KN Magazine: Interviews

Clay Stafford talks with Paul Karasik on “How to Write a Graphic Novel”

Two-time Eisner Award winner Paul Karasik joins Clay Stafford to discuss how to write a graphic novel—how to think visually, collaborate with artists, and translate emotion into panels. A masterclass in visual storytelling from one of comics’ most insightful minds.

Paul Karasik interviewed by Clay Stafford

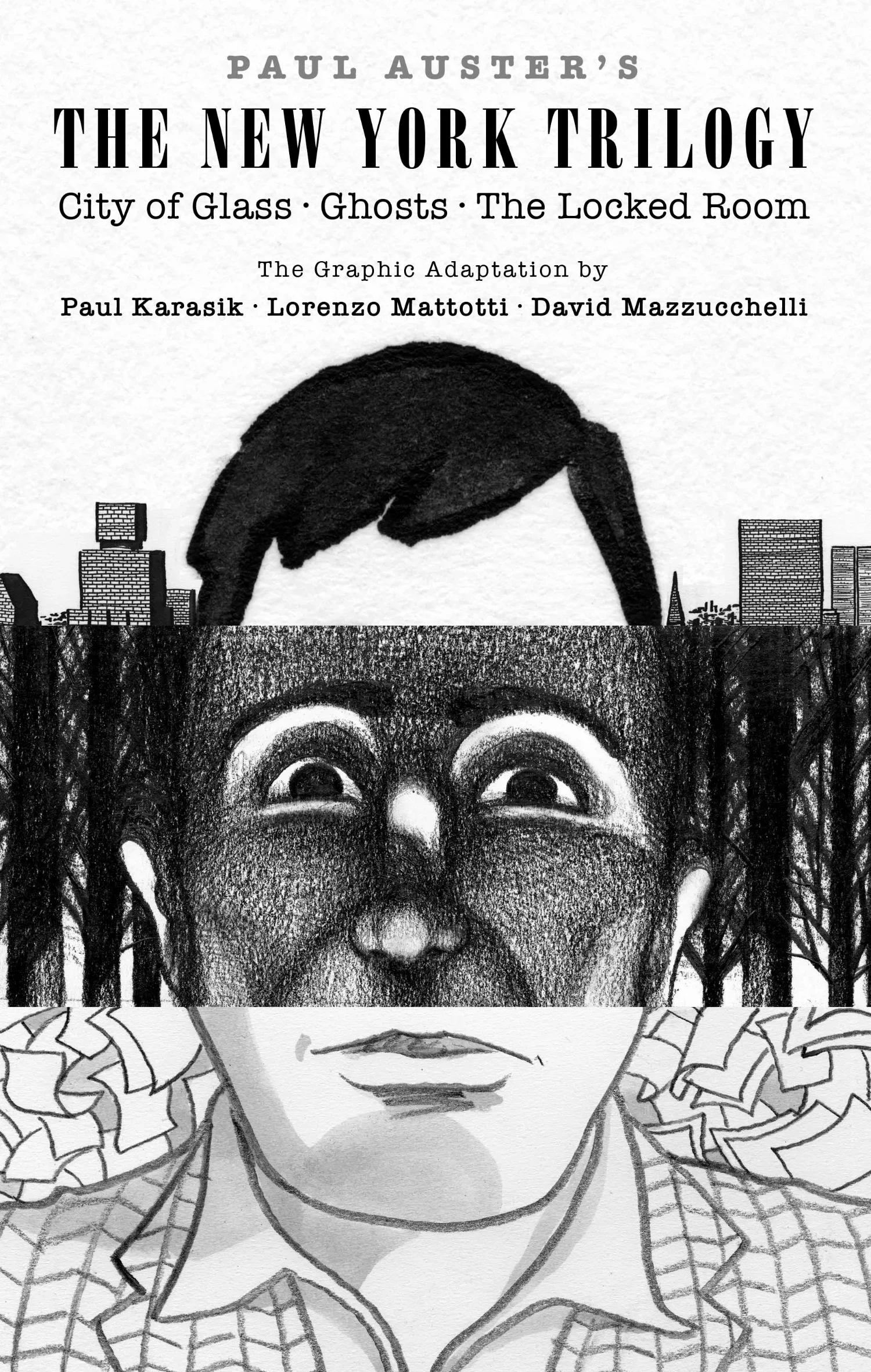

In the world of graphic storytelling, few figures bridge scholarship, craft, and creativity as seamlessly as Paul Karasik. A two-time Eisner Award winner, Karasik’s career has spanned from his early days as Associate Editor at RAW, the influential magazine founded by Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly, to adaptations of literary works that redefined what comics could do. His collaborations include The New York Trilogy, the acclaimed visual deconstruction How to Read Nancy (co-written with Mark Newgarden), and the memoir The Ride Together, written with his sister about growing up alongside their brother with autism.

Karasik is not simply an artist who draws or a writer who scripts. He’s a thinker who dissects how meaning is built through image, rhythm, and restraint. His teaching has influenced a generation of visual storytellers to approach comics as architecture: design, intention, and emotional subtext all working in tandem. In this conversation, I spoke with Paul about how to write a graphic novel: how to think in images, collaborate with artists, structure the visual page, and find the emotional heartbeat that turns panels into story. What follows is a masterclass in how words and pictures meet, and how purpose turns craft into art.

“Paul, let’s say I’ve decided to write a graphic novel, and I don’t know where to start. I’m not trying to sell it or anything; I just want to write it. I’ve heard that you need to think in scenes, not paragraphs. I’m not sure exactly what that means.”

“It’s more like screenwriting. Because it’s a visual medium, you really need to have a clear picture in your head of what everything looks like and how the space is laid out. Draw a little blueprint of what’s happening in any given scene so the characters move consistently through that space. The sofa is always to the left of the dining room table, or whatever. You need to have that visual sense.”

“So, in a way, the writer is the director, and the graphic realization comes from working with an artist, just as the filmic realization comes from working with a cinematographer. Is that a good analogy?”

“Absolutely. That’s a fine analogy. You’re engaging in a collaborative art. You’re working with an artist whom you may not have met yet, so you have to develop a relationship that allows for interpretation. Ideally, you find someone you can continue to work with. Ingmar Bergman is a great director, but Sven Nykvist was his cinematographer. Bergman’s movies always look like Bergman’s movies. You need that same strong sense of what the whole thing will look like and what its emotional core is. What’s the point? There’s the text, and then there’s the subtext. If you’re not addressing the subtext, you might as well be writing ad copy. One of the things I tell my students is that in a graphic novel, you don’t have a lot of space for dialogue. Your first draft can be verbose because you’re figuring out what the character needs to say. But once you know that, it has to be boiled down to ten words or less. You can’t have people going on for three paragraphs, or even three sentences. Two sentences max in a word balloon. There just isn’t that much space, and you don’t need it because the picture is doing the bulk of the work. So, two rules for dialogue: keep it short and keep it to the point. And every time a character speaks, that dialogue has to do two things. It has to reveal something about who that character is, and it has to move the plot forward. Even if a character says, ‘I don’t know,’ it should still be part of the story’s engine.”

“So, the old ‘show, don’t tell’ is really important in a graphic novel.”

“Absolutely. What you show and how you show it matters. Every panel is a composition, and the way it’s read, top to bottom, left to right, is storytelling.”

“When you’re writing it, you’re writing the panel descriptions as well as the dialogue, correct?”

“Every panel.”

“How do you determine, on a page, how many frames or panels you’re using? Does the writer decide that?”

“Here’s another really good reason to go to the bookstore and find a book that feels like it has the same kind of weight or tone as your own vision. Look at it. Does it have three tiers or four? How many panels per tier? How many words per page? Do the counting, and then model your writing after that. Even if your story isn’t the same genre, say, you’re writing something that’s going to be banned instead of a silly macho space fantasy that won’t be, it’s a good exercise.”

“The first and second stories of your New York Trilogy, they’re completely different. The first has smaller panels throughout, and the next has a large panel with a lot of writing underneath.”

“The very first lesson in my Graphic Novel Lab would be that form follows function. You have to understand what your story is about, and then figure out what the form should be. In the first book of The New York Trilogy, the layout is a nine-panel grid. Over the course of the story, the main character, who pretends to be a detective, becomes obsessed, loses his apartment, his past life, and eventually his mind. What that story is really about is the nature of fiction itself. If this coffee cup isn’t called a coffee cup, is it still a coffee cup? At the start, the layout is rigid, every page in that nine-panel grid. By the end, as the character unravels, the gutters between panels widen, the panels stop being drawn with a ruler, and they start to wiggle. As he loses his grip on reality, the comic itself becomes unglued until the panels fall off the page. That’s why it’s designed that way. In the second book, the layout looks more like an illustrated text, an image on top, words beneath. It’s still a detective story, but this one is really about reading fiction. The detective has never read anything in his life. When he tries to read Walden, he can’t. He only knows how to read for facts. So when we reach that moment in the book, the layout itself changes. The pages turn into comics panels, forcing the reader to experience a different kind of reading. Then we switch back again. The format shifts to underscore the subtext: you can read passively, or we can make you read actively.”

“There’s not a lot of space. You’ve got action, a little dialogue, and you have to keep internal monologue to a limit, don’t you?”

“Not necessarily. Thought balloons and narrative blocks can serve as exposition when needed, but everything should support the story. You need to know your story, your plot, and your subtext before designing your comic. It may sound intimidating, but once you learn to think like a cartoonist, it becomes natural. That’s what I teach: a way of thinking.”

“Let’s talk about setting.”

“The setting and environment are essential. In the first book of The New York Trilogy, New York City is as much a character as the protagonist. In the second book, less so. By the third, the story hardly mentions New York at all, yet you still know where you are. So, yes, establish the world early. Don’t make the reader guess whether they’re in a space capsule or a time capsule. Do them a favor.”

“As a writer who writes for directors, I’m always careful not to cross that creative line. For the writer sitting at the desk putting this together, what’s the line they shouldn’t cross when working with a graphic artist?”

“Every collaboration is different. Think again of Bergman and Nykvist. At first, there was probably a lot of back-and-forth. But once a relationship is built, each trusts the other’s instincts. For the books I’ve worked on, I’ve done the sketches and scripts myself because I can draw. Both artists I’ve worked with collaborated closely to bring those sketches to life and then did the finished art. The best relationships are built on mutual respect. You find an artist whose style fits your vision, and you trust each other.”

“You’ve mentioned that your projects often find you, rather than the other way around. As a parting thought, can you talk about that passion? What turns a project from work-for-hire into something driven by obsession?”

“I have a peculiar career because I don’t do just one thing. I adapted Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy, co-wrote How to Read Nancy with Mark Newgarden, and wrote a memoir with my sister about growing up with our brother, who had autism, The Ride Together. None of these were projects I consciously chose. They demanded to be made. When I try to invent something just to invent it, I can tell when it’s hollow. The real ones insist on being created. It’s instinctual. I don’t have a choice. It’s compulsion, obsession. That’s how I’m built. Don’t start a graphic novel thinking you’ll sell it immediately, and don’t do it just because you liked Spider-Man as a kid. Do it because you can’t possibly do anything else. It’s what you were meant to do.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of the Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference, Killer Nashville Magazine, and the Killer Nashville University streaming service. Subscribe to his newsletter at https://claystafford.com/.

Two-time Eisner Award winner Paul Karasik began his career as the Associate Editor of Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly’s RAW magazine. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The New Yorker.

https://www.paulkarasikcomics.com/

Author photo credit: Ray Ewing

Submit Your Writing to KN Magazine

Want to have your writing included in Killer Nashville Magazine?

Fill out our submission form and upload your writing here: