KN Magazine: Interviews

Clay Stafford talks with Joyce Carol Oates “On Being Her Own Person”

In this conversation, Joyce Carol Oates reflects on her new collection Flint Kill Creek, the evolving political relevance of her historical novel Butcher, and her enduring drive to experiment across genres. With insight into her writing process, teaching philosophy, and thoughts on literary career-building, Oates offers rare wisdom for writers navigating both inspiration and discipline.

Joyce Carol Oates interviewed by Clay Stafford

I first met Joyce Carol Oates when she was the John Seigenthaler Legends Award winner at the Killer Nashville International Writer’s Conference. She is a prolific writer, a modern-day legend, and a professor at NYU and Princeton, where her fortunate students learn from one of the best living writers today. When her new collection of short stories came out, Flint Kill Creek, I reached out to her to see if we could chat about the new book, writing in general, and how to prepare oneself for a career as a writer. My goal, because she is both a prolific writer and a teacher, was to see if there was some Holy Grail that writers could discover to create a successful career. Fortunately, we may have stumbled upon it. “Joyce, someone such as you who's written over a hundred books, how do you consistently generate these fresh ideas and maintain this creative energy you've got going?”

“Well, it would not interest me to write the same book again, so I wouldn't be interested in that at all.”

“I wonder if some of it also has to do with all the reading you do. It's generating new ideas coming in all the time.”

“I suppose so. That's just the way our minds are different. I guess there are some writers who tend to write the same book. Some people have fixations about things. I don't know how to assess my own self, but I'm mostly interested in how to present the story in terms of structure. Like Flint Kill Creek, the story is really based very much on the physical reality of a creek: how, in a time of heavy rainfall, it rises and becomes this rushing stream. Other times, it's sort of peaceful and beautiful, and you walk along it, yet it's possible to underestimate the power of some natural phenomenon like a creek. It's an analog with human passion. You think that things are placid and in control, but something triggers it, and suddenly there is this violent upheaval of emotion. The story is really about a young man who is so frightened of falling in love or losing control, he has to have a kind of adversarial relationship with young women. He's really afraid to fall in love because it's like losing control. So, through a series of incidents, something happens so that he doesn't have to fall in love, that the person he might love disappears from the story. But to me, the story had to be written by that creek. I like to walk myself along the towpath here in the Princeton area, the Delaware and Raritan Canal. When I was a little girl, I played a lot in Tonawanda Creek, I mean literally played along with my friends. We would go down into the creek area and wade in the water, and then it was a little faster out in the middle, so it was kind of playful, but actually a little dangerous. Then, after rainfall, the creek would get very high and sometimes really high. So it's rushing along, and it's almost unrecognizable. I like to write about the real world, and describe it, and then put people into that world.”

“You've been writing for some time. How do you keep your writing so relevant and engaging to people at all times?”

“I don't know how I would answer that. I guess I'm just living in my own time. My most recent novel is called Butcher, and I wrote it a couple of years ago, and yet now it's so timely because women's reproductive rights have been really under attack and have been pushed back in many states, and it seems that women don't have the rights that we had only a decade ago, and things are kind of going backwards. So, my novel Butcher is set in the 19th century, and a lot of the ideas about women and women's bodies almost seem to be making like a nightmare comeback today. I was just in Milan. I was interviewed a lot about Butcher, and earlier in the year I was in Paris, and I was interviewed about Butcher, because the translations are coming out, and the interviewers were making that connection. They said, ‘Well, your novel is very timely. Was this deliberate?’ And I'm not sure if it was exactly deliberate, because I couldn't foretell the future, but it has this kind of painful timeliness now.”

“How do you balance your writing with all this marketing? Public appearances? Zoom meetings with me? How do you get all of it done? How does Joyce Carol Oates get all of it done?”

“Oh, I have a lot of quiet time. It's nice to talk to you, but as I said, I was reading like at 7 o'clock in the morning, I was completely immersed in a novel, then I was working on my own things, and then talking with you from three to four, that's a pleasure. It's like a little interlude. I don't travel that much. I just mentioned Milan and Paris because I was there. But most of the time I'm really home. I don't any longer have a husband. My husband passed away, so the house is very quiet. I have two kitties, and my life is kind of easy. Really, it's a lonely life, but in some ways it's easy.”

“Do you ever think at all—at the level you're at—about any kind of expanded readership or anything? Or do you just write and throw it out there?”

“I wouldn't really be thinking about that. That's a little late in my career. I mean, I try to write a bestseller.”

“And you have.”

“My next novel, which is coming out in June, is a whodunnit.”

“What's the title?”

“Fox, a person is named Fox. That's the first novel I've ever written that has that kind of plot. A body's found, there’s an investigation, we have back flash and backstory, people are interviewed. You follow about six or seven people, and one of them is actually the murderer, and you find out at the end who the murderer is. The last chapter reveals it. It's sort of like a classic structure of a whodunnit, and I've never done that before. I didn't do it for any particular reason. I think it was because I hadn't done it before, so I could experiment, and it was so much fun.”

“That's one of the things readers love about your work, is you experiment a lot.”

“That was a lot of fun, because I do read mysteries, and yet I never wrote an actual mystery before.”

“Authors sometimes get the advice—which you're totally the exception to—of pick one thing, stay with it, don’t veer from that because you can't build a brand if you don't stick with that one thing. Yet you write plays, nonfiction, poetry, short stories, novels, and you write in all sorts of genres. What advice or response do you give to that? Because I get that ‘stick with one thing’ all the time from media experts at Killer Nashville. You're the exception. You don't do that.”

“No, but I'm just my own person. I think if you want to have a serious career, like as a mystery detective writer, you probably should establish one character and develop that character. One detective, let's say, set in a certain region of America so that there's a good deal of local color. I think that's a good pattern to choose one person as a detective, investigator, or coroner and sort of stay with that person. I think most people, as it turns out, just don't have that much energy. They're not going to write in fifteen different modes. They're going to write in one. So that's sort of tried and true. I mean, you know Ellery Queen and Earl Stanley Gardner and Michael Connolly. Michael Connolly, with Hieronymus Bosch novels, is very successful, and they're excellent novels. He's a very good writer. He's made a wonderful career out of staying pretty close to home.”

“Is there any parting advice you would give to writers who are reading here?”

“I think the most practical advice, maybe, is to take a writing course with somebody whom you respect. That way you get some instant feedback on your writing, and I see it all the time. The students are so grateful for ideas. I have a young woman at Rutgers, she got criticism from the class, and she came back with a revision that was stunning to me. I just read it yesterday. Her revision is so good, I think my jaw dropped. She got ideas from five or six different people, including me. I gave her a lot of ideas. She just completely revised something and added pages and pages, and I was really amazed. I mean, what can I say? That wouldn't have happened without that workshop. She knows that. You have to be able to revise. You have to be able to sit there and listen to what people are saying, and take some notes, and then go home and actually work. She is a journalism major as well as something else. So I think she's got a real career sense. She’s gonna work. Other people may be waiting for inspiration or something special, but she's got the work ethic. And that's important.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference and the online streaming creative learning platform The Balanced Writer. Subscribe to his weekly writing tips at https://claystafford.com/

Joyce Carol Oates has published nearly 100 books, including 58 novels, many plays, novellas, volumes of short stories, poetry, and non-fiction. Her novels Black Water, What I Lived For, and Blonde were finalists for the Pulitzer Prize; she won the National Book Award for her novel them. https://celestialtimepiece.com/

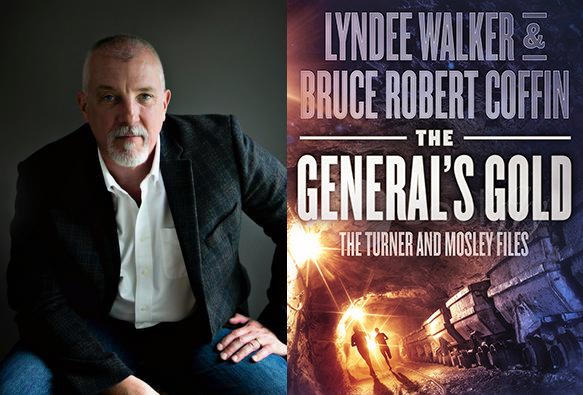

“Bruce Robert Coffin: Using Your Life to Write a Police Procedural”

Bruce Robert Coffin, retired detective turned bestselling author, shares how real police work shapes compelling fiction. From emotional authenticity to procedural accuracy, Coffin reveals what it really takes to write a great police procedural—and how any writer can get it right.

Bruce Robert Coffin interviewed by Clay Stafford

Bruce Robert Coffin has been coming to Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference every year since its early days, so it’s only fitting that we feature this incredibly talented writer as our cover story. To give a little backstory, Bruce wanted to be a writer, but after going to college and not necessarily receiving the encouragement or success he had hoped for, he chose a career in law enforcement. Little did he realize he was laying the foundation for the outstanding writing career that was to follow. I had a chance to speak with Bruce from his home in Maine. “Bruce, when you were a police officer, a detective, did you even think about writing again, or did you miss writing as you went through your regular job?”

“There’s nothing fun about writing in police work or detective work. Everything is bare bones. There’s not much room for adjectives or that type of stuff. It’s just the facts, ma’am. That’s what they expect out of you. So, everything is boilerplate. It’s very boring. You’re taking statements all the time. You’re writing. If there was one similar thing, and it certainly didn’t occur to me that there would ever be a time that I would write fiction again, but it did teach me to write cohesively. Everything that we did had to make sense. You know, you do one thing before you do the next. Building timelines for putting a case together, doing interviews with witnesses, and then figuring out how they all fit together, and making a cohesive story or narrative out of that to explain to a judge, a jury, or a prosecutor. As far as story building was concerned, I think that might have been something I was learning at that point because that’s exactly how a real case gets made. I wasn’t thinking about it in terms of writing later, but I think it’s something that helped me because I think my brain works that way now. I know how cases will work, I know how cases are solved, and I know why cases stall out. I think all those things really allow me to better describe what real police work is like in my fictional novels.”

“When you retired from detective work and started writing again, how much of the police work transferred over, and how much was fiction from your head?”

“I made a deal with myself when I started that I wouldn’t write anything based on a real case. I had had enough of true crime. I had seen what the real-life cases had done to people: the survivors, the victims, the families, and I didn’t want to do anything that would cause people pain by fictionalizing something that had been part of their lives. I made a deal with myself that I would write as realistically as possible, but I would never base any books on an actual case I had worked on. And I’ve so far, knock on wood, been able to stand by that. I think the only exception would be if it were something that had a reason. Maybe the family came to me and asked me to do that or something like that. There had to be a reason for it, though. And so, when I started writing, I could draw from a well of a million experiences, things that we tamp down deep inside, and you don’t think about how that affects who I am and how I see the world. And I think in my mind, I imagined I would be making up stuff, and that would be it. There’s nothing but my imagination. There would be nothing personal about what I was writing, and it would just be fun. And like everything you delve into that you don’t actually know, I had no idea I would be diving into the real stuff, like dipping the ladle into that emotional well and pulling out chunks of things from my past. There were scenes that I wrote that emotionally moved me as I was writing them. And it’s because what I’m writing is based on something that happened in real life. And I’m crafting it to fit into the narrative of the story I’m writing. But the goal of me doing that is really to evoke emotion from the reader, which I think is the most important thing any of us can do. You want the reader to feel something. You want them to be lost in your story. And I really didn’t think that was going to happen. But it’s amazing what I dredged up and continued to dredge up as I write these fictional police procedural stories.”

“Some of the writers I talk with view writing as therapy. Did you find it cathartic coming from your previous life?”

“I did. I think that was another shock. I didn’t think any catharsis was involved in what I was doing. But like I say, when you start delving back into things that you thought you had either forgotten about or thought were long past, it really allowed me to deal with things. It allowed me to deal with things I wasn’t happy about when I left the job. The things that I wish I could unsee or un-experience. As a writer, I was able to pull from those. I think you and I have talked about this in the past. I honestly think the best writing comes from adversity. Anything difficult that the writers have gone through in life translates well to the page. And I think that’s one of those things where, if you can insert those moments into your characters’ lives, your reader can’t help but identify with them. So, I just had the luxury of having the life we all have, the ups and downs, the highs and lows, the death and the love, and all those things we have to experience. But added to that, I had thirty years of a crazy front-row seat to the world as a law enforcement officer. So, using all of that, I think, has made my stories much more realistic and maybe more entertaining because it gives the reader a glimpse inside what that world is really like.”

“So, you have this front-row seat. And then we readers read that, and we want to write that. But we haven’t had that experience. Is it even possible for us to get to that point that we could write something like that?”

“It is. And I tell people that all the time. I say you have to channel your experiences differently, I think. Like I said, we all have experiences, things that are heart-wrenching, or things that are horrifying, or whatever it is in our lives. They just don’t happen with as great a frequency as they would happen for a police officer. And we all know what it’s like to be frustrated working for a business, being part of a dysfunctional family, or whatever it is. Everybody has something. And so, I tell people to use that. Use that in your stories and try to imagine. You know, you can learn the procedure. You might not have those real-world experiences, but you can learn the procedure, especially from reading other writers who do it well. But use your own experiences. Insert that in there. You know, one of the things that I think is the easiest for people to think about is how hard it is to try and hold down a job. Like, you go to work, and you may see the most horrific murder happen, and you’re dealing with the angst that the family or witness is suffering, and you’re carrying that with you. Then you come home and try to deal with a real-world where other people don’t see that stuff. Like your spouse is worried that the dishwasher is leaking water under the kitchen floor, and that’s the worst thing that’s happened all day, right? That the house is stressed out because of that. And it’s hard to come home. It’s almost like you have to lead a split personality. It’s hard to come home and show the empathy that your spouse needs for that particular tragedy when you’re carrying all those other tragedies from the day. And you won’t share those with them because you don’t want that darkness in your house. I tell people to try to envision what that would be like and then pull from their own life the adversity they’ve experienced or seen and use that to make the story and the characters real. You can steal the procedure from good books. Get to know your local law enforcement officer, somebody who’s actually squared away and will share that information with you. Don’t get it from television necessarily. Some of TV writing is laziness. Some of it’s because they have a very short time constraint to try and get the story told. So, they take huge liberties with reality. But if you can take that stuff and try to put yourself in the shoes of the detective and use your own experiences, you can bring a detective to life.”

“You think anybody can do it?”

“I do. I do think that you have to pull from the right parts of your life. And again, as I say, if you spend enough time with somebody who’s done the job and get them to tell you, it’s not just what we do. It’s how we feel. And the feeling, I think, is what’s missing from those stories many times. If you want to tell a real gritty police detective story, you have to have feeling in that. That’s the one thing we all pretend we don’t have. You know, we keep the stone face. We go to work, do our thing, and pretend to be the counselor or the person doing the interrogation. But at the end of the day, we’re still just human beings. And we’re absorbing all these things like everybody else does. So yeah, you have to see that. Get to hear that from somebody for real, and you’ll know what will make your detective tick.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. https://claystafford.com/

Bruce Robert Coffin is an award-winning novelist and short story writer. A retired detective sergeant, Bruce is the author of the Detective Byron Mysteries, co-author of the Turner and Mosley Files with LynDee Walker, and author of the forthcoming Detective Justice Mysteries. His short fiction has appeared in a dozen anthologies, including Best American Mystery Stories, 2016. http://www.brucerobertcoffin.com/

“A Casual Conversation with Susan Isaacs”

In this informal and delightful follow-up conversation with bestselling author Susan Isaacs, we chat about writing description, plotting mysteries, working with ADHD, and how building a fictional series can feel like creating a second family. A refreshing reminder of why writers write—and why conversations like this matter.

Susan Isaacs interviewed by Clay Stafford

I had a wonderful opportunity to just chat with bestselling author and mystery legend, Susan Isaacs, as a follow-up to my interview with her for my monthly Writer’s Digest column. It was a wonderful conversation. I needed a break from writing. She needed a break from writing. Like a fly on the wall (and with Susan’s permission), I thought I’d share the highlights of our conversation here with you.

“Susan, I just finished Bad, Bad, Seymore Brown. I loved it. And I now have singer Jim Croce’s earworm in my head.”

“Me, too.” She laughed.

“I love your descriptions in your prose. Right on the mark. Not too much, not too little.”

“Description can be hard.”

“But you do it so well. Any tips?”

“Well, I’ll tell you what I do. Two things. First, I see it in my head. I’m looking at the draft, and I say, ‘Hey, you know, there’s nothing here.’”

I laugh. “So, what do you do?”

“Well in Bad, Bad, Seymore Brown, the character with the problem is a college professor, a really nice woman, who teaches film, and her area of specialization is big Hollywood Studio films. When she was five, her parents were murdered. It was an arson murder, and she was lucky enough to jump out of the window of the house and save herself. So, Corie, who’s my detective, a former FBI agent, is called on, but not through herself, but through her dad, who’s a retired NYPD detective. He was a detective twenty years earlier, interviewing this little girl, April is her name, and they kept up a kind of birthday-card-Christmas-card relationship.”

“And the plot is great.”

“Thanks, but in terms of description, there was nothing there. But there were so many things to work with. So, after I get that structure, I see it in my head, and I begin to type it in.”

“The description?”

“Plot, then description.”

“And you mentioned another thing you do?”

“Research. And you don’t always have to physically go somewhere to do it. I had a great time with this novel. For example, it was during COVID, and nobody was holding a gun to my head and saying ‘Write’ so I had the leisure time to look at real estate in New Brunswick online, and I found the house with pictures that I knew April should live in, and that’s simply it. And I used that house because now April is being threatened, someone is trying to kill her twenty years after her parent’s death. Though the local cops are convinced it had nothing to do with her parents’ murder, but that’s why Corie’s dad and Corie get pulled into it.”

“So basically, when you do description, you get the structure, the bones of your plot, and then you go back and both imagine and research, at your leisure, the details that really set your writing off. What’s the hardest thing for you as a writer?”

“You know, I think there are all sorts of things that are hard for writers. For me, it’s plot. I’ll spend much more time on plot, you know, working it out, both from the detective’s point-of-view and the killer’s point-of-view, just so it seems whole, and it seems that what I write could have happened. For me, I don’t want somebody clapping their palm to their forehead and saying, ‘Oh, please!’ So that’s the hard thing for me.”

“You’ve talked with me about how focused you get when you’re writing.”

“Oh, yes. When you’re writing, you’re really concentrating. We were having work done on the house once and they were trying to do something in the basement, I forget what it was. But there was this jackhammer going, and I was upstairs working. It was when my kids were really young and, you know, I had only a limited amount of time to write every day, and so I was writing and I didn’t even hear the jackhammer until, I don’t know, the dog put her nose or snout on my knee and I stopped writing for a moment and said, ‘What is that?’ and then I heard it.”

“But it took your dog to bring you out of your zone. Not the jackhammer.”

“You get really involved.”

“Sort of transcending into another universe.”

“The story pulls you in. The weird thing is that I have ADD, ADHD, whatever they call it. I know that now, but I didn’t know that then, back when the jackhammer was in the basement. In fact, I didn’t know there was a name for it. I just thought, ‘This is how I am.’ You know, I go from one thing to the next. But people with ADHD can’t use that as an excuse not to write because you hyper-focus.”

“That’s interesting.”

“You don’t hear the jackhammers.”

“So things just flow.”

“Well, it’s always better in your head than on the page,” she says, “as far as writing goes.”

“I’d love to see your stories in your head, then, because your writing is great. As far as plotting, the book moves along at a fast clip. I noticed, distinctly, that your writing style is high with active verbs. Is that intentional or is that something that just comes naturally from you?”

“I think for me it just happens. It’s part of the plotting.”

“Well, it certainly moves the story forward.”

“Yes, I can see it would. But, no, I don’t think ‘let me think of an active verb’. You know,” she laughs, “I don’t think it ever occurred to me to even think of an active verb.”

“That’s funny. We’re all made so differently. I find it fascinating that, after all you’ve published, your Corie Geller novel is going to be part of the first series you’ve ever written. Everything else has been standalones.”

“Yes. I’m already writing the next book. Look, for forty-five years, I did mysteries. I did sagas. I did espionage novels. I did, you know, just regular books about people’s lives. But I never wrote a series because I was afraid I after writing one successful mystery, that I would be stuck, and I’d be writing, you know, my character and compromising positions with, Judith Singer goes Hawaiian in the 25th sequel. I didn’t want that. I wanted to try things out. So now that I’ve long been in my career this long, I thought I would really like to do a series because I want a family, another family.”

