and it's just the first couple because we're not sure exactly where we will go. So maybe Jeff will take chapters one, three, four, six. I'll take two, five, and eight, and we start writing and write in parallel. We write simultaneously, and the key to our success, and I would say, our superpower, is that throughout this process, we're always talking and giving each other free reign to edit each other's work. Would you agree with that?”

Jeffrey: “I think that is the key—every few chapters, we swap. If I finish a chapter, I send it to Brian. When he finishes his, he sends it to me. So, it doesn't go into “The Manuscript,” our master file, until I've written it and he's edited it, and vice versa. So even though we're writing in tandem and writing different chapters, both of us have touched every chapter before it goes into the master file, which is a little weird but is our superpower because it gives us that unified voice. Sometimes, you can tell when something's co-authored because you can say, ‘Okay, that clearly is a different voice.’ We don't have that problem. But the other thing is, we're editing as we're going. We're also stimulating each other as we're going. I'll send him a chapter. He'll send me one. I'll read his and be like, ‘Oh, my God! I know what we can do with this!’ Now I'm off to the races writing something else because we have that sort of logarithmic increase in creativity. After all, we're both seeing it. So yeah, I do think that's the superpower. We did that from the very first book. We've never not done it that way. I don't think it would work any other way.”

Brian: “Clay, you said something early on that guided our partnership. Jeff was like, look, we need to approach this as a business. This is a business, and the book is our product. It's not about who wrote what chapter or who thought of what idea on what page. In an interview, you’ll never see us saying, ‘Well, I wrote this, and then Jeff wrote that.’ That's not how it works. This book is like a kid to us, you know. It's like anybody who's a parent understands that you can't take credit. These books are like our kids, and we both try to put the best guidance and put our all into making the book as exciting, informative, and suspenseful as possible. And it's between the two of us and our little additions all through this process to the point where you can't name who did what, on what day, and what page. It's just an Andrews & Wilson book, and once it's out there, that's the thing we're proud of. We're not proud of, ‘Oh, well, I thought of this great thing on page thirty-seven.’ That's not how we work.”

Jeffrey: “Literally, it's not how we work like there are times when my wife will read a book, and she'll be like, ‘Oh, chapter 17, that was you,” and she thinks I'm making it up when I swear I don't know if I wrote that first or second. I remember that chapter. I had something to do with it, but by the time it gets into a book you're reading, one of us wrote it, the other rewrote it, then it all got edited, then it went to DE, then it got edited again. That lack of ego is the key, and that's from the military background because it's part of your DNA. If you spend significant time in the service, the team and the mission are before you. It's more than a bumper sticker. It becomes who you are. It's all about the team. It's all about the mission. It's not about credit. It's not about who did what. You can't drive an eight-billion-dollar submarine by yourself, and one dude doesn't fast rope in and get Bin Laden, right? It's all team before self with our backgrounds. That's what made it so easy, and it is, I guess, the best way to say it. It made it easy because it's who we are.”

Clay Stafford: “Did you guys draw up a contract? If somebody's going to start collaborating with somebody else, how involved should the legalities get?”

Jeffrey: There should be something. I think how detailed it needs to be depends on your business relationship. Don't ever sacrifice a personal relationship. How many friendships have been ruined over a business deal, right? There should be a discussion about what you want to do, even outside the contract. That was the key to our success. From day one, we talked about what we were trying to achieve. What was our goal? We were on the same page, not just on the creative side but the business side. I don't think I’ve thought about it in years until you just brought it up. I'm sure it's invalid now, but we had a document when we started, but it was super simple. Whatever comes out of anything we ever write as Andrews & Wilson is fifty percent yours and fifty percent mine. Every bit of responsibility, every bit of liability, every bit of financial success, is split down the middle fifty-fifty. Ours was a one-page document we wrote and then gave to our agent. I think there should be something. It would be a mistake not to have something to point to if there were ever conflicts. But even more important than the legal document is that conversation of: what do you want to get out of this? What do I want to get out of this? Are we on the same page? Are we on the same page creatively? Are we on the same page business-wise? That's very, very important.”

Brian: “The exercise of addressing these questions and drafting something forces you to have a conversation that might be uncomfortable or feel awkward otherwise, and you might just sort of kick that can down the road. You may not be on the same road if you kick it down too far. I think that, more than anything, the business discussion is super important. As we discussed, we try to give back to the community because the community has given so much to us. One of the things that I always ask aspiring authors when they ask for help is, ‘Well, what do you want to get out of your writing career? Do you want to have a book out there that everybody can read? Is it that simple? Is it that you want to say I'm a New York Times bestselling author? Do you want to be rich and famous? Do you want to have your book adapted into a movie?’ It can be all those things, or it can be one of those things. But if your writing partner has different aspirations than you, then that's important to establish upfront because you will be rowing in this same boat and must be rowing in the same direction at the same pace. It’s difficult to make a living in this business. It's competitive. And for most people—and there's no shame in saying this—writing is a side gig, and it takes a long time until you make enough money to call it a career and write full-time. And if you're two, you're splitting all that money. It might be a situation where one person's financial needs differ from the others, and they say, ‘You know what, we’re not making enough money for me to continue this. I have to work on the side. I have to have my day job.’ Okay, is it a situation where one person works eight hours a day and the other works two? Are you guys okay with that? How does that look? These logistical questions are important, so everybody's expectations are on the same page at the beginning of the partnership.”

Clay: “We talked about all the good things and the symbiotic relationship you guys have. What are the challenges of team writing?”

Brian: “The challenge is we're producing so much content right now. How do we keep it fresh? How do we stay motivated? How do we ensure the other guy gets time with his family? We spend a lot of time ensuring that our family needs are met, our financial needs are both met, and we're still having fun. And so, there are conversations about, ‘I'm going to be going on vacation now,’ or ‘This book is gonna be due then,’ and ‘Okay, I got a family thing.’ And so we do a lot of planning and communication constantly to make sure the other guy’s emotionally, professionally, and financially okay. And that's been something that we've done from the very beginning. As Jeff said, we're best friends and business partners, so we must ensure that both elements are taken care of.”

Clay: “It’s that team spirit you discussed earlier.”

Jeffrey: “Yeah, one hundred percent. We've been writing together creeping up on a decade in a couple of years, and I'm not saying we always agree. But we've never argued. I don't think there's ever been a conflict. We're both faith, family, country. Those are all more important than what we're doing as long as our financial needs are met. And so, Brian calls and says, ‘Hey, I'm not going to be able to do this thing that we just got asked to do because Larkin's got something going on,’ no problem. I'll take care of it, and vice versa. We've always been team before self. On the creative side, it's the same thing again. It's not that we're always one hundred percent on the same page, but we have that team dynamic. Let's say there's something, and Brian calls up and says, ‘Well, you know, I don't know about this. I think maybe we go in this other direction.’ That has only happened a few times, but our sort of unspoken rule—it's been spoken about in interviews, but I don't think we ever planned it out—has always been we talk about the pros and cons of your idea versus my idea, and we tend to defer to whoever has the most passion for it. I might think his ideas aren't as good as mine, but he feels very strongly about it. Let's try it because it's writing; you can always change it, right? When we've trusted the other guy's passion, it's never been like, ‘I told you, I knew that wasn't going to work.’ It's always worked. And so there hasn't been any real conflict because we're proactive and team before self in our approach.”

Clay: “And all that would sound great to somebody reading this. Any advice for those thinking about collaborating with another author?”

Jeffrey: “I mean just the advice we've given, I think, which is, vet the relationship, and I don't mean vet it in a cold, clinical way. I mean, make sure that it will work not just for you but for the other person, and have those big upfront conversations. If you have a real conversation about expectations, goals, craft, business, all those things, you'll know if it will work. There’s not a huge number of collaborators, but the people who have conflict have conflict because of unspoken expectations and unmet needs. And so, if you can be upfront about those things and decide at the beginning that you're on the same page, you shouldn't have insurmountable conflict. Maybe I'm naive, but it seems like it would be true.”

Brian: “And I think you have to be honest with yourself about the needs of your ego. Why are you doing this? Is it because you want to say you wrote this book? For us, it's about the books and the brand. And so, if you think about it like a rock band, a lot of rock bands, just the lead singer is considered the band, and everybody else is sort of baggage along for the ride. For other bands, it's not that way. Everybody's sharing equally in this. So, in your partnership, is it about you, or is it about the team? Liv Constantine and her sister do a great job with this. It's about the two of them. But they're sisters, right? They're another enduring co-author team; if you talk to them, you can tell it's not about their egos. It's about them together.”

Jeffrey: And I will say, though, as a caveat to that, that doesn't mean that's the only model that works. It's what works for us. Catherine Coulter wrote with J.T. Ellison for a time. That relationship wasn't our relationship. Kathy was ginormous, and J.T. was breaking out. Theirs was more a mentor/mentee co-authoring relationship, which worked great. The books were good. Those relationships are all different. We're not saying it must be team admission before self, 50/50, or it can't work. We're saying, make sure you know what it is and what it looks like. There's nothing wrong with saying, ‘My goal is to write with somebody who has a following and get my name out there and have that association,’ as long as you both understand that's what you're doing and are both okay with it. That can still be a great model, but not talking about it and making sure you're on the same page is the death of the relationship.”

Clay: “So there’s many ways to structure it. Excellent advice for those thinking about a collaborative relationship.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. https://claystafford.com/

Brian Andrews is a US Navy veteran, Park Leadership Fellow, and former submarine officer with a psychology degree from Vanderbilt and a business master's from Cornell University. Brian is also a principal contributor at Career Authors, a site dedicated to advancing the careers of aspiring and published writers. https://www.andrews-wilson.com/

Jeffrey Wilson has worked as an actor, firefighter, paramedic, jet pilot, diving instructor, and vascular and trauma surgeon. He served in the US Navy for fourteen years and made multiple deployments as a combat surgeon with an East Coast-based SEAL Team. He lives in Southwest Florida. https://www.andrews-wilson.com/

Paying it Forward

Author, editor, and publisher Judy Penz Sheluk talks with Charlie Kelso about fiction, short stories, anthologies, and her path from journalist to indie press founder. With insights on writing, editing, submitting, and publishing, Judy shares her experiences behind Larceny & Last Chances and her broader mission to pay it forward through storytelling.

An Interview with Writer, Editor and Publisher Judy Penz Sheluk By Charlie Kondek

If the name Judy Penz Sheluk keeps popping up in your reading, that shouldn’t be a surprise. She’s published two series of mystery novels, the Glass Dolphin and the Marketville books, in addition to numerous short stories and articles. Her books on publishing—Finding Your Path to Publication: A Step-by-Step Guide and Self-publishing: The Ins & Outs of Going Indie— are valuable resources for the emerging or experienced writer navigating the ups and downs, about which Penz Sheluk knows a great deal. Based on those experiences, she runs her own label, Superior Shores Press, which has released its fourth anthology of crime and mystery stories, Larceny & Last Chances. The anthology features 22 stories from some of today’s most engaging writers (including me, the author of this interview, who is bursting with gratitude at being in their company).

Penz Sheluk is a member of Sisters in Crime International, Sisters in Crime – Guppies, Sisters in Crime – Toronto, International Thriller Writers, Inc., the Short Mystery Fiction Society, and Crime Writers of Canada, where she served on the Board of Directors, most recently as Chair (whew!). While putting the finishing touches on Larceny & Last Chances and working to promote it, she took some time to let me pepper her with questions about the new book and her wide range of experiences across her various roles. As always, the advice she can give a writer was ample, as is the excitement over the work. Here’s what she had to say.

CK: You had a long career in journalism before you started publishing fiction. What got you started on fiction? What keeps you writing it?

JPS: I’ve been writing stories “in my head” since I started walking to and from school as a young kid. Sometimes those stories would be short and take up one leg of the journey (about 20 minutes). Other times I’d keep them going for a few days. I honestly thought everyone did that until I mentioned it to my husband one day after a frustrating traffic-jammed commute. Something like, “Thank heavens I had that story going in my head.” I can still remember the stunned look on his face when he said, “You write stories in your head?” To his credit, he registered me in a 10-week creative writing course as a birthday present. My first publication (in THEMA Literary Journal) was a result of that course. I’ve never looked back.

CK: You’re a novelist as well as a story writer. Which came first? What’s it like for you, working in both formats?

JPS: I started with short fiction, but if I have a preference, it’s writing novels. I’m a complete pantser and, while that works well when you have 70,000 words to play with, it becomes problematic when you’re trying to tell a tale in 5,000 words or less. ‘The Last Chance Coalition,’ my story in Larceny & Last Chances (2,500 words) took me about two weeks to write! That’s the equivalent of two or three chapters, and when I’m working on a novel, my goal is a chapter a day. I have tremendous respect for short story writers.

CK: Then there are the anthologies. I don’t need to tell you how excited I am about Larceny & Last Chances. All the stories are so good. What got you into assembling anthologies, and how do you generate the theme for each?

JPS: I got my start in short stories. I mentioned THEMA earlier, a theme-based literary journal, and that inspired the theme-based anthology idea. But it wasn’t until I had two published mystery stories in 2014 that I really thought, “Hey, I can do this.” When I decided to start Superior Shores Press in 2018 (following the closure of both small presses I’d been published with), I knew I had to give the press some legitimacy. It seemed like a win-win. Pay forward my own success, and establish SSP as the real deal.

As for themes, the first was called The Best Laid Plans (because it really was a risk and I had no idea what I was doing). After that I got into alliteration! Heartbreaks & Half-truths, Moonlight & Misadventure, and now, Larceny & Last Chances. I try not to make the theme too restrictive—e.g. no mention of murder—so that writers can explore their inner muse.

CK: What are the top two things you look for in an anthology submission?

JPS: 1) It must meet the theme, but not in an obvious way. Surprise me and you’ll surprise the reader. 2) A great ending. When I’m reading a story, sometimes I’ll be on the fence, and then the end will just blow me away. And so, I’ll reread the story, thinking, “How can I make this better, so I’m not on the fence?” And if the ideas pop at me, rapid fire, I know it’s a yes. Usually it’s stuff like too much backstory, or too many characters. Both are easily corrected if the author is amenable. In my experience, most authors only want to improve their work, and so they are largely receptive to any suggested edits.

CK: What are reasons you might reject a submission?

JPS: 1) Sloppy writing, and by that I mean not just missing commas or spelling/grammatical errors, but a lack of attention to detail. 2) For Larceny, I received a few submissions that had clearly been rejected for a recent location-themed anthology. I understand that good stories get rejected for any number of reasons, but as an author, you should make the effort to improve (and change the locale, if need be) before submitting to the next market. 3) The premise is unimaginative. I want you to be on theme, but it can’t be obvious and the ending should surprise or satisfy (and hopefully, both). 4) Werewolves. I really do not get werewolves.

CK: I’m sure a lot of people ask you about publishing, based on your experiences, your articles, and your books on the topic. What are the most important pieces of advice you find yourself giving people?

JPS: Publishing is a business like any other. Rejection isn’t personal. And while there are exceptions, it’s the big names that will get the big bucks. I remember a writing instructor telling me: “If you want a six-figure publishing deal, become a celebrity. If you want to learn to write well, start with this class.”

CK: Thanks so much for taking the time for this, Judy!

JPS: My pleasure, Charlie. I’ve registered for Killer Nashville (my first time!) and can’t wait to meet Clay Stafford and the many writers and readers who will be attending this year’s conference.

Larceny & Last Chances: 22 Stories of Mystery & Suspense

Edited by Judy Penz Sheluk

Publication Date: June 18, 2024

Sometimes it’s about doing the right thing. Sometimes it’s about getting even. Sometimes it’s about taking what you think you deserve. And sometimes, it’s your last, best, hope. Edited by Judy Penz Sheluk and featuring stories by Christina Boufis, John Bukowski, Brenda Chapman, Susan Daly, Wil A. Emerson, Tracy Falenwolfe, Kate Fellowes, Molly Wills Fraser, Gina X. Grant, Karen Grose, Wendy Harrison, Julie Hastrup, Larry M. Keeton, Charlie Kondek, Edward Lodi, Bethany Maines, Gregory Meece, Cate Moyle, Judy Penz Sheluk, KM Rockwood, Kevin R. Tipple, and Robert Weibezahl.

Buy Link: www.books2read.com/larceny

“Robert Mangeot: Short Stories and the Big Honking Moment”

Mystery writer Robert Mangeot discusses the art and craft of writing short stories, including structure, compression, voice, and the elusive “big honking moment.” With credits in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, MWA anthologies, and more, Mangeot explains what makes a short story resonate—and how writers can develop their own sense of story unity and emotional payoff.

Robert Mangeot interviewed by Clay Stafford

Since the inception of Killer Nashville, the name of Robert Mangeot has been a constant presence, a beacon of inspiration for aspiring short story authors. His literary prowess has been recognized in various anthologies and journals, including the prestigious Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, Black Cat Mystery Magazine, The Forge Literary Magazine, Lowestoft Chronicle, Mystery Magazine, The Oddville Press, and in the print anthologies Die Laughing, Mystery Writers of America Presents Ice Cold: Tales of Intrigue from the Cold War, Not So Fast, and the Anthony-winning Murder Under the Oaks. His work has been honored with the Claymore Award, and he is a three-time finalist for the Derringer Awards. He’s also emerged victorious in contests sponsored by the Chattanooga Writers’ Guild, On the Premises, and Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers. His pedigree in the realm of short stories is truly unparalleled.

“So, Bob, how are short stories different from novels other than the length?”

“They are entirely different organisms. Novels, done right, are interesting explorations of something: theme, a place, a premise. The novel will view things from multiple angles. Short stories may, too, but novels will explore connected subplots. They might have many points of view on the same crime or the same big event, or whatever the core thing of the story is so that you get an intense picture of the idea of what this author is trying to convey, even if it's just to have a good time. Novels are an exploration. And they will take their time. I'm not saying they're low on conflict, but they will take their time to develop the clues, develop characters, and introduce subplots. Potentially, none of that is in a short story, right? The short story is not a single-cell organism but a much smaller one in that everything is all part of the same idea.”

“How do you get it all in but make it shorter?”

“There aren't subplots. There are as few characters as you can get away with. Once you get those baseline things down, it’s about compression. No signs, no subplots. Just keep on that straight line between the beginning and ending. Once you've mastered that, there's a bazillion ways to go about it, but you must meet those baselines. Everything connects to the whole, and—I know I overuse this—but the construct that I always go back to is Edgar Allen Poe. He called it unity of effect. He often talked about emotion, so he wanted to create a sense of dread. Everything in the story was to build that up.”

“And that’s your basis?”

“For me, the whole unity is what the story tries to convey. It can be heavy-handed. It can be lighthearted. But the characters should reflect that idea by who they are, where they live, how old they are, whether they have family or not, what's the story's tone, what's the crime in the story, and what the murder weapon of the crime is. Everything connects to the whole. I can assess that in my own stories, if I introduce something—an object, a character, a place— I don't just use it once; I use it twice. And if I can't use it twice seamlessly, it's either not important, and thus I don't need to play it up, or it is important because now there's something to that, right? Then, you can begin to explore that. Some editing is for flow, but some ensure this whole thing comes together. Because, you know, readers are going to notice. Clay, you're a fast reader, but you won't read an 80,000-word novel in a night, right?”

“Not unless I have an interview or a story meeting the next day.”

“Right! You'll read that over several days, a week, or something like that.”

“Yes.”

“A short story is something you'll read in twenty minutes or fifteen minutes, and you’ll know if something is off about that story. That's part of the magic of the short story. You’re going to pull off that trick for the reader. You’ve got to grab them. You're not going to have to hold them for long, but any little slip and the magic is gone, and they're out of the story.”

“What unifies the short story? Is it a theme, or what?”

“I tend to think it would be thematic. It would almost have to be. It could be a place, but it must still be about something. Why did you pick the place?”

“Which seems thematic.”

“Yeah, right. You asked the question earlier about how I get started on a story. It’s not some abstract idea. It's not that I want to write about love or family. I think some of that comes out.”

“So what is it?”

“Voice. Voice means two different things. One of them is personal, and one is technical. In terms of your sense of voice, what choices do you make? What do you naturally write about even if you're unaware you're writing about it? What comes up repeatedly in my stories, and I don't intend to do it, is families. Even in stories when it's not necessarily a biological family. I don't know what that says about me. I have great parents. But that tends to be what it is. So, if people can step back in the story and say, ‘Oh, well, this was about love and the price of it,’ then I think I did it.”

“Do you have room in a short story for character arcs?”

“The characters must grow. They must be tested. The structure that I use in most of my stories—I hope it's not obvious, but probably is for people who understand structure—is the three-act structure. So, someone has a problem. That problem has changed their world. And then you get to try to solve the problem, and it gets worse, and it gets worse, and it gets worse. In short stories, it will be a problem you can resolve in 3,000 words, 5,000 words, or 1,000 words if you're writing short. There's going to be moments of conflict. And that's where characterization comes in. Of course, they can't win unless it's a happy story where they win. But how do those setbacks and their trials to set things right—even if it's the wrong decision—go back to the way things were, to embrace a change, and how do they think about that? That's what I like about writing. I think that's where the conflict comes from short stories. That's the story's core: how they will confront it. How does it change them? Does it leave them for the better or worse? And typically, in most of my stories, it’s for the better. Either way, throwing them more problems is the same arc, which'll keep making it more complicated.”

“It keeps building?”

“You can't let the reader rest in a short story, but you can give moments where the character has a little time to reflect. A paragraph, right? ‘Oh, my God, this has happened. Now, what am I going to do?’ So the readers can catch their breath there along with the character, and then back to a million miles an hour. I'll go back to voice. There's the personal side of voice. The words you choose, the topics you choose, even when unaware of those choices. That's your voice. And then there's what I would call narrative voice, which I think is underappreciated as a tool in the short story. The great writers all know how to do it, even if they don't know they're doing it that way. However, one way to achieve compression in a story is not by any of the events you have or don't have; it's how the narrator tells the story. Suppose the narrative voice carries a certain tone, a certain slant, and a certain kind of characterization. In that case, that's going to superpower compression throughout the whole story because people will get the angle that the story is coming from, and then you don't have to explain so much.”

“Easier said than done, of course. So, what are the advantages, if any, of writing short stories over longer forms?”

“They are a wonderful place to experiment. I've written a couple of novels. I would never try to sell them now because I wrote them when I first started writing, and they're not any good. I would have to rewrite them. If I dedicated all my writing to a novel, it’d take me a couple of years to write one. There's no guarantee it would be any good. If my goal is publication, there'd be no guarantee an agent would like it. Then there's no guarantee a publisher would take it or it would sell well; all of those have no guarantees, right? And so, you could get into this thing and have a lot of heartbreak. And then you say, well, I will try it again.”

“And maybe the same thing happens. Trunk novels.”

“With short stories, you can just try it. It's going to take you a few days to write it. I put a lot of angst into the editing bit. A lot of people are better at that than I am. And if it doesn't work, so what? You've talked to yourself a lot about writing. I’ve learned this sort of story isn’t for me, but I'm getting better at it, getting better at it, getting better at it. There's not a lot of money in this stuff. So why not have some fun? Why not experiment?”

“Do you think that writers of short stories have more flexibility in the types of things they can do? And I'm asking this because one of the things I've lamented about the literary industry is that you get known for a certain thing. However, a filmmaker, for example, can make any number of styles of movies, and nobody ever pays attention to the fact. They are usually just attracted to the stars or whoever is in the movie. However, the filmmaker and the writer can be diverse in whatever interests them. Do you think there's more flexibility in being a short story writer?”

“There is. A great example is Jeffrey Deaver.”

“My songwriting buddy.”

“Yes. When he's writing novels, he's Jeffrey Deaver, right? He's the brand and has to deliver a very certain thing. But read some of the short stories. They're terrific. And they're not some of these same characters.”

“Do you think it's difficult for a novelist to write a short story and a short story writer to write a novel? If somebody is used to writing long, can they cut it short? Or can they fill it in after writing short to make it long?”

“You know, people can't be great at everything. Some people are naturally better at short. I suspect I'm one of them. Some people are naturally better at long. But I would also say that if you know how to write, you’ll figure out either form. You can figure out poetry. You can figure out creative nonfiction. If you're a writer, you can write.”

“What’s the most important thing, the most important element, in a short story?”

“Endings are the most important at any length, but short stories are all they are. They exist to give you a big moment of catharsis, release, insight, whatever it is, that you get at the end of a perfect story. Anyone who's a big reader knows what I’m talking about. You get that thing at the end of the story. That's really all short stories are at the end of the day. That's what they're there to do. To produce that moment. And so, I always call it the big honking moment. You light the rocket right at the beginning, and that big honking moment is when the fireworks go off. And it exists to do that and to do it quickly. That's what the payoff and all this planning is about. And people do it in wonderful ways.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. https://claystafford.com/

Robert Mangeot’s short stories have appeared in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, The Forge Literary Magazine, Lowestoft Chronicle, Mystery Magazine, the MWA anthology Ice Cold, and Murder Under the Oaks. His work has been nominated three times for a Derringer Award and, in 2023, received a Killer Nashville Claymore Award. https://robertmangeot.com/

“Dean Koontz: The Secret of Selling 500 Million Books”

Bestselling author Dean Koontz opens up about writing habits, character development, ditching outlines, and what it really takes to sell 500 million books. From 60-hour weeks to honoring eccentricity, Koontz shares advice every aspiring writer should hear.

Dean Koontz interviewed by Clay Stafford

Dean Koontz is and always has been an incredibly prolific writer. He’s also an excellent writer, which explains why he’s had such phenomenal success. When I heard he and I were going to get to chat exclusively for Killer Nashville Magazine, I wanted to talk to him about how one man can author over one hundred and forty books, a gazillion short stories, have sixteen movies made from his books, and sell over five hundred million copies of his books in at least thirty-eight languages. It's no small feat, but surprisingly, one that Dean thinks we are all capable of. “So, Dean, how long should a wannabe writer give their career before they expect decent results?”

“Well, it varies for everybody. But six months is ridiculous. Yeah, it’s not going to be that fast unless you’re one of the very lucky ones who comes out, delivers a manuscript, and publishers want it. But you also have to keep in mind some key things. Publishers don’t always know what the public wants. In fact, you could argue that half the time, they have no idea. A perfect example of this is Harry Potter, which every publisher in New York turned down, and it went to this little Canadian Scholastic thing and became the biggest thing of its generation. So, you just don’t know. But you could struggle for a long time trying to break through, especially for doing anything a little bit different. And everybody says, ‘Well, this is different. Nobody wants something like this.’ And there are all those kinds of stories, so I can’t put a time frame on it. But I would say a minimum of a few years.”

“I usually tell everyone—people who come to Killer Nashville, groups I speak to—four years. Give it four years. Is that reasonable?”

“I think that's reasonable. If it isn’t working in four years, I wouldn’t rule it out altogether, but you’d better find a day job.”

“I was looking at your Facebook page, and it said on some of your books you would work fifty hours a week for x-amount of time, seventy hours a week for x-amount of time. How many hours a week do you actually work?”

“These days, I put in about sixty hours a week. And I’m seventy-eight.”

“Holy cow, you don’t look anywhere near seventy-eight.”

He shakes his head. “There’s no retiring in this. I love what I do, so I’ll keep doing it until I fall dead on the keyboard. There were years when I put in eighty-hour weeks. Now, that sounds grueling. Sixty hours these days probably sounds grueling to most people or to many people. But the fact is, I love what I do, and it’s fun. And if it’s fun, that doesn't mean it’s not hard work and it doesn’t take time, because it’s both fun and hard work, but because it is, the sixty hours fly by. I never feel like I’m in drudgery. So, it varies for everybody. But that’s the time that I put in. When people say, ‘Wow! You’ve written all these books; you must dash them off quickly.’ No, it’s exactly the opposite. But I just put a lot of hours in every week, and it’s that consistency week after week after week. I don’t take off a month for Bermuda. I don't like to travel, so that wouldn't come up anyway. When you do that, it’s kind of astonishing how much work piles up.”

“How is your work schedule divided? I assume you write every single day?”

“Pretty much. I will certainly write six days a week. I get up at 5:00. I used to be a night guy, but after I got married, I became a day guy because my wife is a day person. I’m up at 5:00, take the dog for a walk, feed the dog, shower, and am at my desk by 6:30, and I write straight through to dinner. I never eat lunch because eating lunch makes me foggy, and so I’m looking at ten hours a day, six days a week, and when it’s toward the last third of a book, it goes to seven days a week because the momentum is such that I don’t want to lose it. It usually takes me five months to six months to produce a novel that’s one hundred thousand words.”

“Does this include your editing, any kind of research you do, and all that? Is it in that time period?”

“Yeah, I have a weird way of writing; though, I’ve learned that certain other writers have it. I don’t write a first draft and go back. I polish a page twenty to thirty times, sometimes ten, but I don’t move on from that page until I feel it’s as perfect as I can make it. Then I go to the next page. And I sort of say, I build a book like coral reefs are built, all these little dead skeletons piling on top of each other, and at the end of a chapter, I go print it out because you see things printed out you don’t see on the screen. I do a couple of passes of each chapter that way and then move on. In the end, it’s had so many drafts before anyone else sees it that I generally never have to do much of anything else. I’ll always get editorial suggestions. I think since I started working this way, which was in the early days, my editorial suggestions take me never a lot more than a week, sometimes a couple of days. But when editors make good suggestions, you want to do it because the book does not say ‘By Dean Koontz with wonderful suggestions by…’ You get all the credit, so you might as well take any wonderful suggestion.”

“You get all the blame, too.”

“Yes, you do, although I refuse to accept it.”

“Do you work from an outline, then? Or do you just stream of consciousness?”

“I worked from outline for many years, but things were not succeeding, and so I finally said, you know, one of the problems is that I do an outline, the publisher sees it, says ‘Good. We’ll give you a contract,’ then I go and write the book and deliver it, and it’s not the same book. It’s very similar, but there are all kinds of things, I think, that became better in the writing, and publishers say, ‘Well, this isn’t quite the book we bought,’ and I became very frustrated with that. I also began to think, ‘This is not organic. I am deciding the entire novel before I start it.’ Writing from an outline might work and does for many writers, but I realized it didn’t work for me because I wasn’t getting an organic story. The characters weren’t as rich as I wanted because they were sort of set at the beginning. So, I started writing the first book I did without an outline called Strangers, which was over two hundred fifty thousand words. It was a long novel and had about twelve main characters. It was a big storyline, and I found that it all fell together perfectly well. It took me eleven months of sixty- to seventy-hour weeks, but the book came together, and that was my first hardcover bestseller. I’ve never used an outline since. I just begin with a premise, a character or two, and follow it all. It’s all about character, anyway. If the book is good, character is what drives it.”

“Is that the secret of it all? Putting in the time? Free-flowing thought? Characters?”

“I think there are several. It’s just willing to put in the time and think about what you’re doing, recognizing that characters are more important than anything else. If the characters work, the book will work. If the characters don’t, you may still be able to sell the book, but you’re not looking at long-term reader involvement. Readers like to fall in love with the characters. That doesn’t mean the characters all have to be wonderful angelic figures. They also like to fall in love with the villains, which means getting all those characters to be rich and different. I get asked often, ‘You have so many eccentric characters. The Odd Thomas books are filled with almost nothing else. How do you make them relatable?’ And I say, ‘Well, first, you need to realize every single human being on the planet is eccentric. You are as well.”

“Me?” I laugh. “You’re the first to point that out.”

He joins in. “It’s just a matter of recognizing that. And then, when you start looking for the characters’ eccentricities—which the character will start to express to you—you have to write them with respect and compassion. You don’t make fun of them, even if they are amusing, and you treat them as you would people: by the Golden Rule. And if you do, audiences fall in love with them, and they stay with you to see who you will write about next. And that’s about the best thing I can say. Don’t write a novel where the guy’s a CIA agent, and that’s it. Who is he? What is he other than that? And I never write about CIA agents, but I see there’s a tendency in that kind of fiction to just put the character out there. That’s who he is. Well, that isn’t who he is. He’s something, all of us are, something much more than our job.”

“What advice do you give to new writers who want to become the next Dean Koontz?”

“First of all, you can’t be me because I’m learning to clone myself, so I plan to be around for a long time. But, you know, everybody works a different way, so I’m always hesitant to give ironclad advice. But what I do say to many young writers who write to me, and they’ve got writer's block, is that I’ve never had it, but I know what it is. It’s always the same thing. It’s self-doubt. You get into a story. You start doubting that you can do this, that this works, that that works. It’s all self-doubt. I have more self-doubt than any writer I’ve ever known, and that’s why I came up with this thing of perfecting every page until I move to the next. Then, the self-doubt goes away because the page flows, and when I get to the next page, self-doubt returns. So, I will do it all again. When I’m done, the book works. Now, if that won’t work for everybody, I think it could work for most writers if they get used to it, and there are certain benefits to it. You do not have to write multiple drafts after you’ve written one. What happens with a lot of writers is they write that first draft—especially when they’re young or new—and now they have something, and they’re very reluctant to think, ‘Oh, this needs a lot of work’ because they’re looking at it as, ‘Oh, I have a novel-length manuscript.’ Well, that’s only the first part of the journey. And I just don’t want to get to that point and feel tempted to say, ‘This is good enough,’ because it almost never will be that way.”

“No,” I say, “it never will.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. https://claystafford.com/

Dean Koontz is the author of many #1 bestsellers. His books have sold over five hundred million copies in thirty-eight languages, and The Times (of London) has called him a “literary juggler.” He lives in Southern California with his wife Gerda, their golden retriever, Elsa, and the enduring spirits of their goldens Trixie and Anna. https://www.deankoontz.com/

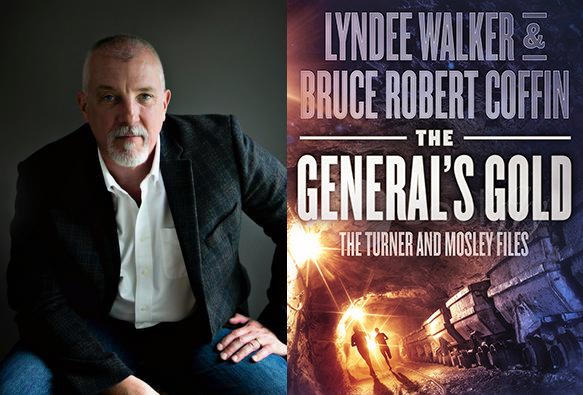

“Bruce Robert Coffin: Using Your Life to Write a Police Procedural”

Bruce Robert Coffin, retired detective turned bestselling author, shares how real police work shapes compelling fiction. From emotional authenticity to procedural accuracy, Coffin reveals what it really takes to write a great police procedural—and how any writer can get it right.

Bruce Robert Coffin interviewed by Clay Stafford

Bruce Robert Coffin has been coming to Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference every year since its early days, so it’s only fitting that we feature this incredibly talented writer as our cover story. To give a little backstory, Bruce wanted to be a writer, but after going to college and not necessarily receiving the encouragement or success he had hoped for, he chose a career in law enforcement. Little did he realize he was laying the foundation for the outstanding writing career that was to follow. I had a chance to speak with Bruce from his home in Maine. “Bruce, when you were a police officer, a detective, did you even think about writing again, or did you miss writing as you went through your regular job?”

“There’s nothing fun about writing in police work or detective work. Everything is bare bones. There’s not much room for adjectives or that type of stuff. It’s just the facts, ma’am. That’s what they expect out of you. So, everything is boilerplate. It’s very boring. You’re taking statements all the time. You’re writing. If there was one similar thing, and it certainly didn’t occur to me that there would ever be a time that I would write fiction again, but it did teach me to write cohesively. Everything that we did had to make sense. You know, you do one thing before you do the next. Building timelines for putting a case together, doing interviews with witnesses, and then figuring out how they all fit together, and making a cohesive story or narrative out of that to explain to a judge, a jury, or a prosecutor. As far as story building was concerned, I think that might have been something I was learning at that point because that’s exactly how a real case gets made. I wasn’t thinking about it in terms of writing later, but I think it’s something that helped me because I think my brain works that way now. I know how cases will work, I know how cases are solved, and I know why cases stall out. I think all those things really allow me to better describe what real police work is like in my fictional novels.”

“When you retired from detective work and started writing again, how much of the police work transferred over, and how much was fiction from your head?”

“I made a deal with myself when I started that I wouldn’t write anything based on a real case. I had had enough of true crime. I had seen what the real-life cases had done to people: the survivors, the victims, the families, and I didn’t want to do anything that would cause people pain by fictionalizing something that had been part of their lives. I made a deal with myself that I would write as realistically as possible, but I would never base any books on an actual case I had worked on. And I’ve so far, knock on wood, been able to stand by that. I think the only exception would be if it were something that had a reason. Maybe the family came to me and asked me to do that or something like that. There had to be a reason for it, though. And so, when I started writing, I could draw from a well of a million experiences, things that we tamp down deep inside, and you don’t think about how that affects who I am and how I see the world. And I think in my mind, I imagined I would be making up stuff, and that would be it. There’s nothing but my imagination. There would be nothing personal about what I was writing, and it would just be fun. And like everything you delve into that you don’t actually know, I had no idea I would be diving into the real stuff, like dipping the ladle into that emotional well and pulling out chunks of things from my past. There were scenes that I wrote that emotionally moved me as I was writing them. And it’s because what I’m writing is based on something that happened in real life. And I’m crafting it to fit into the narrative of the story I’m writing. But the goal of me doing that is really to evoke emotion from the reader, which I think is the most important thing any of us can do. You want the reader to feel something. You want them to be lost in your story. And I really didn’t think that was going to happen. But it’s amazing what I dredged up and continued to dredge up as I write these fictional police procedural stories.”

“Some of the writers I talk with view writing as therapy. Did you find it cathartic coming from your previous life?”

“I did. I think that was another shock. I didn’t think any catharsis was involved in what I was doing. But like I say, when you start delving back into things that you thought you had either forgotten about or thought were long past, it really allowed me to deal with things. It allowed me to deal with things I wasn’t happy about when I left the job. The things that I wish I could unsee or un-experience. As a writer, I was able to pull from those. I think you and I have talked about this in the past. I honestly think the best writing comes from adversity. Anything difficult that the writers have gone through in life translates well to the page. And I think that’s one of those things where, if you can insert those moments into your characters’ lives, your reader can’t help but identify with them. So, I just had the luxury of having the life we all have, the ups and downs, the highs and lows, the death and the love, and all those things we have to experience. But added to that, I had thirty years of a crazy front-row seat to the world as a law enforcement officer. So, using all of that, I think, has made my stories much more realistic and maybe more entertaining because it gives the reader a glimpse inside what that world is really like.”

“So, you have this front-row seat. And then we readers read that, and we want to write that. But we haven’t had that experience. Is it even possible for us to get to that point that we could write something like that?”

“It is. And I tell people that all the time. I say you have to channel your experiences differently, I think. Like I said, we all have experiences, things that are heart-wrenching, or things that are horrifying, or whatever it is in our lives. They just don’t happen with as great a frequency as they would happen for a police officer. And we all know what it’s like to be frustrated working for a business, being part of a dysfunctional family, or whatever it is. Everybody has something. And so, I tell people to use that. Use that in your stories and try to imagine. You know, you can learn the procedure. You might not have those real-world experiences, but you can learn the procedure, especially from reading other writers who do it well. But use your own experiences. Insert that in there. You know, one of the things that I think is the easiest for people to think about is how hard it is to try and hold down a job. Like, you go to work, and you may see the most horrific murder happen, and you’re dealing with the angst that the family or witness is suffering, and you’re carrying that with you. Then you come home and try to deal with a real-world where other people don’t see that stuff. Like your spouse is worried that the dishwasher is leaking water under the kitchen floor, and that’s the worst thing that’s happened all day, right? That the house is stressed out because of that. And it’s hard to come home. It’s almost like you have to lead a split personality. It’s hard to come home and show the empathy that your spouse needs for that particular tragedy when you’re carrying all those other tragedies from the day. And you won’t share those with them because you don’t want that darkness in your house. I tell people to try to envision what that would be like and then pull from their own life the adversity they’ve experienced or seen and use that to make the story and the characters real. You can steal the procedure from good books. Get to know your local law enforcement officer, somebody who’s actually squared away and will share that information with you. Don’t get it from television necessarily. Some of TV writing is laziness. Some of it’s because they have a very short time constraint to try and get the story told. So, they take huge liberties with reality. But if you can take that stuff and try to put yourself in the shoes of the detective and use your own experiences, you can bring a detective to life.”

“You think anybody can do it?”

“I do. I do think that you have to pull from the right parts of your life. And again, as I say, if you spend enough time with somebody who’s done the job and get them to tell you, it’s not just what we do. It’s how we feel. And the feeling, I think, is what’s missing from those stories many times. If you want to tell a real gritty police detective story, you have to have feeling in that. That’s the one thing we all pretend we don’t have. You know, we keep the stone face. We go to work, do our thing, and pretend to be the counselor or the person doing the interrogation. But at the end of the day, we’re still just human beings. And we’re absorbing all these things like everybody else does. So yeah, you have to see that. Get to hear that from somebody for real, and you’ll know what will make your detective tick.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. https://claystafford.com/

Bruce Robert Coffin is an award-winning novelist and short story writer. A retired detective sergeant, Bruce is the author of the Detective Byron Mysteries, co-author of the Turner and Mosley Files with LynDee Walker, and author of the forthcoming Detective Justice Mysteries. His short fiction has appeared in a dozen anthologies, including Best American Mystery Stories, 2016. http://www.brucerobertcoffin.com/

“A Casual Conversation with Susan Isaacs”

In this informal and delightful follow-up conversation with bestselling author Susan Isaacs, we chat about writing description, plotting mysteries, working with ADHD, and how building a fictional series can feel like creating a second family. A refreshing reminder of why writers write—and why conversations like this matter.

Susan Isaacs interviewed by Clay Stafford

I had a wonderful opportunity to just chat with bestselling author and mystery legend, Susan Isaacs, as a follow-up to my interview with her for my monthly Writer’s Digest column. It was a wonderful conversation. I needed a break from writing. She needed a break from writing. Like a fly on the wall (and with Susan’s permission), I thought I’d share the highlights of our conversation here with you.

“Susan, I just finished Bad, Bad, Seymore Brown. I loved it. And I now have singer Jim Croce’s earworm in my head.”

“Me, too.” She laughed.

“I love your descriptions in your prose. Right on the mark. Not too much, not too little.”

“Description can be hard.”

“But you do it so well. Any tips?”

“Well, I’ll tell you what I do. Two things. First, I see it in my head. I’m looking at the draft, and I say, ‘Hey, you know, there’s nothing here.’”

I laugh. “So, what do you do?”

“Well in Bad, Bad, Seymore Brown, the character with the problem is a college professor, a really nice woman, who teaches film, and her area of specialization is big Hollywood Studio films. When she was five, her parents were murdered. It was an arson murder, and she was lucky enough to jump out of the window of the house and save herself. So, Corie, who’s my detective, a former FBI agent, is called on, but not through herself, but through her dad, who’s a retired NYPD detective. He was a detective twenty years earlier, interviewing this little girl, April is her name, and they kept up a kind of birthday-card-Christmas-card relationship.”

“And the plot is great.”

“Thanks, but in terms of description, there was nothing there. But there were so many things to work with. So, after I get that structure, I see it in my head, and I begin to type it in.”

“The description?”

“Plot, then description.”

“And you mentioned another thing you do?”