“Another family?”

“I mean, I have a great family. I have a husband who’s still practicing law. I have children, I have grandchildren, but I’m ready for another family.”

“And this series is going to be it?”

“It’s not just a one-book deal. I wanted more. So, I made Corie as rich and as complicated and as believable as she could be. It’s one thing to have a housewife detective. It’s another to have someone who lives in the suburbs, but who’s a pro. And she’s helped by her father, who was in the NYPD, who has a different kind of experience.”

“And that gives you a lot to work with. And, in an interesting way, at this stage of your life, another family to explore and live with.” I look at the clock. “Well, I guess we both need to get back to work.”

“This has been great. When you work alone all day, it’s nice to be able to just mouth off to someone.”

We both laughed and we hung up. It was a break in the day. But a good break. I think Susan fed her ADHD a bit with the distraction, but for me, I learned a few things in just the passing conversation. Writers are wonderful. If you haven’t done it today, don’t text, don’t email, but pick up the phone and call a writer friend you know. I hung up the phone with Susan, invigorated, ready to get back to work. As she said, it’s nice to be able to just mouth off to someone. As I would say, it’s nice to talk to someone and remember that, as writers, we are not alone, and we all have so much to learn.

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer and filmmaker and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. https://claystafford.com/

Susan Isaacs is the author of fourteen novels, including Bad, Bad Seymour Brown, Takes One to Know One, As Husbands Go, Long Time No See, Any Place I Hang My Hat, and Compromising Positions. A recipient of the Writers for Writers Award and the John Steinbeck Award, Isaacs is a former chairman of the board of Poets & Writers, and a past president of Mystery Writers of America. Her fiction has been translated into thirty languages. She lives on Long Island with her husband. https://www.susanisaacs.com/

Author Amulya Malladi on “Research: Doing It, Loving It, Using It, and Leaving It Out”

In this informal and delightful follow-up conversation with bestselling author Susan Isaacs, we chat about writing description, plotting mysteries, working with ADHD, and how building a fictional series can feel like creating a second family. A refreshing reminder of why writers write—and why conversations like this matter.

Amulya Malladi interviewed by Clay Stafford

“I’m talking today with international bestselling author Amulya Malladi about her latest book A Death in Denmark. What I think is fascinating is your sense of endurance. This book—research and writing—took you ten years to write.”

She laughs. “You know, it was COVID. We all didn’t have anything better to do. I was working for a Life Sciences Company, a diagnostic company, so I was very busy. But you know, outside of reading papers about COVID, this was the outlet. And so that’s sort of how long it took to get the book done. I had the idea for a long time. I needed a pandemic to convince me that I could write a mystery.”

“Which is interesting because you’d never written a mystery before. Having never worked in that genre, I’m sure there was a learning curve there for you.”

“A lot of research.”

“You love reading mysteries, so you already had a background in the structure of that, but what you’ve written in A Death in Denmark is a highly focused historical work. It’s the attention and knowledge of detail that really made the book jump for me. Unless you’re a history major with emphasis on the Holocaust and carrying all of that information around in your head, you’re going to have to find factual information somewhere. How did you do that?”

“Studies.”

“Studies?”

“You’ll need a lot of the studies that are available. Luckily, my husband’s doing a Ph.D. He has a student I.D., so I could download a lot of studies with it. Otherwise, I’d be paying for it. Also, I work in diagnostic companies. I read a lot of clinical studies. So these are all peer-reviewed papers that are based on historic research, and they are published, so that is a great source, a reference.”

“But what if you don’t have that access?”

“You can go to your library and get access to it as well. If you’re looking for that kind of historic research, this is the place to go.”

“Not the Internet? Or books, maybe?”

“Clinical studies and peer-reviewed papers, peer-reviewed clinical studies, they’re laborious.”

“And we’re talking, for this book, information directly related to the historical accuracy of the Holocaust and Denmark’s involvement in that history?”

“You have to read through a lot to get to it. And it’s not fiction. They’re just throwing the data out there. But it’s a good source, especially for writers because we need to know about two-hundred-percent to write five-percent.”

“The old Hemingway iceberg reference.”

“To feel comfortable writing that five, you need to know so much more. I could write actually a whole other book about everything that I learned at that time. And that is a good place to go. So I recommend going and doing, not just looking at, you know, Wikipedia, and all that good stuff, but actually going and looking at those papers.”

“Documents from that time period and documents covering that time period and the involvement of the various individuals and groups.”

“When you read a paper, you see like fifteen other sources for those papers, and then you can go into those sources and learn more.”

I laugh this time. “For me, research is like a series of rabbit holes that I find myself falling into. How do you know when to stop?”

“The way I was doing it is I research as I write, and I do it constantly. You know, simple things I’m writing, and I’m like, ‘Oh, he has to turn on this street. What street was that again? I can’t remember.’ I have Maps open constantly, and I know Copenhagen, the city, very well. But, you know, I’ll forget the street names. That sometimes takes work. I’m just writing the second book and I wanted Gabriel Præst, my main character and an ex-Copenhagen cop, to go into this café and it turned into a three-hour research session.”

“Okay. Sounds like a rabbit hole to me.”

“You’ve got to pull yourself out of that hole, because, literally, that was one paragraph, and I just spent three hours going into it. And now I know way too much about this café that I didn’t need to know about. Again, to write that five-percent, I needed to know two-hundred percent. I am curious. I like to know this. So suddenly, now I have that café on my list because we’re going to Copenhagen in a few weeks, and I’m like, ‘Oh, we need to go check that out.’”

“So you’re actually doing onsite research, as well?”

“Yes. I use it all. I think as you write you will see, ‘Okay, now I got all the information that I need.’

“And then you write. Research done?”

“No. I was editing and again I was like, ‘Is this really correct? Did I get this information correct? Let me go check again.’”

“Which is why, I guess, your writing rings so true.”

“I think it is healthy for writers to do that, especially if you’re going to write historical fiction or any kind of fiction that requires research. Here’s the important thing. I think with research, you have to kind of find the source always. You know? It’s tempting to just end up in Wikipedia because it’s easy. You get there. But you know, Wikipedia has done a pretty decent job of asking for sources, and I always go into the source. You know you can keep going in and find the truth. I read Exodus while I lived in India. One million years ago, I was a teenager, and I don’t know if you’ve read Leon Uris’s Exodus, but there’s this famous story in that book about the Danish King. When the Germans came, they said, ‘Oh, they’re going to ask the Jews to wear the Star of David,’ and the story goes, based on Exodus, that the king rode the streets with the Star of David. I thought that was an amazing story. That was my first introduction to Denmark, like hundreds of years before I met my husband, and that story stayed with me. And then I find out it’s not a true story. You know? You know, Marie Antoinette never said ‘Let them eat cake.’ And so it was like, ‘Oh.’”

“Washington did not chop down the cherry tree.”

“No, and the apple didn’t fall. I mean, it’s simple things we do that with, right? With Casablanca, it’s like you said, you know, ‘Play it again, Sam.’ And she never said that. She said, ‘Play it.’ And you realize these become part of the story.”

“Secondary sources then, if I get what you’re saying, are suspect.”

“Research helps you figure out, ‘Okay, that never happened.’”

“When you say that you’re writing, and you’re incorporating the research into your writing sometimes you can’t, you’re not in a spot where the research goes into it. So, how do you organize your research that you’re not immediately using?”

“I don’t do that. I’m sure there are people who do that well. I’m sure there are people who are more disciplined than I am. I’m barely able to block my life. I mean, it’s hard enough, so you know if I do some research, I know there are people who take notes. I have notes, but those are the basics. ‘Oh, this guy’s name is this, his wife is this, he’s this old, please don’t say he’s from this street, he’s living on this street…’ Some basics I’ll have, so I can go back and look. But a lot of the times I’m like, ‘What was this guy’s husband doing again?’ I have to go find it. I won’t read the notes in all honesty, even if I make them. So for me, it’s important to go in and look at that point.”

“And this is why you write and research at the same time.”

“And this is why maybe it’s not the best way to do the research. It takes longer, like I said, you spend three hours doing something that is not important, but hey, that was kind of fun for me. I was curious to remember about Dan Turéll’s books, because I hadn’t read them for a while.”

“Some writers don’t like research. You like research. And for historicals, there’s really no way around it, is there?”

“I take my time and I think I really like the research. I have fun doing it.”

“Does it hurt to leave some of the research out?”

“Oh, my God, yes. My editor said, ‘You know, Amulya, we need the World War II stuff more.’ I’m like, ‘Oh, really? Watch me.’ So I spend all this time and I basically wrote the book that my character, the dead politician, writes.”

“This is an integral part of the story, for those who haven’t read the book.”

“I wrote a large part of that book that she is supposed to have written and put it in this book. I put in footnotes.”

“Footnotes?”

“My editor calls me and she’s like, ‘I don’t think we can have footnotes and fiction.’ I’m like, ‘Really?’ And she goes, ‘You know, you can make a list of all of this and put it in the back of the book. We’ll be happy to do that. But you can’t have footnotes.’ I felt so bad taking it out because this was really good stuff. You know, these were important stories.”

“So it does hurt to leave these things out.”

“I did all kinds of research. I read the secret reports, the daily reports that the Germans wrote, because you can find pictures of that. I kind of went in and did all of that to kind of make this as authentic as possible, and then she said, ‘Could you please, like make it part of the book, and not as…’ She’s like ‘People are going to lose interest.’ So yeah, it does hurt. It really didn’t make me happy to do that.”

“You reference real companies, use real restaurants, use real clothing, use real drinks. You use real foods. Do you have some sort of legal counsel that has looked over this to make sure nobody is going to sue you for anything you write? Or how do you protect yourself in your research?”

“When I’m being not-so-nice about something, I am careful. I have not heard anything from legal. Maybe I should ask tomorrow. I think Robert B. Parker said this in an interview once: ‘If I’m going to say something bad about a restaurant, I make the name up.’”

“Circling back, you do onsite research, as well.”

“Oh, yeah. I’ve been to Berlin several times, so I know the streets of Berlin. I know this process. I know what they feel like. It’s easier to write about places you’ve been to, but the details you will forget. Even though I know Copenhagen very well, I still forget the details. ‘What is that place called again? What was that restaurant I used to go to?’ And then I have to go look in Maps, and find, ‘Ah, that’s what it’s called here. How do they spell this again?’ But I think, yes, from a research perspective, if you are wanting to set a whole set of books somewhere, and if you have a chance to go there, go. Unless you’re setting a book in Afghanistan, or you know, Iraq, then don’t go. Because I did set a book partly in Afghanistan and I remember I talked to a friend of mine. She’s a journalist for AP and she said, ‘Oh, you should come to Kabul.’ And I’m like, ‘No, I don’t think so, just tell me what you know so I can learn from that and write it.’ She’s like, ‘You’ll have a great time on it.’ And I said, ‘I will not have a great time. No, not doing that.’ But I think, yes…”

“When it comes to perceived safety, you’re like me, an armchair researcher. Right?”

“Give me a book. Give me a clinical study. Give me a peer-reviewed paper, I’ll be good.”

“What advice do you have for new writers?”

“Edit. Edit all the time. I’ve met writers, especially when they are new, they say things like, ‘Oh, my God! If I edit too much, it takes the essence away. I always say, ‘No, it just takes the garbage away.’ Edit. Edit, until you are so sick of that book. Because, trust me, when the book is finished and you read it, you’ll want to edit it again because you missed a few things. I tell everybody, ‘Edit, edit, edit. And don’t fall in love with anything you write while you’re writing it because you may have to delete it.’ You know, you may write one-hundred pages and realize, I went on the wrong track and now I have to go delete it.”

“And take out the footnotes.”

“Yeah, and take out the footnotes.”

Clay Stafford is a bestselling writer, filmmaker, literary theorist, and founder of Killer Nashville International Writers’ Conference. https://claystafford.com/

Clay’s book links: https://linktr.ee/claystafford

Amulya Malladi is the bestselling author of eight novels. Her books have been translated into several languages. She won a screenwriting award for her work on Ø (Island), a Danish series that aired on Amazon Prime Global and Studio Canal+. https://www.amulyamalladi.com/

Amulya’s book link: https://linktr.ee/amulyamalladi

Submit Your Writing to KN Magazine

Want to have your writing included in Killer Nashville Magazine?

Fill out our submission form and upload your writing here: